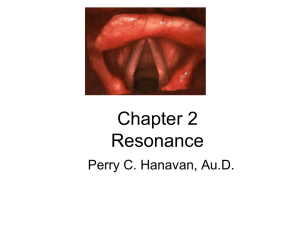

PAS 6 Program - Physiology and Acoustics of Singing

advertisement