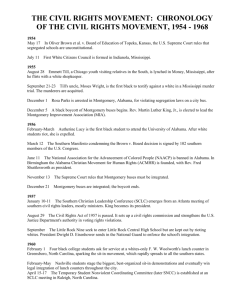

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

advertisement

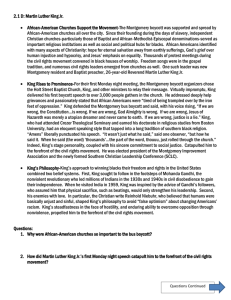

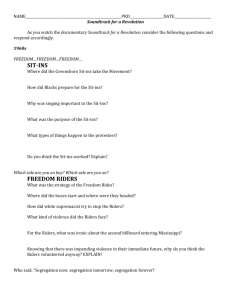

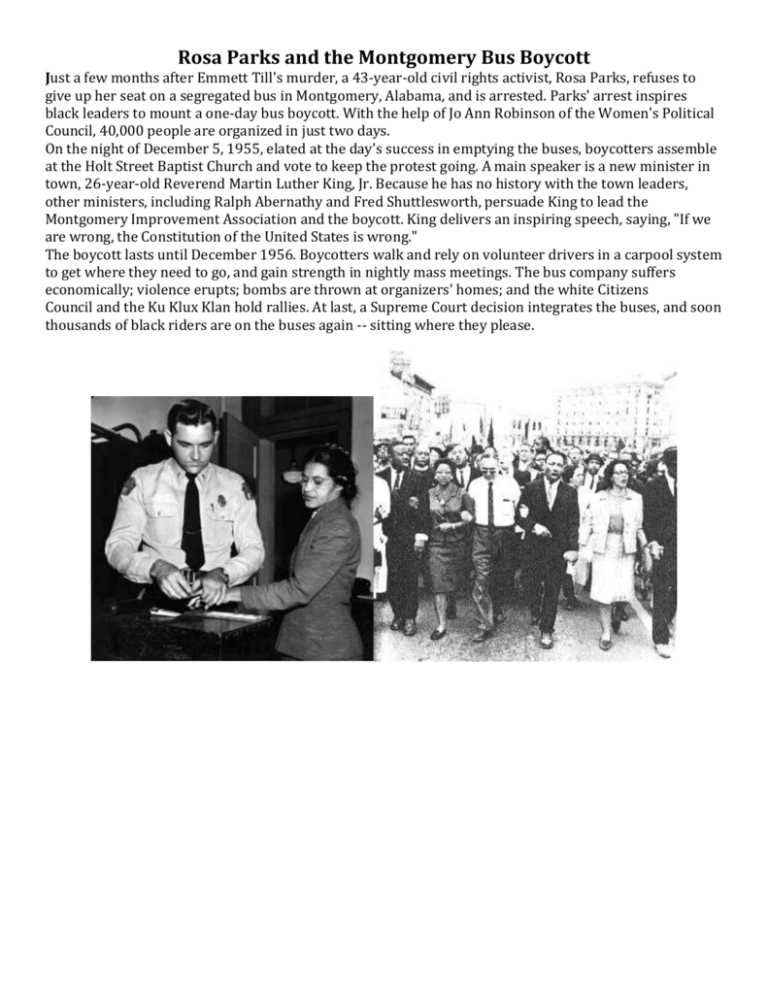

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott Just a few months after Emmett Till's murder, a 43-year-old civil rights activist, Rosa Parks, refuses to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama, and is arrested. Parks' arrest inspires black leaders to mount a one-day bus boycott. With the help of Jo Ann Robinson of the Women's Political Council, 40,000 people are organized in just two days. On the night of December 5, 1955, elated at the day's success in emptying the buses, boycotters assemble at the Holt Street Baptist Church and vote to keep the protest going. A main speaker is a new minister in town, 26-year-old Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. Because he has no history with the town leaders, other ministers, including Ralph Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth, persuade King to lead the Montgomery Improvement Association and the boycott. King delivers an inspiring speech, saying, "If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong." The boycott lasts until December 1956. Boycotters walk and rely on volunteer drivers in a carpool system to get where they need to go, and gain strength in nightly mass meetings. The bus company suffers economically; violence erupts; bombs are thrown at organizers' homes; and the white Citizens Council and the Ku Klux Klan hold rallies. At last, a Supreme Court decision integrates the buses, and soon thousands of black riders are on the buses again -- sitting where they please. The Sit-In Nonviolent Movement Southern cities maintain segregated public facilities -- like movie theaters, hotels, and lunch counters in downtown stores. In Greensboro, North Carolina, four black college students stage the first sit-in at a white lunch counter. Activist Jim Lawson holds workshops in non-violent protest at Nashville's Fisk University. He attracts people like college student Diane Nash and seminarians John Lewis and C. T. Vivian, and teaches non-violent direct action tactics adopted from Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi, including peaceful resistance. The protesters, dressed in their best clothes, target Nashville's lunch counters, where they sit and wait to be served. The stores respond by closing the counters, but the students continue to sit, quietly doing homework. After several weeks, their protest attracts gangs of white toughs, and police who arrest the activists for disorderly conduct. More students sit to take their places, filling the jails and refusing to pay fines. When punched or assaulted by segregationists, the protesters do not retaliate, but simply protect themselves and each other. The sit-in movement spreads to 69 cities across the South, black communities organize economic boycotts, and sympathetic Northerners picket local branches of the department stores. In Nashville, a climate of fear culminates in a bombing that destroys the house of Alexander Looby, a black lawyer who has been working with the activists. Thousands march to City Hall and confront Mayor Ben West. After the mayor concedes that the lunch counter segregation is wrong, businesses quickly desegregate. Elated with their success, students found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, working with Southern Christian Leadership Conference organizers like Ella Baker, who advises the students to maintain a separate organization. In the close presidential race of 1960, John Kennedy wins black support and, narrowly, the election. The Freedom Riders After the 1960 presidential election, civil rights activists pressure the Kennedy administration to support their cause and existing laws. The Supreme Court has banned segregation in interstate travel twice, but Southern states widely ignore the rulings. In May 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality sends mixed-race groups of non-violent volunteers, known as Freedom Riders, on bus trips into Dixie. They meet minor resistance in the upper South, but