Human Evolution Trends: Cranial Capacity & Tool Use

advertisement

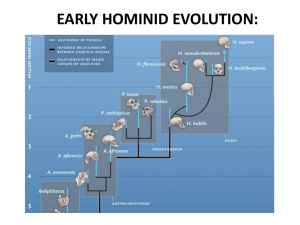

Trends in Human Evolution Excerpts From: Human Evolution The University of Waikato, New Zealand Introduction: Humans are a young species, in geological terms. The average "lifespan" of a mammal species, measured by its duration in the fossil record, is around 10 million years. While hominids have followed a separate evolutionary path since their divergence from the ape lineage (see classification table below), around 7 million years ago, our own species (Homo sapiens) is much younger. Fossils classified as archaic H. sapiens appear about 400,000 years ago, and the earliest known modern humans date back only 170,000 years. Linnaean Classification Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Homo Sapiens (Human) Animalia Chordata Mamalia Primates Hominidae Homo sapiens Pan troglodytes (Common Chimp) Animalia Chordata Mamalia Primates Hominidae Pan troglodytes Examination of hominid remains indicates several trends, including changes in posture, cranial capacity (brain size), and facial angle. Such trends are often misused, e.g. in popular illustrations, to give the impression that evolution has proceeded in a linear manner, from some primitive ancestor through a series of descendants, to culminate in our own species. It's important to remember that the evolutionary history of humans, as of most organisms, is best reconstructed as a bush, where there are often several related species in existence at any one time. Having said that, these trends do give a useful overview of the evolutionary changes that have occurred in our biological history. Trends in cranial capacity Early workers in the field of human evolution expected that the first hominids would have an ape-like physique with a modern cranium. This reflected the attitude that, since our intelligence and large brain size set us apart from all other species, these would be the first human characteristics to evolve. We now know that the actual trend is the reverse of this early expectation. There has been a gradual increase in cranial capacity over the course of human evolution. Thus the early australopithecines had cranial capacities within the range of modern chimpanzees (average around 400cc). Skulls attributed to early Homo begin at around 510cc, and there was a marked increase with Homo erectus, where later specimens had brain sizes of up to 1225cc, well within the modern range. The average cranial capacity of the Neandertals was larger than that of modern humans (1450cc and 1350cc respectively), but this may simply reflect the larger body mass of neanderthalensis. There is a strong positive correlation between body size and brain size, even within species e.g. male humans have larger body mass than females, and correspondingly larger cranial capacity. Equally importantly, the brain size in hominids, particularly Homo species, is greater than would be predicted for animals of their body mass. Trends in general morphology of the skull Dental arcades: in an ape, the teeth are arranged in a rectangular dental arcade, where the left and right cheek teeth are in two parallel lines. Australopith dental arcades tend to be more rectangular than parabolic, but in Homo species the dental arcade is a full parabola, broader at the back than at the front. There is also a strong trend in tooth size, such that the cheek teeth (in particular) of modern humans are smaller than those of australopithecines. Over the last 100,000 years there has been a continuation of the trend towards smaller molar teeth and a more gracile skeleton, such that the Upper Palaeolithic humans of 30,000 years are described as being 20-30% more robust than present-day people. This demonstrable trend in tooth size is probably linked to the use of food-processing techniques that reduce the need for prolonged chewing, and thus provides a good example of the results of natural selection in human populations. Crests and ridges: both the great apes and early hominids have obvious crests and ridges on their skulls. The most obvious are the sagittal and nuchal crests and the brow ridges. Where present, the sagittal crests provide anchorage for large chewing muscles, and are thus most prominent in species where the diet comprises hard, tough material requiring a lot of chewing. Brow ridge development in hominids may also be related to diet, as large brow ridges help to redirect the considerable stresses placed on the skull by a diet of coarse vegetable matter. There is a general trend towards a flatter facial angle with the appearance of more recent hominids, culminating in the vertical face of Homo sapiens. Note, though, that there is considerable variation even among the older members of our lineage. Bipedalism: Bipedalism appeared very early in our evolutionary history. Until recently there was disagreement over the posture of Sahelanthropus (c. 7 million years ago). However, a computer-assisted reconstruction of this fossil shows a foramen magnum beneath the cranium, and relatively small nuchal crest, indicating that this species was bipedal, although not fully erect in posture (Zollikofer et at. 2005). In contrast, Homo erectus was possibly an even more efficient biped than