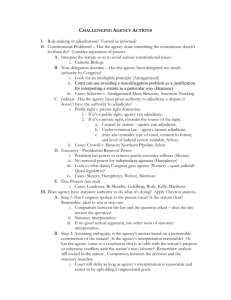

ADministrative Law Outline

advertisement