jbi12553-sup-0001

advertisement

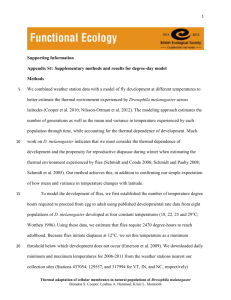

Journal of Biogeography SUPPORTING INFORMATION Latitudinal shift in thermal niche breadth results from relaxed selection on heat tolerance during a climate-mediated range expansion Lesley T. Lancaster, Rachael Y. Dudaniec, Bengt Hansson and Erik I. Svensson Appendix S1 Supplementary methods. Additional information on sampling methods We collected wild-caught, adult, individual Ischnura elegans from Swedish populations for thermal tolerance experiments in June–early August 2012 and June–late July 2013. In 2012 we captured individuals from 15 populations in southern Sweden (mean latitude 55.73°, SD 0.22°), which is representative of the northern part of the species’ core ancestral range (hereafter the core region). In 2013, we captured adult individuals from 11 populations at the leading edge of the species’ range in central Sweden (hereafter the edge region; mean latitude 59.61°, SD 0.15°). We aimed to match the core and edge regions for the distance between populations and the location of each study region in reference to the coastline, in order to minimize non-climatic habitat differences between regions (Fig. 1 in main text). In both core and edge regions, individuals were captured using butterfly nets between 09:00 h and 13:00 h, during which time we visited multiple populations on each day. Individuals were collected from the shorelines of large ponds and lakes, characterized by low, patchy, often disturbed, vegetation, and shallow, sandy, reed beds. Thus microclimatic variation and opportunities to thermoregulate behaviourally were similar in both regions, although unmeasured differences in biotic interactions and microclimates between regions may underpin some aspects of thermal-tolerance evolution and range expansion that were beyond the scope of this study (Sears et al., 2011). Captured individuals were then transported to Lund University in Skåne (core region) or the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences’ Grimsö Field Station in Västmanland (edge region) for thermal experiments. In transit, the damselflies were kept cool in mesh cages and provided with moistened cotton wool as a water source. In total, we sampled damselflies on 61 unique days covering the adult flying season, from 31 May to 3 August in 2012 and from 18 June to 27 July in 2013. Near-daily trials ensured adequate sample sizes for each population and spread sampling across the entire adult flying season in each region (Fig. S1). Core populations were sampled primarily in 2012, and edge populations were sampled only in 2013. We repeat-sampled nine of the 15 core populations in 2013 and compared those individuals’ thermal tolerances to tolerances of individuals sampled over the equivalent time period in 2012, to estimate any possible yearly variation in physiological tolerances that could compromise our interpretations. In a cox proportional hazard model, the effect of year (2012 versus 2013) on cold-tolerance phenotypes in core populations was 0.016 ± 0.24 SE (z = 0.07, P = 0.95) and the effect of year (2012 versus 2013) on heat-tolerance phenotypes in core populations was 0.001 ± 0.25 (z = 0, P = 1). Although it was not feasible to estimate yearly variation in thermal tolerance within the edge region, we concluded that, at least in the core, 2013 was no different from 2012 in damselfly thermal tolerances, and thus phenotypes were directly comparable across years. Similarly, any yearly variation in weather patterns during our sampling interval could have affected our results regarding the effects of recent weather on thermal tolerance plasticity. Within both core and edge regions, however, daily temperature patterns during the sampling interval were highly congruent across years: maximum, mean and minimum temperatures for Eskilstuna (edge region) were 29, 17, 7 °C in July 2013 versus 27, 17, 6 °C in July 2012, and for Malmö (core region) 29, 18, 8 °C versus 27, 16, 9 °C; data from the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute, http://www.smhi.se. Thus although edge populations were only sampled in 2013, recent weather events experienced by those individuals in 2013 were similar to conditions they would have experienced if they had been captured in 2012, the same year in which most of the thermal trials were conducted in core populations. Additional information on thermal trial methods During both heat- and cold-ramping trials, damselflies were held in individual enclosures and provided with ventilation and cotton wool soaked in water, to prevent the confounding effects of asphyxiation and dehydration. The final temperatures of 2 °C (lower tolerance) and 43 °C (upper tolerance) were established during pilot studies as those at which approximately 50% of the individuals were knocked down (i.e. no longer standing). These temperatures are similar to recorded temperature extremes in southern and central Sweden (http://www.smhi.se). Experimental temperatures were validated using iButton data loggers (Maxim Integrated, San Jose, CA, USA) placed in individual containers and distributed throughout the thermal chamber during trials. Overnight cold-ramping trials typically lasted 16 h (± an SD of 1.5 h), and cold-ramping trial duration had no effect on cold-tolerance phenotypes (effect = 0.006 ± 0.03, z = 0.22, P = 0.83). Additional information on weather station data We used the Eskilstuna weather station for edge populations, located 16–84 km from the study sites (mean distance = 50 km). For core populations, we used data from the Malmö weather station, 9–110 km from the study sites (mean distance = 29 km). Weather data were provided by the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute, http://www.smhi.se. Data from these stations collected in 2012 and 2013 were used in our analyses of effects of recent weather events on adult damselfly thermal tolerances, and to compare regional weather variation among years (see above). REFERENCES Sears, M.W., Raskin, E. & Angilletta, M.J. (2011) The world is not flat: defining relevant thermal landscapes in the context of climate change. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 51, 666–675. Daily temperatures on capture and non-capture dates (a) 20 15 A 10 160 170 edge populations core populations 12 7-day temperature minimum (° C) Daily mean temperatures (° C) edge populations core populations 150 Variation in 7-day temperature minima experienced by captured individuals (b) 180 190 200 capture date (day of year) 210 10 8 6 B 4 150 160 170 180 190 200 210 capture date (day of year) Figure S1 Weather variation in core and edge regions during the sampling interval. (a) Daily temperatures during the field season on capture dates (black symbols) and non-capture dates (grey symbols). Capture dates spanned the peak flight season for Swedish I. elegans, and experiments were terminated when adult individuals could no longer be captured in sufficient numbers for thermal trials. (b) Variation in weekly minimum temperatures experienced by captured individuals from core versus edge regions.