modern humans, due to the narrower pelvic outlet in erectus. The wider pelvic outlet in sapiens, an adaptation permitting the birth of large-brained infants, places the hip joints further apart than required for optimum locomotory efficiency. (This is a good example of how evolution produces compromise solutions, rather than perfection.) Reduced sexual dimorphism: All hominoids show some differences in size between the sexes, as well as in such features as the shape of the pelvis and in crests on the skull. Thus male gorillas weigh perhaps twice as much as females. This size difference is much less in chimpanzees and even less pronounced in modern humans, where on average males are 1.2 times as heavy as females. This trend towards a lesser degree of sexual dimorphism can be traced in hominin fossils. The skeletons of the australopithecines show a marked degree of sexual dimorphism, which is reduced in the early hominids. Tools and Tool Use: At present the earliest-known evidence of the manufacture and use of tools comes from a 2.5 million-year-old site, possibly associated with Australopithecus garhi. This site contains primitive stone tools, but no hominin remains. Animal bones recovered together with garhi remains, from a nearby site of the same age, appear to show cut marks from stone tools. These tools predate the better-known Oldowan tool culture associated with Homo habilis. These are often described as "cobble tools", and comprise two main types, core tools and flake tools. Core tools are stones with one or more flakes knocked off one end to give a jagged edge. Flake tools are the flakes removed in producing core tools, and were not modified any further before being used. The Oldowan tool culture persisted in Africa for almost a million years. With Homo erectus came the more sophisticated Acheulean toolkit. These tools were more highly modified than the earlier cobble and flake tools, with sharper and straighter edges formed by careful removal of more and smaller flakes. Perhaps the best-known Acheulean tool is the so-called hand axe, a teardrop-shaped implement with a pointed end and sharp sides. We have no way of knowing just how these hand axes were used, but they were probably put to a wide range of uses. Other Acheulean tools included hammers, cleavers, and flake-based tools such as knives (probably held directly in the hand, rather than hafted to a handle). Erectus was probably the first hominin to leave Africa. Acheulean tools are found in both Europe and Asia. Until recently it was believed that Chinese erectus populations continued to use Oldowan tools, but Acheulean tools dating back 1.3 million years were found in China in 2001. Along with more sophisticated tools came a change in the foods eaten, and how these foods were obtained. While the australopithecines, and perhaps H. habilis , were essentially vegetarian, meat was a regular part of the erectus diet. Remains from many sites, including Zhoukoudian in China, show that erectus was eating meat on a large scale and from a range of animal species, in addition to a wide variety of plant foods. These animals may have been both scavenged (from other predators) and hunted. The year-round availability of calories from meat would have made it possible for erectus to move from its tropical homeland into temperate regions. Parts of China, for example, experience cold winters, when fresh plant foods are not readily available and meat would be the primary source of calories. There is also a possible causal link between the marked increase in cranial capacity of Homo erectus especially the rapid rate of growth of the brain after birth - compared to its predecessors, and the regular presence of meat in erectus diets. The brain is a very fatty organ, and meat is a much better source of the necessary fats than plant foods. The high calorie content of meat is also important, as the brain is a very energy-hungry organ. (And of course, breastfeeding an infant with a rapidly growing brain is energetically very expensive.) Another leap in tool development came with the Mousterian tool culture, associated with both Neandertals and archaic Homo sapiens. In a significant advance over the Acheulean culture, a stone core was carefully shaped before flakes were struck off it: different core shapes gave different flakes. These flakes could then be further modified for a range of different tasks, and some have a tang at the end that suggested that they were hafted to a wooden or bone handle. The appearance of modern Homo sapiens saw further innovation with a new group of tool-making styles, collectively known as the Upper Palaeolithic industry. The earliest such tools date from Africa, around 90,000 years ago. Other cultural artifacts are associated with the later Gravettian, Solutrean, and Magdalenian tool industries. Ivory beads and "Venus" figurines are associated with Gravettian sites, while necklaces, animal figurines, and symbolic art appeared during the Magdalenian, 18,000 to 12,000 years ago. Language & Culture: This hard evidence of human cultural evolution can be used to infer something about the nature of the human societies producing these artifacts. Needles suggest the manufacture of relatively sophisticated clothing, as does the use of huge