Proceedings Template - WORD

advertisement

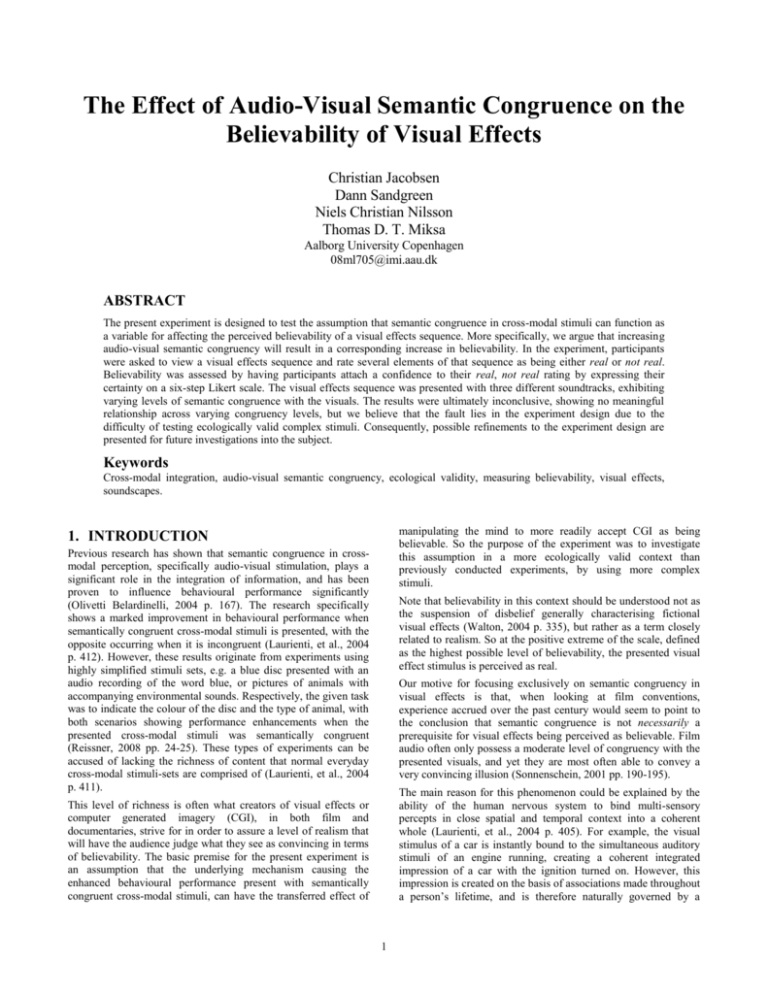

The Effect of Audio-Visual Semantic Congruence on the Believability of Visual Effects Christian Jacobsen Dann Sandgreen Niels Christian Nilsson Thomas D. T. Miksa Aalborg University Copenhagen 08ml705@imi.aau.dk ABSTRACT The present experiment is designed to test the assumption that semantic congruence in cross-modal stimuli can function as a variable for affecting the perceived believability of a visual effects sequence. More specifically, we argue that increasing audio-visual semantic congruency will result in a corresponding increase in believability. In the experiment, participants were asked to view a visual effects sequence and rate several elements of that sequence as being either real or not real. Believability was assessed by having participants attach a confidence to their real, not real rating by expressing their certainty on a six-step Likert scale. The visual effects sequence was presented with three different soundtracks, exhibiting varying levels of semantic congruence with the visuals. The results were ultimately inconclusive, showing no meaningful relationship across varying congruency levels, but we believe that the fault lies in the experiment design due to the difficulty of testing ecologically valid complex stimuli. Consequently, possible refinements to the experiment design are presented for future investigations into the subject. Keywords Cross-modal integration, audio-visual semantic congruency, ecological validity, measuring believability, visual effects, soundscapes. manipulating the mind to more readily accept CGI as being believable. So the purpose of the experiment was to investigate this assumption in a more ecologically valid context than previously conducted experiments, by using more complex stimuli. 1. INTRODUCTION Previous research has shown that semantic congruence in crossmodal perception, specifically audio-visual stimulation, plays a significant role in the integration of information, and has been proven to influence behavioural performance significantly (Olivetti Belardinelli, 2004 p. 167). The research specifically shows a marked improvement in behavioural performance when semantically congruent cross-modal stimuli is presented, with the opposite occurring when it is incongruent (Laurienti, et al., 2004 p. 412). However, these results originate from experiments using highly simplified stimuli sets, e.g. a blue disc presented with an audio recording of the word blue, or pictures of animals with accompanying environmental sounds. Respectively, the given task was to indicate the colour of the disc and the type of animal, with both scenarios showing performance enhancements when the presented cross-modal stimuli was semantically congruent (Reissner, 2008 pp. 24-25). These types of experiments can be accused of lacking the richness of content that normal everyday cross-modal stimuli-sets are comprised of (Laurienti, et al., 2004 p. 411). Note that believability in this context should be understood not as the suspension of disbelief generally characterising fictional visual effects (Walton, 2004 p. 335), but rather as a term closely related to realism. So at the positive extreme of the scale, defined as the highest possible level of believability, the presented visual effect stimulus is perceived as real. Our motive for focusing exclusively on semantic congruency in visual effects is that, when looking at film conventions, experience accrued over the past century would seem to point to the conclusion that semantic congruence is not necessarily a prerequisite for visual effects being perceived as believable. Film audio often only possess a moderate level of congruency with the presented visuals, and yet they are most often able to convey a very convincing illusion (Sonnenschein, 2001 pp. 190-195). The main reason for this phenomenon could be explained by the ability of the human nervous system to bind multi-sensory percepts in close spatial and temporal context into a coherent whole (Laurienti, et al., 2004 p. 405). For example, the visual stimulus of a car is instantly bound to the simultaneous auditory stimuli of an engine running, creating a coherent integrated impression of a car with the ignition turned on. However, this impression is created on the basis of associations made throughout a person’s lifetime, and is therefore naturally governed by a This level of richness is often what creators of visual effects or computer generated imagery (CGI), in both film and documentaries, strive for in order to assure a level of realism that will have the audience judge what they see as convincing in terms of believability. The basic premise for the present experiment is an assumption that the underlying mechanism causing the enhanced behavioural performance present with semantically congruent cross-modal stimuli, can have the transferred effect of 1 contextual or semantic inference based on the person’s accumulated experience (Laurienti, et al., 2004 p. 406). Consequently, the believability of visual effects must inevitably be governed by semantic content, as well as spatial and temporal parameters. form of binary evaluation