freedman: FROM GENRE TO POLITICAL ECONOMY: MIÉVILLE`S

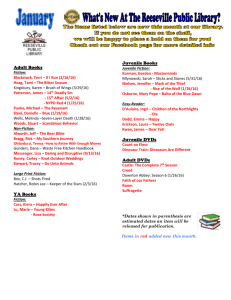

advertisement

freedman: 1 FROM GENRE TO POLITICAL ECONOMY: MIÉVILLE’S THE CITY & THE CITY AND UNEVEN DEVELOPMENT By Carl Freedman From the beginning, China Miéville’s work has been characterized by the combination of a wide range of generic kinds. “Weird fiction,” his own preferred term (borrowed from H. P. Lovecraft) for his work, is in fact an omnibus category that in practice has included elements from such arealistic forms as science fiction, world-building fantasy, horror, Surrealism, and magical realism. This list is not exhaustive, of course, and Miéville has also combined weird fiction as a whole with genres that cannot be considered arealistic in quite the same way. Dickensian urban satire, for example, is prominent in Perdido Street Station (2000); The Scar (2002) owes a good deal to the traditional seafaring narrative as developed by Melville and Conrad; and in Iron Council (2004)—for me his finest novel to date—the Western has an important generic presence (Zane Grey is appropriately listed on the acknowledgements page among the writers to whom Miéville expresses a special debt). In this context, Miéville’s 2009 novel The City & The City marks a significant departure from his earlier work. Here the entire elaborate machinery of weird fiction is mostly—but not totally—dispensed with, and what remains of it is fused with a quite different generic cluster, one composed of such overlapping though by no means identical genres of crime fiction as noir, the police procedural, and (above all) the hard-boiled detective narrative. The generic composition of the novel is further overdetermined by the kind of dystopia invented by Zamyatin and most famously exploited by Orwell, while the nearly unclassifiable influence of Kafka (who is explicitly thanked on the acknowledgements page) faintly but unmistakably haunts the text as a whole. Many readers have noticed that the novel stands strikingly apart from the author’s earlier work on the stylistic level: the voluptuous richness of syntax and vocabulary that freedman: 2 characterizes the best of Miéville’s earlier novels and stories is here replaced by a far leaner and more stripped-down prose, which appears heavily indebted to Dashiell Hammett, the chief founder of hard-boiled detective fiction. Yet it seems to me that the uniqueness of The City & and The City is manifest even more consequentially on the level of genre. It is not a matter just of different genres being in play, but of fundamental generic orientation. To invoke a distinction that I have explored elsewhere, the genres that compose weird fiction are all fundamentally inflationary in tendency: which is to say that they all, in various ways, suggest reality to be richer, stranger, more complex, more surprising—and indeed weirder—than common sense would suppose. Weird fiction necessarily insists on going beyond the mundane, and (especially in its science-fictional version) may thereby create special opportunities for what Ernst Bloch called the utopian function of art by showing a world beyond the privation and violence of the actual to be conceivable; this function is, indeed, exercised with rare brilliance in Iron Council. By contrast, the genres of crime fiction tend to be deflationary and opposed to the idea of utopia. Especially since Hammett, the main tendency of crime fiction has been to assume that there is generally less, rather than more, to reality than may first meet the eye, and that the most ordinary, familiar, unsurprising, and petty of human motives are generally the most consequential. Though crime fiction indulges in overt socio-political speculation far more rarely than science fiction, its default assumption is normally that nothing very much better—or very much worse—than the mundane world we see around us is ever likely to come to pass. The City & The City is set in the twin city-states of Besźel and Ul Qoma, which are located in a this-worldly though never precisely designated area of eastern Europe: somewhere, it appears, between Austria and Asia Minor. In the novel’s one major element of weird fiction, freedman: 3 the two cities are located in precisely the same physical space. How this is possible is never made explicit, though one commentator has taken it for granted that the avant-garde physics of string theory must provide a cognitive justification. In any case, once this donnée is established, the implications of it are worked out with lucidly strict logic. Besźel and Ul Qoma regard one another with suspicion and low-intensity dislike. The two cities have, at various times in the past, supported opposed sides in military conflicts, including the Second World War; and in the time present of the novel they co-exist in a kind of cold peace. Though a small, despised minority of left-wing “unificationists” disagree, the vast majority of citizens are intensely proud of each city’s distinct identity and take for granted the importance of keeping Besźel and Ul Qoma almost completely separate. Such rigorous separation requires citizens to act