633-1766-1-PB

advertisement

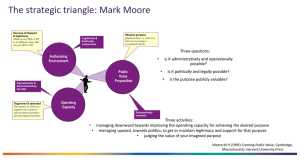

Research Abstract: Technical Innovation, Scientific Productivity, And Dimensions of Power Andrea Deyanira Beattie andrea.beattie@tamiu.edu (Texas A&M International University) Marcus Antonius Ynalvez mynalvez@tamiu.edu (Texas A&M International University) Introduction: Scientific laboratories, the social setting wherein the process of knowledge production and innovation typically occur, are subject to variances in power among actors working in these production sites. Thus, we focus on the relationship among power, scientific activities, and technical outcomes, on the one hand, and scientific productivity and technical innovation, on the other, to gain a fundamental understanding of the dimensionalities of power in the laboratory setting. Although the role of power in the scientific laboratory has been studied before (Doing 2004, Epstein 2008, Hong 2008), it has often taken a qualitative point of view and none of the extant studies have ever systematically teased out the various dimensionalities of power. Hence, in order to understand the role of power in scientific laboratories, defined by Weber as carrying out your will without resistance (Uphoff 1989), this paper proposes to explore the relationship between personal and contextual dimensions as they relate to scientific productivity and innovation by (1) operationalizing power by breaking the concept down into its individual dimensions including: personal attributes, political power (authority), moral power (legitimacy), social power (social status), and informational power and (2) measuring publication productivity using an ADB Productivity Index that takes into account both quantitative and qualitative aspects. With its success, this paper has the implications of offering a uniform measure for publication productivity that can be adopted in future studies on scientific productivity and innovation as well as shed some light on the variances of power in the scientific laboratory setting. Theoretical Framework: As shown on Figure 1, the model for this paper borrows from the works of Turner (2005) and Uphoff (1989) in identifying the directionality of power and its key dimensions. Through our literature review, we identify common themes and isolated the dimensions recognized as the most influential in the scientific process. Then, we tested the relationship between our independent variables, which include personal attributes, political power (authority), moral power (legitimacy), social power (social status), and informational power, and our dependent variables, which include publication productivity, manifested in the ADB Productivity Index, and technical innovation. Hypothesis-Driven Question: The purpose for breaking down power into its conceptual dimensions is to isolate them into more manageable components and recognize those most relevant in today’s contemporary scientific production system. Ultimately, this paper proposes to answer the following research question: How do the components of political power, moral power, social power, and informational power influence levels of scientific productivity and technical innovation? Data and Methods: In 2009-2010, we interviewed a random sample of n=294 molecular biological scientists in national universities and research institutes in Japan (n=100), Singapore (n=94), and Taiwan (n=100). Among the scientists sampled for the face-to-face quantitative survey, the group was stratified into professors (n=30) and graduate students (n=70) per individual country. Scientists were chosen from these three locations as Japan, Singapore, and Taiwan are the highest ranking countries in scientific productivity in East Asia. Top universities from each location were chosen for the study as these scientists are the most likely to show patterns of international collaboration, diverse networks, and high levels of scientific productivity. In order to achieve a meaningful description of the dimensions of power in the laboratory setting, we applied a micro-level analysis as recommended by Collins (2000). For examining power, a microsituational phenomenon, we utilized the day-to-day activities of scientists. Thus, the laboratory is the level of analysis and the scientist is the main unit of analysis. This paper hopes to discover valuable findings regarding interaction among scientists and the dynamics of power in the scientific laboratory. We applied a series of one-way analyses of variance as well as nominal error linear regression modeling. Measures for our independent variables included personal attributes (such as country, gender, marital status, parenting, etc.); political power, or authority; moral power, or legitimacy, social power, or social status; and informational power. Our main dependent variable, scientific productivity, included the ADB Productivity Index, a rough measure for publication productivity that gives top journals a weight of 3 and non-top journals a weight of 1 to measure both quantitative and qualitative aspects. Technical innovation was measured through self-reported number of patents generated. Findings and Conclusion: Results using the ADB productivity index indicate that dimensions of power having do with authority, social status, and use of Internet are significantly associated with productivity, but legitimacy displayed no significant relationship with productivity in scientific laboratories. Our results reveal that there is a distinction between authority and legitimacy, but there is a need to reassess this distinction using quantitative methods. We hope that by breaking power down into more manageable components, we may be able to gain a better understanding of power relationships as they affect productivity in sciences. References: Collins, R. (2000) Situational Stratification: A Micro-Macro Theory of Inequality. Sociological Theory, 18(1): 17-43. Doing, P. (2004) Lab hands and the Scarlet-O: Epistemic Politics and Scientific Labor. Social Studies of Science, 34(3): 299-323. Epstein, S. (2008) Culture and Science/Technology: Rethinking Knowledge, Power, Materiality, and Nature. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Hong, W. (2008) Domination in a Scientific Field: Capital Struggle in a Chinese Isotope Lab. Social Studies of Science, 38:543. Turner, J. (2005) Explaining the Nature of Power: A Three-Process Theory. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35: 1-22. Uphoff, N. (1989) Distinguishing Power, Authority, and Legitimacy: Taking Max Weber and His Words by Using Resource-Exchange Analysis. Polity, 22(2): 295-322.