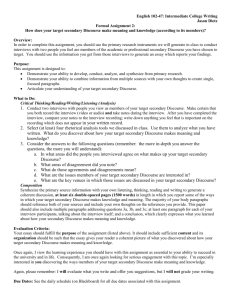

A Foucauldian discourse analysis of The New York Times` portrayal

advertisement