Charles Barzun, University of Virginia, Law School

advertisement

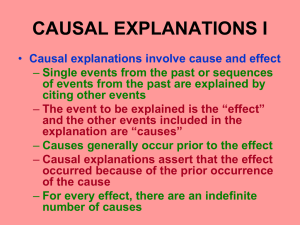

Why it Matters what Matters: Causation and Legal Doctrine Charles L. Barzun I gather from my exchanges with Jack that at least one hope for this conference is that we might say something provocative about how the tools of intellectual history might be used for understanding the four topics considered. What follows, therefore, is an effort to provoke, which it does in two ways: first, by criticizing what I perceive (perhaps wrongly) to be a trend in legal history, and second, to level that criticism from an unabashedly “presentist” perspective. The trend to which I refer is historians’ dwindling interest in making causal claims about events of the past. My claim is that giving up on causal claims about, in particular, why past court decisions were made threatens to undermine one of the most potentially useful ways in which history could be relevant to the concerns of judges and lawyers tasked with interpreting legal doctrine. I will first explain the kind of use of history I mean and then explain why giving up on causal explanations would limit that use. Let me begin by stating a thesis, which I think is true, but which I will only partially defend here: Historical evidence indicating that a particular judicial decision was decided for reasons unrelated to the legal considerations relevant to the issue at hand undermines – or “impeaches” – that decision’s status as binding precedent. I will call this the Impeaching Thesis because it makes a claim about what it takes to “impeach” a court precedent or (put another way) to erode its legal 1 authority. Of course, it is a controversial question what the “legal considerations” in the Impeaching Thesis properly include. Do they include, for instance, the social, political, or economic consequences of the decision? Thankfully, we can bracket that question for now. We need only assume that there are some factors that are properly relevant to a court’s decision, and others that are not. The Impeaching Thesis asserts that when a court decides a case on irrelevant considerations, that fact undermines or impeaches its precedential status. Let me offer two examples of the Impeaching Thesis in action. The first is the 2006 case of Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, in which the Supreme Court considered a challenge to the constitutionality of the Bush Administration’s use of military commissions to try so-called “enemy combatants.” In that case, one of the amicus briefs filed on behalf of Hamdan argued that the Supreme Court’s 1942 decision in Ex parte Quirin, on which the government had relied heavily, was a “poisoned precedent.” The reason was that that decision, which had upheld President Roosevelt’s use of a military commission to try and sentence to death seven German saboteurs, was infected by judicial bias, conflict of interest, and inordinate pressure from President Roosevelt. In so arguing, the amici drew on historical evidence showing that the President had conveyed to the Justices that he “expected—indeed, demanded—unanimous approval of the exercise of his war powers.” The second example comes from the 1996 case of Seminole Tribe vs. Florida, in which the Supreme Court considered whether the Eleventh Amendment prohibited Congress from authorizing federal courts to hear suits brought against a 2 state by one of its own citizens. In holding that the amendment did bar such jurisdiction, the Court placed considerable weight on its 1890 decision, Hans vs. Louisiana, which had offered an expansive interpretation of the Eleventh Amendment. In dissent, Justice Souter argued, with two other justices joining him, that Hans should not be given precedential weight because the Hans Court only gave the interpretation of the Eleventh Amendment it did because it feared it could not enforce its judgments in the post-Reconstruction South. Citing the work of historians, Justice Souter described the political circumstances in which Hans arose and concluded that “history explains, but does not honor, Hans.” Note how the use of history to “impeach” a past court decision in this way differs from other, more conventional uses of history in legal argument. It does not involve using historical evidence to interpret the “original meaning” of a particular statutory or constitutional provision in the way originalists advocate. Nor does it use history to show why social, political, or economic circumstances have changed in a relevant way between the time of the original decision and the present. Instead, it involves arguing that a past decision should not be treated as legally authoritative because historical evidence reveals that the Court may have rendered its decision for reasons other than the reasons the court offered in its opinion. In Ex Parte Quirin, the ulterior motive was a desire to alleviate political pressure placed on the court; in Hans, it was an effort to salvage the court’s institutional legitimacy in the face of its lack of enforcement power. The logic of such arguments is that since we defer to a past court’s interpretation of the Constitution on the assumption 3 that that prior court applied the relevant legal principles in good faith, when historical evidence reveals that assumption to be false – suggesting that instead the court was motivated by something else entirely – we no longer have good reason to defer to its judgment. This kind of historical argument is, of course, controversial. When Justice Souter employed it in Seminole Tribe, Chief Justice Rehnquist denounced the argument on the ground that it “did a disservice to the Court’s traditional method of adjudication.” But the point is that there is no reason why, in principle, such forms of history could not become part of how courts interpret their own precedent. If they were to do so, then history – even what we think of as “external” legal history – would itself become part of legal doctrine. Still, the logic of