Document E-African Community

African Community-Background

The area around Collect Pond was also home to a large African American community since the 17th century. African-Americans inhabited the area that would later become Five

Points on and off from the mid-seventeenth century onward. African Americans were granted the land conditionally-under the half-freedom system, Africans had to work part of the year in return for some land. When New Netherlands came under British rule, they had to give up the land they farmed. Since parts of the area were less suitable for farming than others and, African Americans were given undesirable pieces of land.

After slavery was abolished in New York, early in the nineteenth century, slaves who had been agricultural laborers along the Hudson Valley and on Long Island tended to migrate to

Manhattan and many came to the area around Collect Pond where black freemen had made their homes. By the time Collect Pond was drained and filled in, these freemen and freed slaves had come to be the most common as well as longest-term residents. As impoverished immigrants began to arrive in increasing numbers, the African Americans achieved a slight economic advantage over their immigrant neighbors so by running grocery-grog shops, taverns, oyster-bars, and — most notably — dance halls.

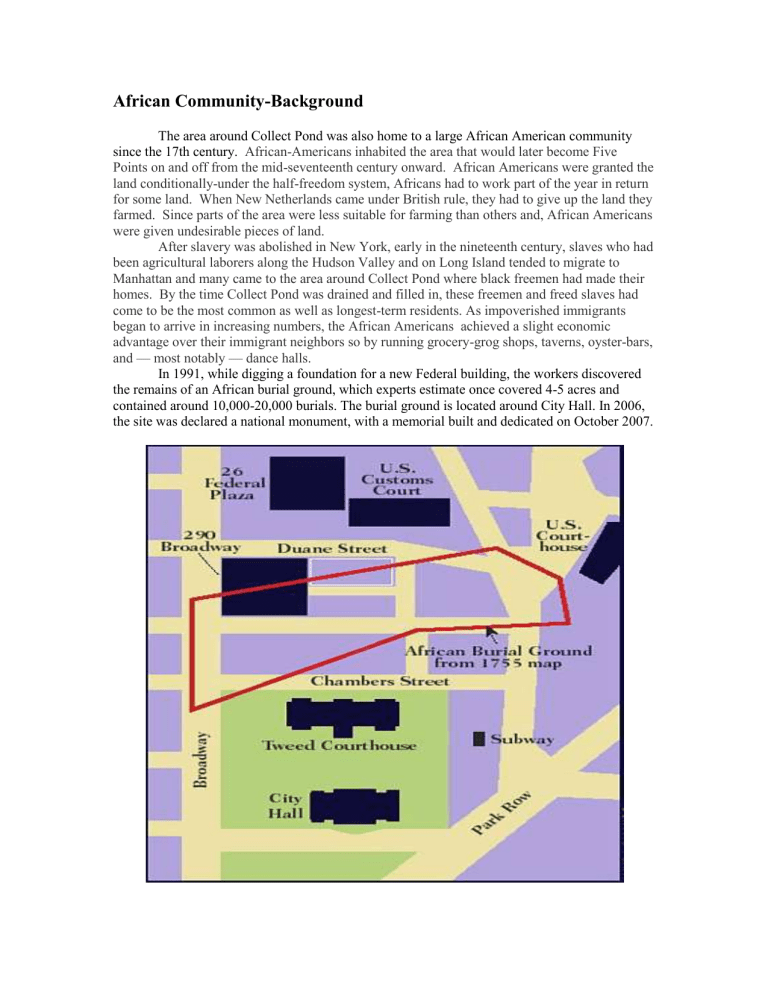

In 1991, while digging a foundation for a new Federal building, the workers discovered the remains of an African burial ground, which experts estimate once covered 4-5 acres and contained around 10,000-20,000 burials. The burial ground is located around City Hall. In 2006, the site was declared a national monument, with a memorial built and dedicated on October 2007.

Artifact E-1) Pendant, silver.

Source: African Burial Ground; From Burial 254, Catalog # 1243-B.001

This is a piece of adornment (jewelry) from the African Burial Site in lower

Manhattan. Personal adornments (jewelry) like those found at the African Burial Ground were easy to transport and widely available, esp. in North America. Most, if not all, were available in New York City as well. It is made of cast silver. The upper portion has a slightly twisted metal hoop. A jump ring is attached to the bottom of the sphere, from which hangs a pear-shaped dangle.

This piece of adornment is different from other pieces in European trading posts and Native American encampments from the 18 th

century. This is not because of trade in silver. From the 1750’s to the 1830’s, silver jewelry went hand in hand with the fur trade in upstate New York and in the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi regions. Fur from the north and the west passed through colonial Manhattan; silver ornaments (decorations and jewelry) made by city artisans followed the same routes taken by the traders of animal skins. The pendant may have been made with the general customer in mind. Its pear shape was a perennial favorite among colonial American jewelry wearer

Artifact E-2): Beads, Bead Type 2, diameters 4.8-7.3 mm.

Source: African Burial Ground; From Burial 254, Catalog # 1243-B.001

If you examine the trade between Europe and Africa, you will notice that glass beads formed the largest portion of personal decorations imported to western Africa, with “many billions landed in barrels, cases, and casks” along the Guinea Coast. Many European countries had their own glass bead industries; Venice was the main center of European bead production, though bead making also thrived in the Netherlands from the late 16 mid 18 th th through the centuries. However, many African countries added to or even melted down

European beads to make their own versions. These beads look more like African designs and work than European. The presence in colonial Manhattan of glass beads that look more like

West African beads tells us that the movement of adornment (jewelry) was from Africa to the

Americas. This fact about the trade in Africans is not well known. Africans crossed the

Atlantic as sailors on ships, not just as enslaved labor chained below deck. The presence of enslaved and free black sailors in North American ports increased steadily after 1740, as did the number of black New Yorkers who fled from bondage.

Personal adornment was sold almost anywhere. The account books of merchant

Samuel Deall record necklaces, earrings, and beads sold in 1758. The price of a “bunch” of black beads, perhaps like those shown below, was 2 shillings and sixpence. Deall’s store on

Broad Street was typical of its time, stocking clothing, foodstuffs, house wares, light construction materials, and “all elements of ornamentation for person and home.” Although

Africans are not likely to have shopped at stores like Deall’s, some of the less expensive adornments merchants and craftsmen carried would have made their way into smaller retail venues. “Cheap sales” and auctions of over-stocked merchandise lowered retail prices, and small-scale vendors such as peddlers would have bought inexpensively and sold with a modest mark-up.