Shadowland Wales 3000-1500BC S Burrow

advertisement

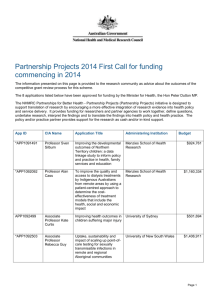

SHADOWLAND Wales 3000-1500BC BY S BURROW, Oxbow Books and Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, 2011, 192pp, 162 illus incl 122 col and 19 b/w plates, ISBN 978-1-84217-459-3, pb, £20 Hot on the heels of The Tomb Builders, a splendid production by the National Museum of Wales (Burrow 2006) comes a sequel by the same author. Written in an accessible style that carries the reader along and encourages one to complete the book at one sitting, this wellillustrated account of 3rd and 2nd millennium prehistory in Wales serves its purpose well and delivers a fresh and up to date interpretation of the period. It is a successful attempt at teasing out and elucidating detail of a time that the author describes as Shadowland, for it is contended that prehistory is full of shadows, or periods for which we have little evidence and none more so than between 3000 and 1500BC (calibrations not used to make it accessible). Perhaps we have a slightly better grasp of the latter part of that span because of the visible funerary monuments and practices that we encounter, but it is generally little characterised and certainly insufficiently recognised by the general public. Sandwiched between a horizon of extravagant monument construction during the early Neolithic and the widely recognised remains of the agricultural societies of the 1500s BC, this was a time when little is known of people or settlement. While ritual and ceremonial centres are present, until recently settlements and houses of the population have been missing and, on the face of it, there is little to characterise the shadows. However, the author supplements the meagre field evidence with information obtained from the artefacts that the ‘inhabitants left behind’ and allows this to build cumulatively to a body of evidence that helps fill the gap – and so the shadows are illuminated. Although divided into two parts, split at 2200BC that is, into what we would traditionally term the Later Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, the volume carefully avoids those categories so that we experience continuity rather than the disruption based on the technological divisions of old museum case labels. Instead the chronology is obtained from the available dated sites and is left to speak for itself without attempt to fit it into any preconceived or preexisting system. The volume is better for it and makes so much sense. Set against events on the world stage, Gilgamesh and Egyptian pyramid construction, along with changes that swept Europe in burial practice, the introduction of metal use and the widespread use of drinking pots or Beakers, Wales is seen very much as a backwater both in terms of world affairs and contemporary culture. Nevertheless there was enough going on to keep us intrigued. The features that emerge from the shadows begin with an arc of standing stones at Bryn Celli Ddu on Anglesey, all set around a post to highlight the alignment of midsummer sunrise. In southern England, the enclosure at Stonehenge was perhaps constructed at this time and while there may have been earlier stone arrangements, the sarsen horseshoe and other settings associated with the solar axis was not erected until perhaps half a millennium later. The similarity of enclosures at Llandegai A, Castell Bryn Gwyn Ysceifiog and several other Welsh sites with Stonehenge I is also noted and it may be that the potential influence of monuments in north Wales on elements of Stonehenge has largely been overlooked in the search for the origin of the bluestones in the Preseli Mountains. Here the Atlantic passage grave tradition is seen as an important influence in the use of circular architecture and accordingly the author notes a marked preference for the construction of circular mounds around 3000BC. The cremation cemetery at Stonehenge (Parker Pearson et al 2009) is matched by similar depositional practices at Llandegai A and Bryn Celli Ddu and in the repeated deposition of cremated remains and clearing out of the much smaller ring ditch at Sarn-y-bryn-caled. Rather than burial, this it is suggested, is a process of embedding the respective sites in cultural perception and traditions by marking them with the bones of the community. Continuity of this tradition of enclosure is represented at Llandegai by the construction of a henge of similar proportions to the earlier ‘formative’ henge. These are set a little over 100m apart although with a lack of evidence for burial it may be that the function had changed. One of the pits found within it contained a small stone plaque with Grooved ware style designs engraved on it, evidently similar affinities to the engraved chalk plaques found in a pit near Stonehenge (Harding 1988). The change in enclosure construction to the use of massive timbers rather than earthworks appears to be a key development during the 3 rd millennium. In England, such sites are exemplified by the West Kennet palisaded enclosures, in Scotland by Meldon Bridge and Forteviot; here, however, by those in the Walton Basin (Gibson 1999). The first, an arc of pits almost reaching across an interfluve between two brooks, with funnel arrangement or Avenue providing a formal entrance, if meant to enclose is an enormous affair. The second, the incomplete oval Hindwell enclosure, is even larger and took enormous quantities of timber to build. The purpose of both is obscure. With 8m high timbers, they were more than defensive and more about screening and obscuring. Burrow suggests that the Walton Basin is on a natural routeway that connected the lowlands around Oxford with the Welsh highlands and would have provided a perfect meeting place for separate communities. Maybe so, but elaborate display or ceremony with controlled visuals is also implied. The curious feature here is a funnel or Avenue as part of an entrance façade evidently formalising the approach as well as ultimate access. Burrow illustrates the Walton