was insufficient since the present experiment sought to investigate the degree to which the variable congruency components were perceived as real. In order to make up for this deficiency, the binary rating was coupled with a certainty score making the overall measurement of believability gradable. An added benefit was that this form of believability assessment, contrary to the binary rating, would produce analysable results even if all ratings turned out to be not real. Based on the presented information, our assumption was that audio-visual semantic congruency could work as a variable for affecting the believability of visual effects, and the experiment presented in this paper was designed to investigate if this claim would hold in practice. This assumption is expressed in the hypothesis presented in the following section. 2.1 Participants The participants partaking in the experiment comprised 60 adult volunteers (mean age 25 years, 43 males, and 17 females) with self-reported normal hearing and normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The participants were selected by addressing arbitrary people at the Copenhagen University College of Engineering and Aalborg University Copenhagen, making the employed sampling technique classifiable as convenience sampling (Trochim, 2006). All the participants were consequently Medialogy undergraduate students, engineering students, faculty, or other employees at these two educational institutions. When assigning the participants to the three experimental conditions, the aspiration was to assign an equal number of Medialogy students, engineering students, faculty and other employees to each of the three groups. This was believed to reduce the possible bias induced by the difference in theoretical and practical knowledge of visual effects accompanying the different educational backgrounds. All participants gave written informed consent and were offered a beverage for participating. 1.1 Hypothesis By presenting a visual effects sequence with increasingly semantically congruent soundtracks, a corresponding increase in perceived believability of the visual effects will be present and measurable. 2. EXPERIMENT DESIGN The experiment follows the overall paradigm of independent group design. One visual effects sequence and three different soundtracks were specifically designed for the experiment which was carried out spanning three similar groups of individuals. The operational definition of the independent variable audiovisual semantic congruence does, in principle, only necessitate two levels of congruency within the context of the present experiment. More specifically, a comparison of the effects of high and low congruency should suffice when attempting to determine if the believability of visual effects changes as the result of difference in congruency. However, an independent variable with only two levels does not provide much information about the relationship between it and the dependent variable (Cozby, 1997 p. 147). Simply using a high and low level of congruency would for instance provide little and possibly even faulty information about how a soundtrack conforming to the aforementioned film conventions would influence believability. Hence, the independent variable audio-visual semantic congruency was designed to have three levels. As the experiment revolved around how an increasingly congruent soundtrack would influence the believability of the visual effects, the stimuli defining the level of audio-visual semantic congruence necessarily had to be the audio. 2.2 Stimuli Two categories of stimuli had to be designed for the experiment; namely visual and auditory stimuli. As outlined in the first paragraph of this section, the auditory stimuli constituted the independent variable while the visual stimuli comprised the dependent variable of the experiment. More accurately, the dependent variable was the subjective believability of the visual stimuli; the end result being that a single visual sequence was needed while three different auditory stimuli sets were required. The following two subsections outline the functional and aesthetic choices made in designing these different sets of stimuli. 2.2.1 Visual stimuli The dependent variable believability can be operationally defined as the degree to which the individual computer generated elements of a visual effects sequence are mistakable for their real world correlates. Here the individuality of the visual elements is stressed; since the believability of each element may change as a result of variations in the unique auditory components associated with them. Visual elements with varying audio across the three levels of semantic congruence will throughout the following be referred to as variable congruency components. Three primary requirements had to be satisfied in creating the visual stimuli. First; it should contain four congruency components for the audio to work with, i.e. components that have a variable semantic congruency connection to a corresponding auditory element. Second; the computer generated elements would have to exhibit a high level of realism to be useful in this experimental context; in other words, they should to some