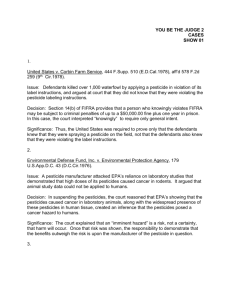

Opposition to Motion to Dismiss

advertisement