quantities of beads to decorate these clothes (found in some grave sites). Palaeoanthropologists have linked the nature of many cave paintings and carvings to the development of various rituals - and also to the development of fluent abstract language. They argue that the complex and often abstract nature of much cave art could not have been developed without an equal ability to communicate. Similarly, the appearance of complex burials at some Upper Palaeolithic sites may imply concerns or beliefs about an afterlife. We think of complex culture as a hallmark of humanity. However, art works, such as jewellery, carving, and cave paintings do not appear in the record until 30-40,000 years ago. This follows the development of the extremely sophisticated Aurignacian tool kits associated with Cro-Magnon culture. Some scientists suggest that the use of highly sophisticated language accompanied this flowering of culture. This is not to say that earlier humans, and hominids, were not capable of speech. A Selection of Hominids: Australpithecus afarensis: The best-known member of this species is "Lucy" , discovered in 1974 by Don Johanson & Tom Gray and estimated to be around 3.2 million years old (afarensis lived from 3.9 to 3 million years ago). She is named for a song playing on the radio during the celebration of her discovery: Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. Afarensis remains indicate that the species was strongly sexually dimorphic, which may give us some clues about social behaviour in afarensis, since modern apes with a high degree of sexual dimorphism are polygynous. The face and cranium of afarensis was ape-like; the teeth are intermediate between ape and human. Australopithecus garhi: Its discoverers felt could be intermediate between A. afarensis & early Homo, was described in 1999 from fossils found in the Awash region of Ethiopia. The 2.5 million-year-old fossils were found in association with animal bones - which had marks on them that appeared to be from stone tools. Very simple stone tools were found in a nearby site of the same age. Homo habilis: lived from 2.4 until 1.5 million years ago, and closely resembles the australopithecines. In fact, recent papers have suggested that habilis would be more appropriately classified in Australopithecus. The face still projects forwards but the facial angle is less than in A. africanus. Average cranial capacity in habilis is about 650cc, and the range is 500 800cc - this overlaps both the australopithecines (at the lower end) and H. erectus (at the upper limit). Analysis of wear patterns on the teeth suggest that habilis was adding meat to its diet probably as a scavenger as there is no evidence that hunting was a common practice. Homo erectus: lived between 1.8 million and 300,000 years ago, and was probably the first hominid species to move out of Africa and colonize Europe and Asia. This significant event must have happened early in the species' history, as fossils that may belong to erectus but which are dated at around 1.8 million years ago have been found in Dmanisi, Georgia. Erectus had a long, low skull, with little forehead and a cranial capacity of between 750 and 1225cc. The smaller brain sizes are associated with older specimens. The face had a projecting lower jaw that supported large molar teeth but lacked a chin. This was the first hominid to have a projecting, rather than a flattened, nose. The post-cranial skeleton of Homo erectus was robust, suggesting they were stronger than modern humans. Members of this species, at least in Africa, were tall; some estimates place them in the upper quartile of the height range for H. sapiens. However, the few remains from China ("Peking man") are from shorter individuals. This probably reflects adaptation to the local climate. Tall, slender individuals are well adapted to lose heat in hot climates, as their bodies have a high surface area to volume ratio (SA:V). Those living in colder regions need to conserve heat, and heat loss is reduced in short, stocky individuals with a lower SA:V. Homo neanderthalensis: Neanderthals lived between 230,000 and 30,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, and were found only in Europe and the Middle East, where they coexisted with modern humans for the later part of their existence. This species gets its name from the Neander valley, or Tal, in Germany, where the type specimen was found in 1856. All Neanderthals are heavily built but those from Western Europe are particularly robust. Their heavy physique was probably an adaptation to the extremely cold conditions in which they lived. Recent genetic studies support the hypothesis that Neanderthals and early humans interbred. Homo sapiens (modern): A recent find provides good evidence that the earliest known recognizably modern humans lived in Africa, around 160,000 years ago. These fossils come from Herto, in the Middle Awash of Ethiopia (White et al. 2003). The fact that the Herto fossils are so old supports the argument that fully modern humans first arose in Africa, later migrating into Europe & Asia to displace the other hominid species already living there (the "out of Africa" hypothesis). The average cranial capacity of modern humans is around 1350cc, with a range for normal