when they get to Alabama trouble erupts. Segregationists firebomb a bus in Anniston, Alabama, and Klan members attack the passengers as they disembark in Birmingham. Attorney General Robert Kennedy tries to protect the Riders, telling Governor John Patterson he will send Federal troops if the state can't maintain law and order. On the next leg of the trip, from Birmingham to Montgomery, the promised state police escorts evaporate. The Riders are assaulted and bloodied when they arrive in Martin Luther King's home town. As the violence rages, Kennedy calls in U.S. marshals, and ultimately Patterson is forced to dispatch the Alabama National Guard as well. When the riders continue into Mississippi under protection, they encounter heavy police presence and no violence -- but they are arrested in Jackson and sentenced to the maximum-security Parchman Penitentiary for trespassing. CORE sends more riders to the South to keep the protest going. Over the course of the next few months, 300 riders are arrested and sentenced in Mississippi. The activists find camaraderie in Parchman, singing freedom songs and providing mutual support. Ultimately, the Freedom Riders win their battle when Kennedy gets the Interstate Commerce Commission to ban segregation in interstate travel. The March On Washington Soon after the events in Birmingham, civil rights leaders announce plans for a mass march in Washington, D.C. to demonstrate for jobs and freedom. Attorney general Robert Kennedy, fearing more violence, is opposed to the plan. But long-time labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph, who first proposed such a march during Franklin Roosevelt's administration in 1941, and Bayard Rustin, organizer of the march's complex logistics, press ahead. On August 28, more than 200,000 people gather in peace and unity on the National Mall. Behind the scenes, SNCC leader John Lewis' speech causes conflict for its harsh words against the Kennedy administration and the nation's slowness to correct injustices. Persuaded by the 75-year-old Randolph to tone down the rhetoric, Lewis delivers an amended speech and few know of the controversy. The speech that will go down in the history books, however, is the one delivered by Martin Luther King as he stands before the Lincoln Memorial. "I have a dream," he declares, "that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character..." Though the March on Washington is a triumph, it comes with a tragic coda. Less than three weeks later, in Birmingham, the Ku Klux Klan bombs the 16th Street Baptist Church on a Sunday morning. Fifteen people are injured and four young girls are killed, filling many in the movement with rage. It will be 14 years before the first of three men, Robert Chambliss, is brought to justice in 1977; his companions Thomas Blanton, Jr. and Bobby Lee Cherry will not be convicted until 2001 and 2002, respectively. March from Selma to Montgomery On March 7, demonstrators start a 54-mile march in response to an activist's murder. They are protesting his death and the unfair state laws and local violence that keep African Americans from voting. Led by SNCC activists John Lewis and Hosea Williams, about 525 peaceful marchers are violently assaulted by state police near the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside Selma. Television networks broadcast the attacks of "Bloody Sunday" nationwide, creating outrage at the police, and sympathy for the marchers. Alabama police turn back a second march, led by Martin Luther King, Jr. and other religious leaders, on March 9th. Following a federal judicial review, the march is allowed to resume, escorted by the National Guard. On March 25, 25,000 marchers arrive at the State Capitol building in Montgomery. Soon afterward, the U.S. Congress will pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965, forcing states to end discriminatory voting practices. Freedom Summer In Mississippi, civil rights activists stage what many locals call an "invasion." Local NAACP leader Amzie Moore asks SNCC organizer Bob Moses to open offices in the state. Their program brings volunteers, including many white students from the North, to join local efforts at voter