Curriculum - Rivers2Lake

advertisement

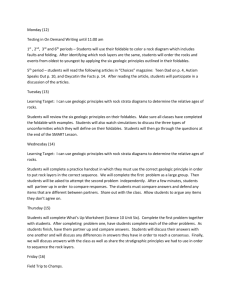

Unit Plan-Geology Introduction: This is a guide for a unit plan to teach students about rocks as a timeline, identifying rocks, using maps of Wisconsin's geology, and brownstone in Wisconsin. There are four other pieces to this: a bedrock map, a geologic past map, Geology map (for students to draw on), and "The Brownstone Times". This is added as other curriculum. Subject Areas: Science, Social Science / History Grade Levels: K-5 Great Lakes Literacy Principles: 2. Natural forces formed the Great Lakes; the lakes continue to shape the features of their watershed. 8. The Great Lakes are socially, economically, and environmentally significant to the region, the nation and the planet. Materials: Wisconsin’s Geologic Past page (one per student?) Clear jar or container Sand, giant rock, flat “skipping” rocks, chalk or white rock, soil (nutrient rich), and grass or tree debris Bedrock Geology of Wisconsin page (one per student?) Rocks to identify A way to project the picture below Copies of “Brownstone Times” Map of Wisconsin Brown, blue and green colored pencils Day one: Using rocks as a timeline Since students will have an understanding of the different types of rock and how they form, introduce the idea of using rocks as a timeline to explain what geological processes have happened in Wisconsin. Standards: Common Core, Performance Standards Grade 4 C.4.2 Use the science content being learned to ask questions, plan investigations, make observations, make predictions, and offer explanations E.4.1 Investigate that earth materials are composed of rocks and soils and correctly use the vocabulary for rocks, minerals, and soils during these investigations Introduction: As students enter the classroom, put them in partners or small groups and have them do the following: 1. Identify the rock (name) 2. Identify what type it is (metamorphic, igneous, sedimentary) 3. Give a hypothesis: where was this rock formed or how was it formed? Go around the room and have students answer the three questions above about their rock. Pass out the Bedrock Geology of Wisconsin. Now have students identify where their rock may have come from. Have them write down where they think their rock came from and one reason why they think that. Ask students to think about how old their rocks are. Are all of their rocks the same age? How do we know? We can age rocks using chemistry and we can use their “age” to make a timeline. Introduce an important geologic theory (taken from Wikipedia): “The Principle of Original Horizontality states that layers of sediment are originally deposited horizontally”. A better way of stating it: The Principle of Original Horizontality means that rock forms in horizontal layers because of gravity. To show this, pull out the clear jar or container. Place the large rock at the bottom of the jar (for igneous and metamorphic rock). (It may be helpful to have the Wisconsin’s geologic past page next to you to see how thick to make the layers. Students will look at the page after, but it could be more of distraction to hand them out right away). Explain that this is a bedrock layer, one of many that will be in the jar. Ask students how long it took to form this, explaining that this layer is far below them. This could have taken thousands of years to make and the layer represents rocks that are 2800 million years old! Next, pour sand (for sandstone) and explain that this layer is about 488-501 million years old. There is a missing layer between this layer and the layer beneath that was eroded away. What does it mean to be eroded? How does erosion happen? Pour chalk/white rock for dolostone/limestone. Add sand, another layer of chalk/white rock, and a few skipping stones (for shale). These layers are about 444-488 million years old. The next layer of chalk/white rock is 416-444 million years old. The layer above that is 359-416 years old and has shale above limestone. The next layer to be poured is the soil (glacial sediment). A very small layer of grass or tree debris represents the current soil that we can see and touch. Have students make observations about the layers. What do they notice? Are the layers mixed or separate? This is what is meant by original horizontality: the layers are on top of one another because of gravity. Now pass out the Wisconsin’s Geologic Past page to the students. Partner up students and assign them a “layer” (time period, such as Devonian or Silurian). Tomorrow they will research this time period. Close up by having them fill out an exit ticket that requires them to answer the following: 1. What geologic time period will you study? 2. How would you explain the Principle of Original Horizontality to a friend or family member? Day Two: Research and Teach about Geologic Formations Standards: Common Core, Performance Standards Grade 4 B.4.1 Use encyclopedias, source books, texts, computers, teachers, parents, other adults, journals, popular press, and various other sources, to help answer science-related questions and plan investigations C.4.1 Use the vocabulary of the unifying themes to ask questions about objects, organisms, and events being studied C.4.6 Communicate the results of their investigations in ways their audiences will understand by using charts, graphs, drawings, written descriptions, and various other means, to display their answers Today students will briefly research their time period they were assigned yesterday. Partners will make a poster that includes the following information: 1. Geologic Time Period Name 2. When it occurred (x-y million years ago) 3. What kind of geologic formations (types of rock) can be found in this time/layer? 4. What, if any, fossils can be found here? 5. Have at least two pictures of this formation or the fossils present (can be printed or drawn) When students are done, have them hang them up around the room. Have one partner stay with the poster while the other travels in a clockwise direction to another poster. Use the gallery approach to have students interact about the information. The poster presenter should inform the other student about what they learned. Continue rotating students every minute or so until they return to their own poster. Now have the partner that presented rotate. Have students fill out an exit slip: 1. What was one new thing you learned? 2. What else would you like to learn? Day Three: Local Geologic/Rock Formation: Brownstone Students will learn what brownstone is, where it is located, and why it was important to this area. Standards: Common Core, Performance Standards Grade 4 B.4.3 Show* how the major developments of scientific knowledge in the earth and space, life and environmental, and physical sciences have changed over time As students walk into the classroom, have them take out a sheet of paper. Display the following picture for students to see (can be found at this link: http://wisconsinhistoricalmarkers.blogspot.com/2013/06/port-wing-brown-stone.html): Have students answer the following: 1. Have you seen this before and, if so, where? 2. What do you think the bricks are made of? 3. Where did the bricks come from? 4. Have you seen rock like this before? Where? This is a historical marker found in Port Wing, WI. The bricks are made of brownstone that came from this region. If you go to Bayfield around the Apostle Islands, you can see outcrops (areas where the bedrock can be seen above ground) of brownstone. Give students a copy of “Brownstone Times” (Information from http://wisconsinhistoricalmarkers.blogspot.com/2013/06/port-wing-brownstone.html and https://web.archive.org/web/20060813181044/http:/www.nps.gov/apis/quarries.htm ) Have them write down or highlight/underline the following: 1. Who (or what) is this article about? 2. Where is brownstone found? 3. When did quarrying (moving brownstone) start in the Apostle Islands? In Port Wing? 4. Why was brownstone important (think about what happened in Chicago in 1871)? 5. What caused quarrying to stop? Put students into groups to discuss the answers to the questions above. Then pass out maps of Wisconsin and have them draw the following: 1. Mark each place the article listed with a dot to show where brownstone quarries are. 2. Connect the dots. This is roughly where the brownstone exists. 3. Color the brownstone area with brown. 4. Color Lake Superior with blue. 5. Color the rest of Wisconsin with green. This map is the one they should mark and color. The other two are just to show where in Wisconsin this is and also to give them the names of the islands.