extent be believable as real objects. And third; in order to be perceived as believable, the content should also be relatable to personal experience for the intended audience to judge properly. The thematic choice for the final sequence was the concept of a computer generated thunderstorm. Whereas believability within some contexts may be scalable it is less certain whether perceived realism is gradable or not. So far, no evidence suggests that we are able to distinguish between more than two grades of real (Rademacher, 2002 p. 25). This arguably implies that we possess a single internal threshold determining whether we consider a given percept to be real or not (Rademacher, 2002 pp. 81-82). The present experiment adopts this stance entailing that the believability of the individual computer generated elements first and foremost is defined by whether they are regarded as either real or not real. However, this The primary reason for choosing the theme of a thunderstorm lay in the animations. With the thunderstorm theme we were able to create a dynamic sequence with large amounts of moving elements present. It also enabled us to rely on physics based systems, e.g. wind and gravity, and consequently avoid any animation problems associated with the Uncanny Valley; where 2 suboptimal animations can lead to uncanny movement that would certainly compromise the believability factor (Bartneck, et al., 2007 p. 368). to not make the tested elements stand out. These added elements consists of the grass, the mountains, the background trees as well as the foreground branch occasionally visible in the upper left corner of the frame. An equally important reason for adding these experimentally extraneous elements, were that a certain level of complexity was needed in the scene to reach a desirable level of ecological validity. To elaborate, a final sequence with low consistency in the form of visibly missing elements would not provide the desired ecological validity or stimuli complexity. The final visual effect sequence is set in a location resembling the African savannah, a thematic choice based solely on aesthetic considerations, with a view over a great grass field, a tree in the middleground and flashing thunderclouds raging above. Half way through the sequence, the tree is struck by lightning and breaks apart at the lower forked part of the trunk and is subsequently engulfed in flames. The four visual elements chosen as variable congruency components were; the thunderclaps, the lightning strike, the tree breaking, and the fire, all elements deemed to have a high level of semantic familiarity. In other words, both the auditory and visual stimuli associated with the four chosen components, as well as the connection between them, should be highly familiar to all but a few test subjects, even when doing convenience based sampling. Additional information concerning the visual stimuli can be found in the exam enclosure under visual design. The three video sequences used for the experiment can be found on the appended CD in the folder experiment stimuli. 2.2.2 Auditory stimuli An important feature of the auditory stimuli was that it had to compliment the visual stimuli in creating the sense of being situated on the African savannah. Creating a sonic impression of being in a specific location is a common practice in the film industry and referred to as a soundscape; defined by film sound theorist Rick Altman as “the characteristic types of sound commonly heard in a given period or location” (Altman, 1992 p. 252). Initially, a choice had to be made between creating a purely virtual sequence with no real objects present, or a composite shot containing live action footage as well as computer generated elements. The purely virtual sequence was the better choice for two main reasons; one, we did not have easy access to a location that corresponded visually to the chosen theme of the African savannah; and two, the presence of real footage alongside the computer generated elements could lead to quality requirements of the virtual elements that we might not be able to satisfy. Consequently, the final sequence consists solely of virtual computer generated elements. The reason why this was an acceptable compromise was because the elements ultimately need not be rated as real to provide usable test results, an argument that was established earlier in this section. Figure 1 shows a screenshot from the final visual effects sequence. The characteristic sounds for the African savannah were identified as cicada shrill, wind, trees and vegetation swaying in the wind; all referenced from a savannah documentary (BBC, 2005). Additional auditory elements for the thunderstorm were identified as thunderclaps, lightning strikes, rustling leaves, tree cracking, falling, burning and fire. Establishing a soundscape for a savannah thunderstorm delimited what the three soundtracks should contain, and following this delimitation the semantic components needed to be varied through three levels of congruency; high, medium and low. This meant one level for each soundtrack linked to the four variable congruency components; the thunderclaps, the lightning strike, the tree breaking, and the