country epidemic sub..

advertisement

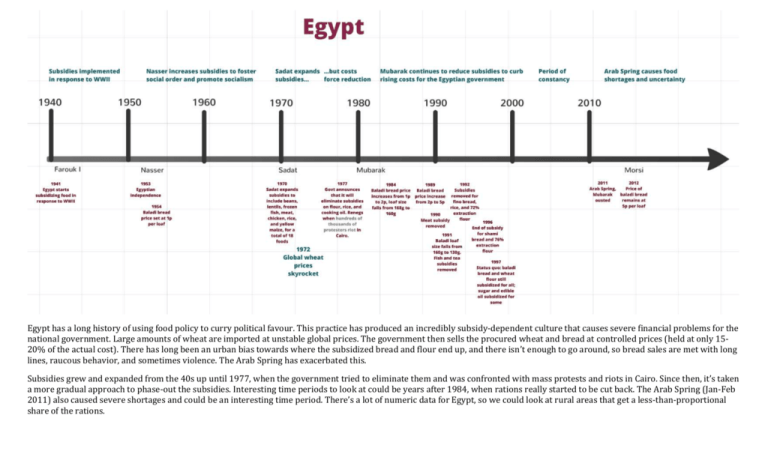

Egypt has a long history of using food policy to curry political favour. This practice has produced an incredibly subsidy-dependent culture that causes severe financial problems for the national government. Large amounts of wheat are imported at unstable global prices. The government then sells the procured wheat and bread at controlled prices (held at only 1520% of the actual cost). There has long been an urban bias towards where the subsidized bread and flour end up, and there isn’t enough to go around, so bread sales are met with long lines, raucous behavior, and sometimes violence. The Arab Spring has exacerbated this. Subsidies grew and expanded from the 40s up until 1977, when the government tried to eliminate them and was confronted with mass protests and riots in Cairo. Since then, it’s taken a more gradual approach to phase-out the subsidies. Interesting time periods to look at could be years after 1984, when rations really started to be cut back. The Arab Spring (Jan-Feb 2011) also caused severe shortages and could be an interesting time period. There’s a lot of numeric data for Egypt, so we could look at rural areas that get a less-than-proportional share of the rations. India’s food subsidies are largely centered on domestic food production and distribution. The government sets minimum support prices (MSP) at which is procures rice and wheat from different regions. The government also sets a central issue price (CIP) at which the food grains are sold. CIPs vary by income group – there is a separate price for those above the poverty line (APL), below the poverty line (BPL), or the poorest of the poor (AAY, or Antyodaya Anna Yojna). This tiered system was introduced in 1997, with AAY added in 2000. CIPs fluctuated in the 90s but have been held constant since 2002. I have extensive data for prices, regionality, estimated caloric increase from subsidies, etc, that we can look at if need be. I’ve charted the CPI fluctuations from 1982 onwards in case that’s useful for situating epidemics in context – the spike in 1999 and 2000 could be a really interesting time period to investigate. (Not that I didn’t adjust the data for inflation – partly because we’d be looking at short-term fluctuations) Half of Bangladesh’s 150M citizens live below the national poverty line. Rural poverty is proportionally much higher than urban, partly because about half of the rural population is landless, depending on seasonal agriculture for employment. During the off-season, from January to June, about a third of the rural workforce experiences under- and un-employment. Bangladeshi history is marked with foreign control, famines, floods, and other hindrances to development that have exacerbated poverty. The food ration system in Bangladesh has historically been skewed towards public employees (particularly police and military servicemen) and urban areas. This emphasis decreased in the 1970s, when many rural poverty measures were introduced, but the problem remains to this day. Many of Bangladesh’s food subsidy strategies are conditional food transfers. Post-famine and post-flood time periods would be particularly good for investigating epidemics. The Philippines’ National Food Authority (NFA) subsidizes rice, which is sold to consumers through accredited retailers at a mandated, below-market price. Quantities are not restricted. NFA rice is widely perceived to be of poor quality. In 2006, a study showed that only 16% of the population purchased the subsidized rice. Subsidies are import-dependent. Distribution is a key problem; only 25% of poor participate in the subsidies; 48% of beneficiaries are non-poor. The subsidy program expanded and then contracted in the 1980s. There is currently a political movement to eliminate the NFA, though individual-based targeting is being investigated in the Manila metro area.