Introduction - Scholars at Princeton

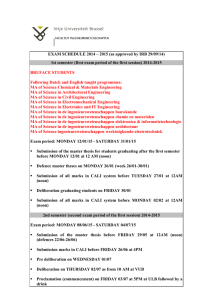

advertisement