as though the cities were not “grosstopically” coterminous, and from early childhood every Besź and every Ul Qoman must learn to “unsee” the people, buildings, streets, motor vehicles, and everything else that the other city contains. The authorities of the two cities must consult one another on certain practical matters—shared infrastructure, for example, and intercity smuggling—and it is possible to travel between the cities lawfully through the extraterritorial “Copula Hall.” But any unauthorized and deliberate transgression of the mental barriers between Besźel and Ul Qoma— any “breach,” as it is called—is a crime of the utmost seriousness. Such crime is severely punished by a shadowy and unimaginably powerful police agency named Breach that (like Orwell’s Thought Police) exists apart from, and superior to, the ordinary security forces (of both cities). Despite the weird relationship between Besźel and Ul Qoma, the cities maintain fairly normal relations with the rest of the world, through commercial trade, diplomatic embassies, the internet, international phone calls, air travel, and the like. And, aside from the constant freedman: 4 possibility (and hence the constant fear) of committing breach, everyday life in the twin cities, especially Besźel, does not seem to differ greatly from the mundane post-Soviet eastern European status quo. Like so many crime narratives, The City & The City begins with a strange and startling murder: a young American graduate student who had been doing archeological research in Ul Qoma is found cut to death in Besźel, her body stripped almost naked and deposited in a drab field. The case is assigned to one Tyador Borlú, the novel’s protagonist. Though a senior police investigator of Besźel’s Extreme Crime Squad, Borlú—in his toughness, his general intelligence, his urban street savvy, his basic decency, his staunch individualism, his sexual attractiveness, and his sad essential loneliness—is strongly reminiscent of one of the greatest of all hard-boiled private dicks, Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe (Chandler is one of the writers thanked in the acknowledgements). As Marlowe typically does, Borlú spends the entire book proving himself the sole investigator capable of cracking a baffling case in which the solution to one problem often leads to another and then yet another; and, again as with Marlowe, the details of the investigation are sometimes less memorable than the personal qualities of the detective and, even more, the unfolding revelations about the environment through which he moves. Yet some of the investigative details are important. Mahalia Geary, the murdered student, had been doing research into the early history and prehistory of the twin cities, notably into the little-understood period before their separation; and at many points it seems as though she may have met her death through becoming mixed up in the strange politics that dominate Besźel and Ul Qoma. Mahalia made some contacts among Besź unificationists, and there are right-wing Besź nationalists (of the “True Citizens of Besźel”) who assume her to have been a unificationist herself—or, even worse, an Ul Qoman spy—who got exactly what she deserved. freedman: 5 But the unificationists do not regard her as one of their own. They have come to believe that her interest in them was based not on political sympathy but on the desire to have access to their extensive library of historical documents—and that she was more a danger to them than anything else. Various hypotheses about Mahalia’s life and death are considered and eventually discarded in the course of Borlú’s investigation. By far the most intriguing—and certainly the one that most seems to open up vistas of weird fiction—concerns the possibility of a third city, named Orciny. Though the subject is not considered a fit one for reputable academic scholarship, Mahalia, like many others, has been fascinated by rumors of this third city that not only existed during the distant past of Besźel and Ul Qoma but that, in some accounts, still exists during the time present of the novel. Orciny is supposed to maintain itself in the interstices between the twin cities, occupying areas assumed by the Besź to be Ul Qoman and by the Ul Qomans to be Besź; its inhabitants, it is said, manage to conduct themselves in plain view, taken by the citizens of each of the twin cities to belong to the other, and thus “unseen” by all as quickly as possible. Orciny is credited with awesome powers, comparable to those of Breach itself—to which some believe it to be identical, though others regard the two mysterious forces as arch-enemies. Might Mahalia have been murdered by the agents of this weird third city? Did she, perhaps, learn more about Orciny than the Orcinians wished to be known, and thereby inadvertently bring about her own destruction? The answer is no. The staid, conservative academic view—that Orciny is a mere fable, its supposed existence unsupported by fact—turns out to be the truth. The force behind Mahalia Geary’s murder transpires to be the entirely mundane one of monetary greed: she was killed in order