registration and education. Blacks had been denied access to the vote and intimidated in many ways. The state's political leadership, controlled by the segregationist Citizens Council, had been preventing blacks from registering to vote. The state had passed new voting laws to make registration even harder, and dependent upon local officials, who could register whites and reject blacks at will. In the state capital, Jackson, NAACP state field secretary Medgar Evers had organized a boycott of downtown stores. Hundreds of protesters were arrested in June 1963, with the mayor taking a hard line against them. Late on the night of June 11th, 1963, after President John F. Kennedy went on television asking Americans to support his civil rights bill, Evers was assassinated in his driveway. The murder weapon was traced to Citizens Council member Byron De La Beckwith, who would be tried twice and acquitted by all-white juries. (In 1994, when evidence emerged of improper trials, prosecutors would re-try Beckwith. Sentenced to life in prison by a mixed-race jury, he would die there in 2001.) Freedom Summer recruits train in Oxford, Ohio, and leave for Mississippi on June 20th, 1964. On the 21st, three organizers, all under age 25, disappear while investigating a church burning. The bodies of James Chaney, a black Mississippian, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, two white Northerners, will be found buried together on August 4th. Meanwhile, volunteers register voters for a new political party, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). Despite the tense climate, over 60,000 people join. In a presidential election year, the MFDP sends its own racially inclusive delegation to the Democratic National Convention, challenging the segregated delegation sent by the state's established Democrats. The nation watches a televised hearing on August 22 to determine which delegation will represent the state. The MFDP's Fannie Lou Hamer commands attention with an impassioned pitch for inclusion. But President Lyndon Johnson cuts off television coverage to end the divisive testimony and keep white Southerners in the party. In the end, the MFDP is not seated, but their presence and the moral strength of their argument impact national politics. The Nation of Islam, Malcolm X and the Black Power Movement The Nation of Islam, a religious organization, provokes controversy while promoting black pride and selfreliance. The group establishes local temples, teaches Muslim beliefs, creates black businesses and schools, and rehabilitates many convicts and former drug addicts. In 1963, Malcolm X becomes the group's national spokesman. His message of black pride, self-sufficiency, and self-defense stands in stark contrast to the Civil Rights Movement's non-violence. It also threatens whites. As Malcolm X becomes nationally known, his words inspire many blacks, but as he gains power, his relationship with the Nation of Islam deteriorates. In February 1965, members of the Nation of Islam assassinate him in Harlem. Malcolm X's philosophy survives, especially among younger civil rights workers. In 1965, Stokely Carmichael and SNCC mount a voter registration drive in Lowndes County, Alabama. In the 80% black county there are no black public officials, and blacks have been denied the vote. The group forms a new party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, and takes as its symbol a black panther. On May 3, 1966, the county's black residents vote for the first time since Reconstruction. Soon afterward, Stokely Carmichael takes over from John Lewis as SNCC's national chairman. The following month, James Meredith, who made plenty of enemies when he integrated the University of Mississippi in 1963, begins a solo March Against Fear through Tennessee and Mississippi. On the second day, he is shot and wounded. Civil rights leaders take up the march, and conflict emerges between Martin Luther King, who intends to proceed peacefully, and Stokely Carmichael, who would prefer to resist hostile state troopers. Partway through the march, to King's and many others' dismay, SNCC rallies crowds with a new slogan that will quickly take center stage: "Black Power!"