individuals of from 800 to close to 2000cc. The brain is enclosed in a high, vaulted skull with a high forehead, and brow ridges are absent or, if present, very small. The relatively delicate jaw has small teeth and a prominent chin, and the post-cranial skeleton is gracile. Excerpts From: Human Evolution: http://sci.waikato.ac.nz/evolution/HumanEvolution.shtml#Trendsinhumanevolution The University of Waikato, New Zealand; Lexile 1400 CIS Unit Trends in Human Evolution (9th and 10th grade Biology) SC.912.L.15.10: Identify basic trends in hominid evolution from early ancestors six million years ago to modern humans, including brain size, jaw size, language, and manufacturing of tools. Essential Questions: o What are some basic trends in hominid evolution? o What is the taxonomic classification of man? CIS Lesson Trends in Human Evolution 1. Hook Engage: Finding Lucy http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/library/07/1/l_071_01.html 2. Question #1 Predict whether human evolution is best reconstructed in a linear manner (e.g., from some primitive ancestor through a series of descendants, to culminate in our own species) or if it is best reconstructed as a bush, where there are often several related species in existence at any one time. 3. Distribute article. 4. a. b. c. d. e. Pre-teach vocabulary: Australopithecine Cranial/cranium Culminate Dental arcade Foramen magnum f. g. h. i. j. gracile Hominid Hominin Hominoids Morphology k. Neanderthal l. Nuchal crest m. Sagittal crest 5. Text-marking: A = Appearance B = Behavior 6. Question #2 Construct at least one paragraph explaining why human evolution is best reconstructed as a bush and not linearly as previously believed. In your response, be sure to provide examples of overlapping species and characteristics they may or may not share with one another. 7. Note-taking: Guiding question “What are the major trends in human evolution?” Identify the species for which they are associated and the relative time period for their appearance or disappearance. 8. Task #3 You have been commissioned to create a product that details the trends in human evolution. You may create a graphical timeline, digital storyboard, PowerPoint, or webpage. For each species, along with a picture, construct at least one associated paragraph that details the physical and behavioral characteristics of that species along with the time period in which that species lived. For each species, provide information on the major trends as they existed in that species and how it evolved from earlier species. The major trends to note are: changes in the morphology of cranium and skull, bipedality, sexual dimorphism, tool use, and language & culture. #1 Predict whether human evolution is best reconstructed in a linear manner (e.g., from some primitive ancestor through a series of descendants, to culminate in our own species) or if it is best reconstructed as a bush, where there are often several related species in existence at any one time. #2 Construct at least one paragraph explaining why human evolution is best reconstructed as a bush and not linearly as previously believed. In your response, be sure to provide examples of overlapping species and characteristics they may or may not share with one another. Directed Note-Taking Trends in Human Evolution Directions: Record notes containing the most important information relevant to the guiding question. Guiding Question: “What are the major trends in human evolution?” Identify the species for which they are associated and the relative time periods for their appearance or disappearance. Check Relevant Categories Page/ Paragraph# Notes Species Trend in Evolution Collaborative Work: After completing your chart, be prepared to compare your notes with others. Time Period Additional Notes Page Page/ Paragraph# Notes Species Trend in Evolution Time Period Question Generator Directions: Carefully review the text for words, phrases or statements that create questions in your mind. Discuss these questions in your group, and then document your group’s questions below. Trends in Human Evolution Do your questions pertain to any of the categories on the right? If yes, place a check in the appropriate box. Page/ Paragraph# Notes Collaborative Work: After completing your chart, be prepared to compare your notes with others. Species Trend in Evolution Time Period Directions: Write your response to the following question using information you learned in this unit. You may also use research from additional outside sources. Be sure to cite those sources! #3 You have been commissioned to create a product that details the trends in human evolution. You may create a graphical timeline, digital storyboard, PowerPoint, or webpage. For each species, along with a picture, construct at least one associated paragraph that details the physical and behavioral characteristics of that species along with the time period in which that species lived. For each species, provide information on the major trends as they existed in that species and how it evolved from earlier species. The major trends to note are: changes in the morphology of cranium and skull, bipedality, sexual dimorphism, tool use, and language & culture. Use the space below to begin sketching out your ideas.