fire. The auditory elements in the soundtracks were mixed as if captured with a microphone mounted on a camera. Additionally, the function of the three soundtracks is, unlike those common in film, not designed to guide the viewer’s attention to specific narrative elements in the sequence (Sonnenschein, 2001 pp. 195198). Instead, they function to create believable soundscapes that place the viewer on the savannah during a thunderstorm. Since all the visual components in the sequence are computer generated they obviously have no inherent capability of generating any sonic characteristics. Their audio elements could therefore never be truly congruent, thus the reason to denote the congruency level high as opposed to real. In this regard, the semantic criterion for the high congruency soundtrack was that its audio elements were recordings of authentic events correlating as close as possible to the events as they would have occurred in the real world. For example, when a part of the tree trunk breaks, the sound of actual wood breaking should be heard in order to facilitate a high semantic audio-visual congruency. Figure 1 - Screenshot from the final visual effects sequence. With the intention of obtaining believable camera motion, and at the same time acquire real world scenery to build the virtual scene on, the sequence was based on live action footage, consequently meaning that while all elements in the final sequence are computer generated, the camera movements are transferred directly from the live action footage. Since there are no real objects present in the sequence, several elements, aside from the four variable congruency components, had to be added in order to create a consistent holistic impression of the sequence, as well as The technique used for the medium congruency level is similar to what is commonly denoted as Foley effects, a term known from the film industry. A Foley effect is a recreation of an audio event on a soundtrack which, although meant to support the believability of a scene (Wyat, et al., 2007 pp. 166-167), is 3 produced by objects that sound similar but not necessarily directly correspond to the visuals presented (Singer, 2008). The participants were asked to evaluate whether the individual elements were real or not real. The option, don’t remember, was also made available in case the participants did not remember seeing certain elements in the sequence. For each realism rating the participants additionally had to specify how certain they were on a six point Likert scale; where one signified, very uncertain and six very certain. The order in which the different elements were presented on paper was pseudo randomized. More specifically, three different types of questionnaires containing the same items in three different orders were randomly assigned to the participants. This ensured that all items on the questionnaire appeared in the first, second and last third of the questionnaire an equal number of times, thus reducing the risk of order effects (Cozby, 1997 p. 118). As a result, the criterion for the medium congruency soundtrack was that the audio elements should consist of sonic characteristics similar to those used in the high congruency one, but instead consists of recorded audio comprising a wide semantic gap to the viewed events. For example, the audible thunderclaps were not actual thunderclaps, but instead generated through recordings of rockslides containing similar frequency characteristics and amplitude envelopes, with applied post-processing effects emphasizing audio characteristics similar to those of real thunderclaps. Lastly, the semantic criterion for the low congruency soundtrack was that the audio elements should only correlate to the same basic type of audio events occurring in the sequence, e.g. the burning branch hitting the ground is accompanied by an impact sound. Consequently, the semantic components carried a lowered congruency in using audio events with material properties conflicting with the properties in the sequence. For example, by linking the audio event; branch hitting ground, with a brick hitting a metal surface instead of the more congruent wood and leaves hitting dirt. A reference image labelled with the names of the elements, intended to aid the participants in identifying elements, was provided after they had watched the sequence. The quality of the image was, however, greatly reduced making it impossible to use it as a reference when evaluating the individual elements. The participants were additionally informed that the sole purpose of the image was to help them distinguish between the different items in the questionnaire. Additional information concerning the auditory stimuli can be found in the exam enclosure under audio design. A soundtrack comparison video can be found on the appended CD in the folder experiment stimuli. All material pertaining to the experimental procedure can be found on the appended CD in the folder experiment design. 