impeaching arguments depends on two premises, both of which are contestable. First, it depends on the idea that what actually motivated a previous court’s decisions is in fact relevant to why courts treat past decisions as authoritative in the first place. And you might very well deny that. Courts are not engaged in an historical inquiry, one might say, but only in a process of rationalization that enables them to make the best sense of past case outcomes, irrespective of the actual motivations of the judges deciding them. Ronald Dworkin is associated with something like that view of judicial reasoning. I disagree with that view, and I recently wrote a paper challenging it and arguing that under the most plausible theories of stare decisis, both at common law and in the constitutional context, such historical evidence of motivations is indeed 4 relevant to why courts treat past decisions as authoritative. But I want to put that issue aside for now, except to note the following (again, in the spirit of provoking controversy): When historians say, as the organizers of this conference do in their preparatory materials, that legal doctrine is a boring topic “especially for historians of the sort who rightly eschew lawyers’ history as not history at all,” they are playing into the hands of those who would dismiss historical arguments as irrelevant to the concerns of courts and lawyers. That is, when historians accept the view (to summarize crudely) that historians explain while lawyers rationalize, they contribute to the diminishing relevance of history to judicial decisionmaking. The second premise on which the Impeaching Thesis depends is that it is possible to discover why courts have decided cases the way they did. That is, it requires making causal claims about what best explains certain court decisions. Of course, offering such explanations is precisely the kind of thing historians do. But I worry that an understandable reluctance to avoid making claims that extend far beyond what can be established with certainty has encouraged a certain timidity about the very idea of offering causal explanations of historical events. For example, in the introduction to a recent symposium on legal history at UC Irvine (at which I believe some people here were present), Catherine Fisk and Robert Gordon explain that a common feature of the papers presented at the symposium was their implicit agreement that “legal history is not trying to be an empirical social science aiming to identify a series of variables and use the past as an experiment to prove that one or two variables produced particular effects.” 5 Now I may be misunderstanding (and overstating) the suspicion of causal claims voiced here. Perhaps the point is simply that legal historians are reluctant to make general causal claims in the way that the natural and social sciences often do. They are content to offer explanations of particular events, just not general ones about whole classes of events. Hence, the authors of the Introduction go on to say that “is important to explain that somebody did something to, with, or for someone else, for identifiable reasons and with identifiable consequences.” So maybe the problem lies not with causal explanations as such, but rather with the generality of the explanations offered. If that is the concern, then it seems to me a well justified one and one that in no way undermines the Impeaching Thesis. To the contrary, the Impeaching Thesis depends on its truth. For if it were the case that we could derive general causal laws about how judges decide cases, then there would be no need for such particular historical accounts about past decisions. We would already know that courts base their decisions on X (whether X refers to “legal” reasons, politics, economics, selfinterest, or whatever), and there would be little profit in investigating the historical particulars of any given case. The better approach, it seems to me, is to leave it an open question how any given case was decided and then proceed to look at the historical evidence to determine which explanation is most persuasive. Moreover, just this difference – between, on the one hand, looking to the historical context of a particular decision in order to explain why it came out the way it did and, on the other, explaining it by reference to some kind of background statistical 6 generalization – does seem to mark at least one (if not the) important difference between the aims and methods of history and those of the empirical social sciences. Still, I sometimes worry that there’s a deeper skepticism among historians about the possibility or utility of offering “explanations” of even particular historical events. Such skepticism troubles me for both a small and a big reason. The small reason is that it threatens to undermine the Impeaching Thesis, which means reducing the potential significance of so-called “external” legal history for shaping (and even constituting) legal doctrine. The big reason is that it lessens the value of social, political, and intellectual history in general. Here is what I mean: It seems to me that there are broadly two kinds of questions someone acting in the present would want to ask about ideas from the past. The first is about the relative value of the ideas themselves: Are they good or bad ideas, true or false ones? Do they warrant veneration or condemnation? Why or why not? The second kind of question goes to the role the ideas have played in shaping the world we live in today: Did the ideas (whether good or bad, true or false) make a difference in the world? What consequences, if any, did they have for the course of human thought or conduct? In short, did they matter? If so, how? Neither kind of question lends itself to easy answers, and both tend to be sources of perpetual debate. Perhaps for that reason, intellectual historians have mostly abandoned the first, evaluative kind of inquiry. My worry is that if they give up the second one as well, there will be nothing left. 7