to cover up and protect a perfectly ordinary illegal commercial scheme of the sort that would have been quite familiar to Marlowe (or to Hammett’s Sam Spade, or his Continental Op). freedman: 6 Without meaning to, Mahalia had become involved with the criminals, and, in one of the novel’s more elegant plot twists, it became necessary to eliminate her when she discovered for herself that, her longstanding suspicions to the contrary notwithstanding, Orciny never existed after all. The apparent inflationary possibility—doubtless, for many readers, the inflationary hope—that there is much strange and exciting and even fantastic to be learned about Orciny is cancelled with a deflationary shrug. People do not, as a matter of fact, get killed in order to prevent the existence of uncanny forces from becoming widely known. People get killed so that other people can make money: a point of decisive generic significance. Though the “grosstopic” coexistence of Besźel and Ul Qoma remains an irreducible element of weird fiction within The City & The City, it is ultimately overmatched by the ordinary everyday verities of crime fiction. This is not to deny the genuine importance that weird fiction does possess in the novel’s generic overdetermination. Like the great dystopias of Zamyatin and Orwell, The City & The City is on one level a political satire; but Miéville’s target is less totalitarianism than xenophobic nationalism. The conceit that the twin cities occupy identical physical space ultimately functions as an estranging device (similar, in its way, to Swift’s division of the Lilliputians into Big Endians and Little Endians) that highlights the absurdity and the inherent emptiness of the oppositions over which human beings frequently tear their lives out. The divided city is in real history often an especially pointed example of political futility; and Jerusalem and pre-1989 Berlin are explicitly cited in the novel (though Borlú does not regard them as true analogues to Besźel and Ul Qoma). But Miéville constructs a figure of xenophobic division that is rendered chemically pure, as it were, by being shown to be completely formal. It is not just that, as we gradually become aware, there do not seem to be any substantive issues of ethnicity or religion or political doctrine over which the twin cities are opposed. There is not even any geographical freedman: 7 distinction between the cities, and the barriers that separate them must be constructed in the minds of the inhabitants. It is separation simply and solely for separation’s sake. Nonetheless, people do construct these separating mental barriers, which are strong enough to support an elaborate system of repressive state apparatuses and an entire ideological way of life. Some people, like the True Citizens, are even capable of specially devoting their lives to the reaffirmation of the substantively empty divisions between the twin cities. Miéville himself would surely be a unificationist if he lived in Besźel or Ul Qoma. But, by portraying the unificationists as marginalized and ineffective, he underlines the insane power of pathological nationalism. We need, however, to examine the politics of the two cities a bit more closely in order to appreciate just how deflationary The City & The City really is. The political history of Besźel and Ul Qoma is in fact difficult to reconstruct in complete detail. The eastern European location suggests both city-states to have once belonged to the now dismantled Soviet bloc, or possibly to the equally dismantled Yugoslavia. That history seems to survive in, for example, the Besź term commissar—which, however, is not used in Ul Qoma, where the word has a distinctly foreign ring, and where, during the time present of the text, there are no legally permissible socialist (or other oppositional) political parties. Ul Qoma, however, may have had the more radically socialist tradition, for at one point we learn that, during the 1960s, it was, along with Castro’s Cuba and Mao’s China, a favored destination for expatriated American radicals. Still, it is hard to see why Ul Qoma should still, in the present time, be subject to economic sanctions imposed by the US State Department, while Besźel maintains normal relations with Washington. It is even harder to see why, given this geopolitical situation, Besźel should retain the drab industrial look stereotypical of Soviet-bloc urban geography, and the concomitant relatively low level of technology (“Washington loves us, and all we’ve got to show for it is Coke” [194], as Borlú freedman: 8 comments bitterly in conversation with an Ul Qoman colleague); while Ul Qoma, in contrast, looks and feels considerably more “modern” in the way made possible by the massive presence of Western consumer capital. Why all the unanswered questions? Miéville’s grasp of modern geopolitics is as firm as that of any novelist at work today (not for nothing is he an important Marxist scholar of international law), and he would certainly have made these matters crystal clear if he had intended to. But the deliberate scantiness of detail serves an aspect of the text’s satiric