2.4 Data Analysis The nine items on the questionnaire, each corresponding to an element in the sequence, were analyzed independently of one another. The three possible answers - real, not real and don’t remember - associated with the realism rating were treated as nominal data yielding a Chi-square test for statistical significance (Cozby, 1997 p. 214). These results will be referred to as nominal ratings throughout the rest of the paper. The level of certainty obtained from the Likert scales were treated as interval data and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for significant difference between group means (Cozby, 1997 p. 215). As the ANOVA only account for the overall effect of the independent variable, t-tests were employed to investigate the differences between the individual congruency level groups (Tullis, et al., 2008 p. 31). All statistical tests were performed with a significance level α = 0,05 entailing that p < α would indicate a statistical difference. 2.3 Procedure The objective of the experiment was to measure how the participants passively assessed the believability of the sequence, since this resembled the form of assessment associated with watching a film (Rademacher, 2002 p. 27). The information supplied prior to the participants watching the sequence did for this reason not specify what they were to evaluate, but simply that they were to evaluate the sequence after watching it. An independent groups design was employed for the experiment, entailing that each participant only experienced one of the three levels of audio-visual semantic congruence. Each group comprised 20 participants. The visual stimuli was displayed in its original resolution (720x576) on a 14,1" WXGA+ screen with a resolution of 1440x900, using Monacor MD-4300 headphones to present the auditory stimuli. Volume, brightness and contrast levels were adjusted in advance and were identical for all participants. Assuming that the results were statistically significant, the hypothesis would be supported if; an increase in the level of audio-visual semantic congruence would result in more people rating the variable congruency components as real. A similar pattern should emerge in relation to the level of certainty accompanying the real ratings. Here the group averages should increase as the participants would become increasingly certain that these elements are in fact real. The participants who rated certain elements in the sequence as being not real should conversely become increasingly doubtful as the level of audiovisual semantic congruence increased. After experiencing the sequence, participants were asked to account for their initial impression of the individual elements in the sequence by filling out a questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised the following nine items out of which four was related to the variable congruency components (written in italic): The grass, the foreground branch, the lightning strike, the background trees, the mountains, the clouds, the middleground tree, the fire and the rain. Please note that the clouds-item in the questionnaire comprise both the clouds and the associated thunder claps. The five visual elements without a varying semantic component were included for two reasons. First; to mask the significance of the variable congruency components and secondly; to investigate if the changes in audio-visual semantic congruence also would influence how the non-varying congruency elements were perceived. 3. RESULTS This section first and foremost outlines the results related to the four variable congruency components as these had direct relevance for testing the hypothesis. For the nominal data, frequency distributions are reported, while for the certainty ratings mean distributions are reported including the standard deviation. 4 An Excel sheet containing the complete dataset, the associated graphs and significance tests can be found on the appended CD in the folder experiment design. Fire - Rating frequency per group Real 3.1 Nominal Ratings Frequency of ratings 6 4 Low datasets generally had a slightly larger number of don’t remember ratings distributed across the three levels of congruence than the four variable congruency components. Neither of the calculated p-values for the four variable congruency components, nor the remaining visual elements, were lower than the selected significance level α = 0.05. This implies that none of the frequencies of ratings for the three congruency levels of each dataset are statistically different from one another (Nelson, 1999 p. 91). 3.2 Mean Certainty Levels The mean levels of certainty associated with the real ratings of the middleground tree were 4.0±0.8 for low congruence, 4.5±1.4 for medium congruence, and 4.6±0.7 for high congruence. The corresponding mean levels of certainty for the not real ratings were 4.4±0.9 for low congruence, 4.1±1.4 for medium congruence, and 4.8±1.1 for high congruence. For the participants who rated the lightning strike as real, the mean levels of certainty were 3.9±0.5 for low congruence, 3.6±0.9 for medium congruence, and 5.2±0.8 for high congruence. For the not real ratings the averages were 4.5±0.7 for low congruence, 4.3±1.2 for medium congruence, and 5.0±1.0 for high congruence. The mean levels of certainty related to the real ratings of the fire were 3.8±1.1 for low congruence, 3.9±1.5 for medium Clouds - Average certainty per group Clouds - Average certainty per group Real ratings Not real ratings 6 12 5 5 8 6 4 4 3 2 1 2 0 Level of certainty 6 Level of certainty 14 10 Low Medium High Level of audio-visual semantic congruence Figure 3 - The frequency distribution of the nominal data for the clouds. 