How might we tackle any differences in achievement?

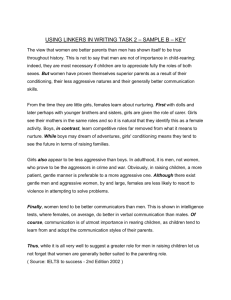

advertisement

Is there a gender gap? The nature of the relationship between gender and achievement is an area of concern for many teachers. But is the anxiety about the differences between boys’ and girls’ achievement misplaced? If there is a difference, how might teachers start to address it? Whilst there is not yet a great deal of strong evidence in this field (particularly that relating to post-16 education), a number of solid studies help us to answer these questions. What is the gender gap really like? The evidence shows a complex picture with some differences between male and female students’ achievement but also a great deal of variability between different subjects and different groups of students. A study1 which aimed to get a clear understanding of the nature of the gap scrutinised public examination results from KS1 to ‘A’ level. It found there were no significant differences in any subject between boys’ and girls’ achievement at the lowest grades and very little difference in their achievement in science and mathematics at any level. However, at higher levels of attainment in some subjects, a gap appeared and widened with each increasing level and grade. For example, in English male students did less well than females at KS2 and the gap widened at GCSE. But by ‘A’ level the gap had disappeared. The study did not find any differences in achievement in modern languages at ‘A’ level but did find that female students performed better than males in humanities and design-related subjects at ‘A’ level. Recent (2012) ‘A’ level results showed a narrowing of the gap between overall male and female performance with 26.1% of males achieving an A compared with 27.9% of females (the smallest percentage gap since 2001). A large international study2 found only very minor differences between male and female achievement. Gender differences were virtually zero in verbal ability; there were small differences in mathematics and very small differences in science. There was more variation within groups of males and within groups of females than there were differences between them. How might we tackle any differences in achievement? The author of the large international study3 argued that his evidence suggested that the difference between males and females should not be of major focus for teachers; the way to tackle differences in achievement is to focus on effective pedagogy for all students. This message is supported by other evidence. For example, a study4 which examined how effective different approaches were for 1 Gorard, S., Rees, G. & Salisbury, J. (2001) Investigating the patterns of differential attainment of boys and girls at school, British Educational Research Journal 27 (2) pp. 125-139 2 Hattie, J. (2009) Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses related to achievement, Routledge, London 3 Hattie, J. (2009) Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses related to achievement, Routledge, London 4 Younger, M & Warrington, M. et al. (2005) Raising boys’ achievement. London: DFES RR636 [online] Available at http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/5400/1/RR636.pdf This taster was created by CUREE for the TLRP. For further practitioner friendly resources, visit www.curee.co.uk closing the gender gap with school age students, found that there was no ‘silver bullets’- short term interventions did not work. But a number of strategies were found to be effective including: using mentoring sessions with students. These 15-30 minute sessions focused on planning homework and coursework, time management and revision techniques. Mentors directed the discussion, commenting positively about progress made and areas of weakness or difficulty. extending the range of teaching approaches used to engage as wide a range of students as possible. For example, including highly structured short- term tasks for lower-achieving male students. Interestingly mentoring has also been used to improve female as well as male achievement. In one college female second year students supported female first year A level science students5. What are the implications? College practitioners may like to consider: the evidence about differences between boys’ and girls’ achievement suggests a complex picture. You might want to investigate the nature of any gender difference in your classes. Do males or females outperform each other in homework, internal assessments, AS or A level results? Is there variation between different classes? You might also want to collect evidence about student perceptions ( e.g. through interviews or questionnaires) to supplement your achievement data. mentoring approaches were found to be an effective strategy for rising the achievement of male students. Could mentoring be used with some groups of students in your classes? The resources, ‘Using coaching and mentoring to support students’ and ‘Assertive mentoring’ give examples of how secondary and post-16 teachers have used mentoring with their students. What particular skills and attributes would you want the mentoring to focus on developing? extending the range of teaching approaches was a successful strategy. You might want to find out about the kinds of learning activities that your students prefer. For example, to what extent do they find group work, ICT and individual note-taking support their learning? Can you adapt your teaching to take account of both male and female preferences? The taster on this line’ Which learning activities do male and female students prefer?’ can be used to help you do this. 5 Ofsted (2011) Improving Science in Colleges This taster was created by CUREE for the TLRP. For further practitioner friendly resources, visit www.curee.co.uk