tendency. Bernard Shaw—perhaps the greatest of British satiric writers since Swift and one of Miéville’s own numerous precursors—found the foibles of the small nations of eastern Europe to provide, in their pettiness and inherent inconsequentiality, an especially rich subject-matter for the mockery of nationalist politics and national self-importance; and there is, I think, more than a whiff of Arms and the Man (1894) in The City and The City. If it is difficult to be totally clear about the details of Shaw’s Balkans or Miéville’s invented cities, this is because the details are not really worth bothering about: they are so petty as to be negligible from any genuinely geopolitical perspective. Yet the Irish-born Shaw hardly regards his characters with self- satisfied English jingoism; and the real satiric target of Arms and the Man is not only the nationalism of Bulgaria but that of the British Empire itself. The absurdity of a dwarf may be particularly easy to see and convenient to ridicule; but it is not essentially different (save by being a good deal less dangerous) from the absurdity of a giant. The giant global power to which Besźel and Ul Qoma are contrasted and compared is of course not the long-defunct British Empire but US-dominated multinational capital; and, unlike the Shavian precedent, Miéville’s novel makes the contrast fully explicit. As usual with this author, the text is structured not only on an overdetermined hybridity of genres but, at a deeper freedman: 9 level, on problems of political economy; and here the chief problem is uneven development. As this extraordinarily complex concept has been developed from Marx and Engels through such later thinkers as Trotsky, Ernest Mandel, Walter Rodney, and David Harvey, it refers not merely to the empirical and apparently contingent fact that some social formations enjoy a more advanced stage of economic development than others: as, for example, Besźel and Ul Qoma seem to, much to the considerable envy of a Besź character like Borlú. Far more important is that uneven development functions as a motor of capital accumulation, and thus that developmental unevenness is not a contingent by-product of the capitalist mode of production but is structurally integral to the latter: the very title of Rodney’s classic study, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972), makes the point succinctly. The formal imperialism that Shaw satirized and Rodney analyzed amounts to one theatre in which uneven development can operate. But The City and The City tackles uneven development in the contemporary world where imperialism has been for the most part superseded by Empire (in the by now canonical Hardtand-Negri sense). This theme is sounded throughout the novel. In the opening chapter, for instance, we are casually informed that the increasingly aggressive and salacious tone of the Besź press is the work of newspapers “started, inspired and in some cases controlled by British or North American owners” (11). Relatively early in his investigation, Borlú finds that some higher authorities he needs to consult may be unavailable for a few days while they are attending to commercial matters: and, as a police colleague informs him, they are “not going to shunt off business meetings and whatnot like they would’ve done once.” “Whoring it for the Yankee dollar” (57), replies Borlú with perfect understanding. But the dominance of Besźel and Ul Qoma by the Empire of global capital is emphasized to greatest effect at the end of the novel in connection freedman: 10 with Borlú’s ultimate success in solving the murder of Mahalia Geary. It turns out that the scheme with which she inadvertently became involved, and for which she was killed, was devoted to the illegal sale of ancient Besź artifacts to a giant multinational corporation; and, in a particularly nice irony, several True Citizens working with this criminal operation are revealed to be, despite all their professed Besź patriotism, “just a fence for foreign bucks” (285), as Borlú puts it. Yet even Borlú, for all his shrewdness, does not fully appreciate the almost comical gulf in stature that separates anything in Besźel or Ul Qoma from the true masters of the universe. When, at the end of The City & The City, Borlú, now working for Breach, confronts one of these masters—an evidently American executive of the corporation that has been buying the artifacts—he expects that the fear and awe with which Besź and Ul Qomans hold Breach will carry the day for him. But the American is simply amused: “You think anyone beyond these odd little cities cares about you?. . . .What do you think would happen if you provoked the ire of my government? It’s funny enough the idea of either Besźel or Ul Qoma going to war against a real country. Let alone you, Breach” (287). The executive takes off in his company helicopter, and the man ultimately most responsible for Mahalia’s murder escapes scot-free. Beyond the deflationary generic conventions of crime fiction—but by no means unrelated to them—lies the most powerful deflationary force in our world structured by uneven development: the Yankee dollar.