0 High Figure 2 - Frequency distribution of the nominal data for the fire. The remaining five datasets in the sequence showed little or no indication of any significant patterns in the distribution of frequencies across groups. It is additionally notable that these five Don't remember Medium Level of audio-visual semantic congruence The nominal ratings related to the clouds showed more irregular variation in the frequencies across the three groups. At the lowest level of audio-visual semantic congruence, 14 of 20 rated the clouds real while 6 rated them not real. Out of the 20 people who experienced the medium level of congruency, 6 rated the clouds real while 13 rated them not real. Finally, the clouds accompanied by highly congruent audio were perceived as real by 10 participants and not real by 6 participants. Note that 4 out of the 20 participants experiencing this soundtrack did not remember the clouds. The bar chart in figure 3 illustrates the frequency distribution of the nominal ratings for the clouds. Frequency of ratings 8 0 The number of participants who rated the fire as real increased together with the level of audio-visual semantic congruence. More specifically, the frequency of real ratings was 6 for low congruence, 7 for medium congruence, and 9 for high congruence. Conversely, the frequency of not real ratings decreased in that 14 rated the fire not real for low congruence, 12 for medium congruence, and 10 for high congruence. The bar chart displayed in figure 2 illustrates how these nominal ratings were distributed across the three groups. Clouds - Rating frequency per group 10 2 A somewhat similar distribution of nominal ratings was apparent from data related to the lightning strike. Here the number of real and not real ratings for low and high congruence was identical. More specifically, 11 of 20 participants rated the lightning strike real while 8 rated it not real. The lightning strike in the sequence with a medium level of congruency was rated both real and not real by 10 of the 20 participants. Not real Don't remember 12 The number of people who rated the middleground tree as real and not real was close to identical for all three levels of audiovisual semantic congruence. The biggest difference being that 10 out of 20 rated the tree as not real for medium congruence, while 8 rated the high and low congruence not real. The number of real ratings was 9 for low congruence and 10 for both medium and high congruence. Real Not real 14 4 3 2 1 Low Medium High Congruency groups Figure 4 - Mean certainty levels for the clouds rated real. Error bars indicate ± standard deviation from the mean. 5 0 Low Medium High Congruency groups Figure 5 - Mean certainty levels for the clouds rated not real. Error bars indicate ± standard deviation from the mean. congruence, and 4.8±0.7 for high congruence. The corresponding mean values for the not real ratings were 4.8±1.1 for low congruence, 5.0±0.6 for medium congruence, and 4.8±1.5 for high congruence. Within the category of stimuli design, one possible mitigating factor could be the quality of the visual stimuli. Qualitative observations during testing combined with the number of real ratings would seem to indicate that this was not a factor; however, there is insufficient data to rule it out completely. Another possible factor was the complexity of the visual stimuli. The number of extraneous elements not directly related to the experiment could have significantly affected test participants subjective assessment of the variable congruency components. This visual density of the sequence coupled with the fact that the soundtracks were not intentionally designed to focus the attention of the participants, prevented us from being able to accurately predict what elements the participants would be aware of; something that is strongly highlighted by the arbitrary distribution of the don’t remember ratings. Additionally, the semantic difference between the three congruency levels could have been too small to properly differentiate the three soundtracks. This issue would not be readily apparent in the test data with such a relatively small sample size, and with no qualitative data to dismiss the claim we have to acknowledge it as a possible source of error. Finally, the mean certainty levels associated with the clouds rated as real were 3.9±1.0 for low congruence, 4.5±0.8 for medium congruence, and 4.8±0.7 for high congruence. The mean certainties for the not real ratings were oppositely 4.5±0.8 for low congruence, 4.2±1.4 for medium congruence, and 4.1±0.9 for high congruence. Figure 4 and figure 5 illustrate the mean certainty of the real and not real ratings for the clouds. The mean certainty levels connected with the real and not real ratings of the remaining five elements in the sequence roughly correspond to the data sets reported for the middleground tree, the lightning strike, and the fire. Neither of the ANOVAs comparing the individual