example alongside similar features at Meldon Bridge and Forteviot and it certainly stands out as an important component. Putting aside the strange antenna-like features, no such Avenue exists at the West Kennet enclosures, but there is of course an undated version in stone nearby that leads to the henge at Avebury. The Avenue at Stonehenge is rather different, defined by a simple bank and ditch and is similarly of uncertain date, but this and other versions in stone could easily have taken their cue from the funnel entrances of the palisaded enclosures. Attempt is made to approach the community through their round based Peterborough pots and by the quarrying activities at Graiglwyd on Penmaenmawr, Gwynedd (Williams et al 2011). The latter rock was widely disseminated across Britain and marked the commencement in North Wales of a tradition of extracting and working with rock that continued until much later with the quarrying of metal ore. But it is clear that dissemination was part of a two way process as large pieces of flint were being imported from the chalklands. More direct evidence of settlement is marked by the remains of two houses excavated at Trelystan, Long Mountain, with square hearths at their centre and constructed c2600BC. Components of these structures can be recognised from buildings at Durrington Walls, Wiltshire, Wyke Down, Dorset and recently, Marden, Wiltshire; the last currently interpreted as a sweat lodge. Whatever the function of the Telystan buildings, and they embraced a burial in a pit set between them, the architecture of the period is becoming more familiar. Pits were cut into the floor at the latter site, in one of which were fragments of Grooved ware pots and, although unstated, it may be that the flat-based pottery marks a move to the use of furniture. As is often the case such remains can be extremely fragile and easily be removed by cultivation and the point is made that pits containing Grooved ware elsewhere in Wales may mark the sites of vanished houses. Great emphasis is placed on the availability and use of copper, first as import and then as quarry. The flat axe from Merionshire described as one of the earliest metal finds in Wales utilised copper from Ross Island, across the Irish Sea in Co Kerry, but it wasn’t long before local ores were being used. Extraction may have been taking place at Alderley Edge around 2400 although there are uncertainties regarding the context of the radiocarbon date. Certainly copper was being quarried at Copa Hill before c2000cal BC. But the most extensive industrial complexes were at Paris Mountain, Anglesey, and the Great Orme, Conwy, where complexes of subterranean extraction tunnels remain. At the latter, some of them are so narrow that only children could have worked in them and with poor undoubted ventilation and light the conditions may have been little different from those of 19th century AD coal mines. Yet we are led to ask what drove the people to carry out the work on this kind of scale? Were the rewards sufficient? Or was this labour forced. Beakers finally hit Wales, but whereas the quarrying on Ross Island appears to be related to a Beaker settlement, the evidence here is of burials. Barrows and cemeteries discussed and there is much on death, grave goods and shift to cremation, but this is a reflection of the surviving evidence and the need to extract information from it. The story is one of ‘slow development of ancient themes’, of tradition and developing culture, but it is also of the place of Wales within a wider community. Development was certainly not insular and as the author observes, despite the influences of local geology and geography, most of the archaeological components are those that can be recognised right across the British Isles. An extensive list of recommendations for ‘further reading’ round off the volume, while the excellent illustrations bring the subject to life. In particular there is a superb aerial view of Penmaenmawr that places the site within topographical perspective, something very difficult to comprehend on the ground. The widespread availability of digital imagery perhaps produces a tendency to overuse the media and consequently, at least in my view, the distribution maps could have been much clearer (cf Grinsell 1972). A second personal niggle is the almost square format that publishers seem to love toying with from time to time evidently without a thought to the practical. Nevermind, it can sit alongside Briar Hill, Somerset Levels, and the other weird shapes on the book shelf, but in any case these are minor points and it is right that we explore the possibilities of illustration and presentation. This is good easy reading divided into attractive sub-chapters, perfect for the train or tube, but you will not want to put it down. Always engaging, the narrative hangs together extremely well and is consistently clear with concise description that deals well with awkward specialist concepts or pieces of jargon. It brings the subject up to date perfectly. References Burrow, S 2006 The Tomb Builders in Wales 4000-3000BC Cardiff: National Museum Wales Books Gibson, A 1999 The Walton Basin Project: excavation and survey in a prehistoric landscape 1993-7 CBA Research Report 118. York: Council for British Archaeology Grinsell, L V 1972 ‘Archaeological distribution maps’ in F Lynch and C Burgess (eds) Prehistoric man in Wales and the West, 5-18 Bath: Adams & Dart Harding, P 1988 ‘The chalk plaque pit, Amesbury’ Proceedings Prehistoric Society 54, 320-6 Williams, J Ll W, Kenney, J and Edmonds, M 2011 ‘Graig Lwyd (Group VII) assembages from Parc Bryn Cegin, Llandygai, Gwynedd, Wales’ in V Davis and M Edmonds (eds) Stone Axe Studies III, 261-278 Oxford: Oxbow Books Parker, Pearson, M, Chamberlain, A, Jay, M, Marshall, P, Pollard, J, Richards, C, Tilley, C and Welham, K 2009 ‘Who was buried at Stonehenge’ Antiquity 83, 23-39 David Field June 2012 “The views expressed in this review are not necessarily those of the Society or the Reviews Editor”