Syntax - Haiku Learning

advertisement

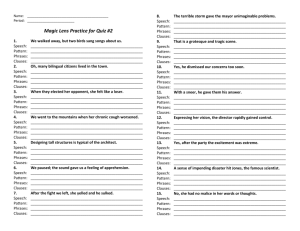

Syntax Adapted from A Guide for Advanced Placement English Vertical Teams. New York: The College Board Syntax, or sentence structure, should not be studied in isolation, but in conjunction with other stylistic techniques that work together to develop meaning (see other elements of style analysis we’ve studied). Analysis of style and meaning never relies on one concept alone. You can analyze sentence structure in several ways: 1. Examine sentence length: telegraphic (less than 5 words), short (5-8 words), medium (15-20 words), or long and involved (30 words or more). Does the sentence length fit the subject matter? What variety is present? Why is the length effective? 2. Examine sentence beginnings. Variety? Pattern? 3. Examine the arrangement of ideas in a sentence. Is purpose evident? 4. Examine the arrangement of ideas in a paragraph. Evidence of pattern or structure? 5. Examine sentence patterns: Declarative sentence: makes a statement (The king is sick.) Imperative sentence: gives a command (Stand up.) Interrogative sentence: asks a question (Is the king sick?) Exclamatory sentence: makes an exclamation (The king is dead!) Simple sentence: one subject and one verb (Ms. Jackson smiled at her adoring class.) Compound sentence: two independent clauses joined by a coordinate conjunction (and, but, or) or by a semicolon (Ms. Jackson smiled at her adoring class, and they held out their excellent essays to her.) Complex sentence: independent clause and one or more subordinate clauses (She said that she would always remember them.) Compound-complex sentence: two or more principal clauses and one or more subordinate clauses (Ms. Jackson smiled while her adoring students raised their hands, and she wanted to give all of them a chance to share their brilliant thoughts.) Loose sentence: makes complete sense if brought to a close before the actual ending (We reached Saigon/ that morning/ after a turbulent flight/ and three mediocre movies. Periodic sentence: has a series of modifying phrases inserted in the sentence and makes sense only when the end is reached (That morning, after a turbulent flight and three mediocre movies, we reached Saigon). Balanced sentence: phrases or clauses balance each other by virtue of their likeness of structure, meaning or length (He maketh me to lie down in green pastures; he leadeth me beside still waters.) Natural order: subject before predicate (Pho is eaten in Saigon.) Inverted order: predicate before subject (In Saigon is eaten pho.) Normal sentence patterns are reversed to create emphatic or rhythmic effect Split order: predicate divided into two parts with subject in middle (In Saigon, pho is eaten.) Juxtaposition: poetic and rhetorical device in which normally unassociated ideas, words, or phrases are placed next to one another, creating an effect of surprise and wit (“The apparition of these faces in the crowd;/Petals on a wet, black bough.” Ezra Pound, “In a Station of the Metro”) Parallel structure/parallelism: grammatical or structural similarity between sentences or parts of a sentence. Words, phrases, sentences and paragraphs are arranged so that elements of equal importance are equally developed and similarly phrased (She was eating, drinking, and sleeping English 10.) Repetition: words, sounds, or ideas are used more than once to enhance rhythm and create emphasis (“government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth” Abraham Lincoln, “Gettysburg Address”) Rhetorical question: expects no answer, used to draw attention to a point, generally stronger than a direct statement (If Mrs. Jackson loves us so much, why did she leave us?)