sets of certainty levels for each of the elements rated real revealed any significant difference. This was also the case for the comparison of certainty levels accompanying the not real ratings since all pvalues were higher than the selected significance level α = 0.05. With one exception, all t-tests showed no significant differences between the three groups for neither real nor not real ratings. The t-test used to compare the high and low congruence certainty for the clouds which were rated as real, indicated a significant difference in that p=0.03. In the category of test design, the overriding flaw that is likely to have affected participant response was the phrasing of the real, not real rating. Qualitative observations pointed to some participants interpreting the real ratings as appearing real. This tendency could likely have been offset by phrasing the question differently, e.g. real-world object versus computer generated object. More specifically, this would have established a framework for the term real to operate within (Rademacher, 2002 p. 3). Questions regarding elements that did not have a variable semantic connection were included to mask the significance of the variable congruency components, but also to investigate whether the varying congruency levels would affect the subjective ratings of said elements. This decision could further have exacerbated the issues created by the visual density of the sequence. Together, these two factors are likely to have saturated test participants memory capacity and consequently affected their assessment of the variable congruency components, all the while adding directly to the number of don’t remember ratings. This saturation effect could be explained by the limited short term memory capacity of the test participants, common to all human beings, leading to capacity overflow. If the participants’ attention was not directed at the variable congruency components, this capacity overflow could have prevented them from storing relevant information in either working or long-term memory, subsequently preventing them from accurately assessing the nominal ratings of the four congruency components (Sutcliffe, 2003 p. 38). Conversely, the four variable congruency components arguably have a moderate to high attentional salience by virtue of the movement, vivid colours, or contrast to the remaining elements of the sequence. This attentional salience could have counteracted the saturation issue (Sutcliffe, 2003 p. 29). 4. DISCUSSION Ultimately, the experimental results are inconclusive and statistically insignificant across the board. With that said, there were some individual data sets that showed somewhat weak, but interesting tendencies. The nominal rating of the fire showed indication of a concomitant relationship between an increasing level of congruency and the number of ratings marked as real. This relationship is in concordance with the ideal test data established in the section on data analysis, and could be interpreted as being in support of the hypothesis. The level of certainty tied to the nominal rating shows similar indications, albeit less clear, with the certainty of the real ratings showing the same tendency as the nominal ratings. However, the significance of this is diminished by the fact that the certainty of the not real ratings does not show an inverse tendency, i.e. certainty does not decrease with an increasing level of congruency. Conversely, both certainty levels pertaining to the clouds show the desired tendency; with certainty of the real ratings rising in concordance with the congruency level, and the not real certainty having the inverse inclination. However, the significance of this data set is diminished by the fact that the nominal rating of the clouds shows no meaningful tendencies across the congruency levels. The remaining components with variable congruency levels, i.e. the lightning strike and the tree breaking, showed no relationships between certainty ratings and no meaningful tendencies in the nominal ratings. General care was taken not to prime the test participants, however, this could also constitute a flaw in the design since directed attention is governed both by perceptive stimuli as well as background knowledge (Sutcliffe, 2003 p. 29). With no priming, it could have made the assessment for the test participants more difficult than need be. Finally, since the test was performed across independent groups it does not account for subjectivity of the test participants, and the sample size was not large enough to counteract this factor. Consequently, the variations in the test data The inclination so far based on the interpretations of the data would lean towards a rejection of the hypothesis. This verdict is likely unfounded as there are several mitigating factors that argue against both rejection and acceptance of the hypothesis. The mitigating factors can roughly be divided into two categories; the design of the stimuli presented to the test participants and the design of the test procedure. 6 could just be random fluctuations completely unrelated to the congruency levels, something that is supported by the lack of statistical significance across the board. Cozby Poul C. Methods in Behavioural Research [Book]. - Mountain View : Mayfield Publishing Company, 1997. - 6th Edition. - ISBN: 155934-659-0. A more general mitigating factor could be the general dominance of the visual modality (Sinnett, et al., 2007 s. 673) acting as a natural inhibitor on the effect of the soundtracks. Additionally, it could be argued that people have a high tolerance for moderately incongruent cross-modal stimuli due to the prevalence of said incongruence in films. Laurienti Paul J. [et al.] Semantic congruence is a critical factor in multisensory behavioral performance [Journal] // Experimental Brain Research. - [s.l.] : Springer, 2004. - pp. 405 - 414. Nelson Stephen L. Mba's Guide to Microsoft Excel 2000: The Essential Excel Reference for Business Professionals [Book]. - [s.l.] : Redmond Technology Press, 1999. - ISBN: 978-0967298108. Olivetti Belardinelli M. and Sestieri, C. and Matteo, R. and Delogu, F. and Gratta, C. and Ferretti, A. and Caulo, M. and Tartaro, A. and Romani, G. Audio-visual crossmodal interactions in environmental perception: an fMRI investigation [Journal] // Cognitive Processing. [s.l.] : Springer, 2004. - pp. 167 - 174. The common denominator to most of these mitigating factors is that they are occurring as a result of the attempt at making the experiment ecologically valid. Upon reflection it would appear that a more appropriate method would be to test a visual effects sequence containing only one varying congruency component. A certain complexity would still be needed to make the experiment ecologically valid, but great care should be taken to ensure that all extraneous elements remain as non-intrusive as possible. Furthermore, the considerations concerning the test design should also be adhered to and consequently the only real, not real question posed, should pertain to the single variable congruency component present in the sequence. Adopting such a methodology, we feel, would procure more lucid and cogent results. Rademacher Pablo M. Measuring the Perceived Visual Realism of Images [Report] / Department of Computer Science ; University of North Carolina. - Chapel Hill : [s.n.], 2002. - Ph.D thesis. Reissner T. M. Hearing this while seeing that: Semantic congruence affects processing of audiovisual stimuli [Report]. - Braunschweig : Der Technischen Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, 2008. Singer Philip Rodrigues How It's Done... [Online] // Art of Foley. - 13 December 2008. - 13 December 2008. - http://www.marblehead.net/foley/. Sinnett Scott, Spence Charles and Soto-Faraco Salvador Visual dominance and attention: The Colavita effect revisited [Journal] // Perception & Psychophysics. - [s.l.] : Psychonomic Society Publications, 2007. - Number 5 : Vol. 69. - pp. 673-686. 5. CONCLUSION Inconclusive test results notwithstanding, we still feel confident that there is a connection present between perceived believability and audio-visual semantic congruency. Unfortunately, we were not able to measure this connection with the present experiment design. By applying the changes to the test design outlined in the discussion and designing a simpler, but still ecologically valid, visual effects sequence with a comparatively simple soundtrack; the claimed semantic congruency connection should be measurable. Sonnenschein David Sound Design - The Expressive Power of Music, Voice, and Sound Effects in Cinema [Book]. - Studio City : [s.n.], 2001. Sutcliffe Alastair Cognitive Psychology for Multimedia Information Processing [Book Section] // Multimedia and Virtual Reality: Designing Multisensory User Interfaces. - London : LEA publishers, 2003. Trochim William M.K. Nonprobability Sampling [Online] // Research Methods Knowledge Base. - 20 October 2006. - 16 December 2008. http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/sampnon.php. Tullis Thomas and Albert William Measuring the User Experience: Collecting, Analyzing, and Presenting Usability Metrics [Book]. Burlington : Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 2008. - ISBN: 9780123735584. 6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank Luis E. Bruni for constructive conversations on semantic congruency, Camilla Hägg for help with retrieving the raw camera footage, Gry Poulsen for advice regarding statistics, and Daniel and Martin Miksa for helping with audio field recording. Walton K.L. Fearing Fictions [Book Section] // Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art: The Analytic Tradition - An Anthology / book auth. Lamarque Peter and Olsen Stein Haugom.. - [s.l.] : Blackwell Publishing, 2004. Wyat Hilary and Amyes Tim Audio Post Production for Television and Film: An introduction to technology and techniques [Book] = Audio Post Production for Television and Film. - Oxford : Focal Press, 2007. - 3rd Edition. 7. REFERENCES Altman Rick Sound Theory / Sound Practice [Book]. - New York : Routledge, 1992. Bartneck Christoph [et al.] Is The Uncanny Valley An Uncanny Cliff? [Conference] // 16th IEEE International Conference on Robot & Human Interactive Communication. - Jeju, Korea : IEEE, 2007. - pp. 368-373. BBC BBC Wild Africa [DVD]. - BBC, 2005. - Episode 2 - Savannah; 00:02:10; 00:35:17. 7