APUSH Reading Liberalism Progressivism Policeman

advertisement

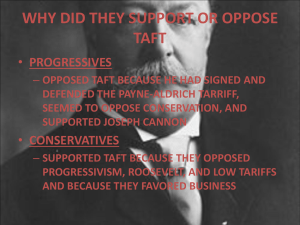

Liberalism: Progressivism #22 Historians often describe the Progressive movement as the urban counterpart to Populism. Although the two movements shared some characteristics, they also had some important differences. Most important, Progressivism found support among small businessmen, professionals, and middle-class urban reformers, in contrast to the disgruntled farmers who fueled the Populist movement. In the end, however, both Progressives and Populists left a lasting stamp on the nation's history. This lecture explores the origins of Progressivism and its impact on American government and society. Some questions to keep in mind: 1. 2. 3. What social, economic, and political factors fostered the Progressive movement? Compare the goals and accomplishments of the Progressives and the Populists. Which movement was more successful? Why might some historians argue that Progressivism was the "Dawn of Liberalism?" Definition of Liberalism: Although many historians speak of a Progressive "movement," we should really think of Progressivism as an umbrella, under which a variety of reform groups and champions of liberalism gathered. So, any discussion of Progressivism should begin with the meaning of "Liberalism" at the beginning of the twentieth century: Government should be more active Social problems are susceptible to government legislation and action Throw money at the problem "Definition" of Progressivism: Progressives, themselves, were never a unified group with a single objective or set of objectives. Instead, they had many different, and sometimes contradictory goals, including: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. End to "white slavery" (prostitution and the sweat shops) Prohibition "Americanization" of immigrants Immigration restriction legislation Anti-trust legislation Rate regulation of private utilities Full government ownership of private utilities Women's suffrage End to child labor Destruction of urban political machines "Taylorism" Political reform Types of Progressive Reform There were four basic types of Progressive reform, and each reform corresponded to a key word, repeated time and again in the rhetoric of Progressives: Economic--"Monopoly" Structural and Political--"Efficiency" Social--"Democracy" Moral--"Purity" Basic Goals of Progressives Even though they were not a unified group, Progressives shared five basic characteristics or beliefs: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. They were moralists Government, once purified, must act Believed in protecting the weakest members of society Never challenged capitalism's basic tenets Paternalistic, moderate, soft-minded Origins of Progressive Thought and Action: 1. "Discovery" of poverty Poverty had always existed in American society, but a number of urban reformers began to call for new legislation to help the poor in the late 1870s and early 1880s . An entirely enclosed court in a tenement district in Baltimore 2. Charity movement Prior to the late 1870s, there was no systematic method for social welfare, just individual charity groups funded by private donors. In 1877, however, reformers in Buffalo, New York, organized a citywide effort to coordinate local charities. This type of system eventually spread to other United States cities. 3. Emancipation of Women The 1880s saw the first generation of women--mostly white and middle- or upper-class--to graduate from college in large numbers. These women left college full of enthusiasm, but, for the most part, were shut out of professions in medicine, law, science, and business. So, they often used their energies to battle social injustices. 4. The "Social Gospel Movement" Up until the 1880s, most Protestant ministers had not concerned themselves with the problems of industrial society. Rapid urbanization and industrialization, however, convinced many of them to fight for social justice. The goal of the Social Gospel movement was to make Christian churches more responsive to social problems like poverty and prostitution. Some ministers became known nationally as spokesmen for the Social Gospel, including Washington Gladden and Walter Rauschenbusch. 5. Social settlement movement: The social settlement movement was formed as a ministry to immigrants and the urban poor. Universityeducated men and women (such as Jane Addams) settled in working-class neighborhoods to try and help the poor and learn about the real world. Most settlement houses started with clubs and classes, then campaigned for housing and labor reform. As they aided people, settlement houses also tried to instill middle-class values and often had a paternalistic attitude toward the poor. Immigrant children at Jane Addams' Hull House in Chicago 6. Good Government movement In the 1880s, reformers organized clubs in several American cities in an effort to streamline government, to clean up corruption, and to turn municipalities into model corporations. The National Conference for Good City Government took place in Philadelphia in 1894. This was the starting point for many reformers who identified themselves with the Progressive movement. The keynote speaker was future President Theodore Roosevelt, who was the Chief of Police for New York City at the time. In his speech, Roosevelt preached morality and efficiency in city government. The founding of the National Municipal League was one crucial outcome of the National Conference for Good City Government. The League was a training ground for Progressives. It became an exchange network for various reform movements and still exists today. Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt (18581919)--A Republican champion of "trust-busting" and conservation, Roosevelt served as vice president under President William McKinley and became president when McKinley was assassinated in 1901. Roosevelt was reelected in 1904, but did not seek a third term in 1908. In his place, the Republican convention nominated as its presidential candidate William Howard Taft, who promised to carry on Roosevelt's policies. In 1912, feeling that Taft, had undermined his progressive legacy, Roosevelt sought, but did not get, the Republican nomination. As a result, he ran for president as the candidate of the Progressive Party. With the Republican vote split between Taft and Roosevelt, Democrat Woodrow Wilson won the 1912 presidential election. Campaign poster for William McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt Bull Moose Party--Nickname for the Progressive Party of 1912. The bull moose was the emblem for the party, based on Roosevelt's boasting that he was "as strong as a bull moose." William Howard Taft (1857-1930)--Republican President of the United States from 1909 to 1913. The United States' most corpulent chief executive, Taft stayed close to the policies of Roosevelt at the beginning of his term. Later in his presidency, however, Taft favored conservative measures, such as a high protective tariff, and lost popularity. Postcard states "Here's to the Man the New Dixie Counts On" Robert M. "Fightin' Bob" LaFollette (1855-1925)-Progressive Era political leader who served as a United States Congressman from 1885 to 1891, governor of Wisconsin from 1900 to 1905, and United States Senator from 1905 to 1925. In 1924, LaFollette ran as an independent Progressive candidate for President and polled nearly 6 million votes out of some 30 million cast. Robert M. La Follette (1855-1925) speaking before an audience of 12,000 in Los Angeles, 1907 Robert "Fighting Bob" La Follette (1855-1925) in a classic pose Copyright 1997 State Historical Society of Wisconsin Ultimately, Progressives introduced a host of reforms and transformed the way that many Americans understood government and economics. Progressivism, however, did not just transform domestic life. As the United States stepped onto the world stage in the early twentieth century, it also shaped the nation's foreign policy. The Progressive Movement and National Politics TR is "Dee-Lighted" to throw his hat into the ring of the 1912 presidential election Copyright 1997 State Historical Society of Wisconsin The Policeman of the World In 1898, America, which was becoming an ever more important player in world affairs, entered into its first international conflict--the Spanish-American War. A series of wars and police actions followed in the twentieth century, from World War I to Afghanistan. Why did American leaders begin to believe that the United States had a right and a duty to police the world? This lecture examines trends of expansionism and imperialism in the period after the Civil War, trends which still influence American foreign policy today. Some questions to keep in mind: 1. 2. In the late-nineteenth century, was the United States essentially isolationist, essentially expansionist, or a combination of both? What were the economic and political consequences of religious missionary work in the nineteenth century? The following three general propositions form the foundation of our future discussions about war and foreign policy: 1. 2. 3. War is the extension of a nation's diplomacy by other than peaceful means. For whatever reasons a nation enters a war, that war, itself, changes the relationship of its citizens with each other and with the national government. The rhetoric that justifies or opposes a war reveals a great deal about the way a nation's citizens think about themselves. Historians have opposing interpretations of America's involvement in world affairs in the years after the Civil War: 1. 2. 3. Before 1898, America was isolationist After the Civil War, America was expansionist. America was isolationist in theory, expansionist in practice. To decide which of these interpretations is more accurate, we must examine three major trends of the time from the isolationist and the expansionist points of view: 1. 2. 3. Industrial expansion Western settlement Growth of the federal government Those who believed that America was basically isolationist before 1898 contend that these three domestic concerns prevented the United States from becoming involved in foreign affairs. In their viewpoint, the United States could not devote much time or energy to foreign affairs. Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) was President from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. In his inaugural address in 1885 he summed up America's isolationist doctrine: "A policy of peace, commerce and honest friendship with all nations; entangling alliances with none." Now let us examine The Rest of the Story. Those who argue that America was expansionist after the Civil War maintain that these same three domestic concerns actually led the United States to extend its global interests. Industrial expansion From 1865 to 1890, the industrial complex of the United States expanded rapidly and the nation became one of the world's two great industrial powers. American industrialists looked for new markets in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Four aspects of industrial expansions also affected imperialist tendencies: Business cycles. Alternating cycles of prosperity and recession (and even economic depressions in 1873 and 1893) meant that production of American goods often exceeded consumption. International investment capital. Between the late 1860s and the turn of the century, foreign concerns invested $3 billion in the nation's economy. Desire to expand markets. Shift in balance of trade. For example, Standard Oil had few petroleum exports in 1880, but controlled 70% of the world's oil market by 1890. Kimberly-Clark paper mill in Wisconsin (in Appleton, Kimberly, Neenah, or Niagara) Copyright 1997 State Historical Society of Wisconsin Western settlement Recall that farmers settled and tilled more and more land in the West, in part, because of the existence of seemingly boundless international markets. As European demand for United States agricultural surplus declined from 1880 on, farmers had to seek new markets in order to survive. Growth of federal government Increasingly, the federal government made policies on economic matters, such as import tariffs and currency reform, and helped pave the way for American commercial expansion abroad. Industrialists and farmers, alike, turned to the federal government for help in securing new markets. William Evarts--United States. Secretary of State from 1877 to 1881. In his "Report upon the Commercial Relations of the United States" Evarts argued that the government should foster economic growth. He revitalized the consular service in foreign countries and appointed successful businessmen as consuls to represent America's interests in foreign countries. Card from Singer Mfg. Co.'s series depicting life in countries importing Singer sewing machines Copyright 1997 State Historical Society of Wisconsin "Pork Diplomacy" of the 1880s demonstrates the growing correlation between business and government. In the 1870s American farmers "were turning out pigs like they were going out of style" (Prof. Schultz) and were exporting their surplus pork to Europe. In the 1880s, because of protest from French and German farmers, these governments passed restrictions on the importation of American pork. The nation's farmers and businessmen were outraged and the United States government brought economic reprisals against the German states and France. Hog Copyright 1997 State Historical Society of Wisconsin Prize-winning hogs, 1884 Copyright 1997 State Historical Society of Wisconsin The "Missionary Factor" Missionaries of Peace After the Civil War, the pace of American Christian missionary work around the globe, especially in Asia and Africa, increased dramatically. 1. Soul saving and profit making go hand-in-hand. For example, the founder of the 2. 3. Dole pineapple fortunes was the son of a missionary to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii). Many other American businessmen learned about potential foreign markets from reports that missionaries brought back. Government protection and international agreements. The federal government had a long-standing policy of protecting the needs of its citizens in foreign lands. More American missionaries around the world meant more American citizens to protect from discrimination and attack, so the government was drawn into "entangling alliances" with other countries. A faith in the destiny of Christianity to conquer the world. Political cartoon: "What the United States Has Fought For" Copyright 1997 State Historical Society of Wisconsin Robert E. Spear was the head of the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church. In one of his speeches, he claimed: "The civilized nations are beginning to perceive that they have a duty, which is often contemptuously spoken of, to police the world. The recognition of this duty has been forced by trade." Missionaries of War By the 1880s, the once-respectable United States Navy was in shambles. Three factors allowed for its renewal and development: 1. The economic recovery from the Depression of 1873 meant that the federal 2. 3. government now had surplus money to build a modern navy. William Hunt became the first truly effective Secretary of the Navy. Many Americans realized that the United States was a 10th-rate naval power essentially unprepared if commercial rivalries turned into military conflict. Even landlocked Populists in the Midwest campaigned for a larger navy. There was a widelyheld belief that the nation needed ships, not to make war, but to protect its rights and prestige. Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) was a naval strategist, historian, and leading advocate of a powerful American navy who influenced the thinking of Teddy Roosevelt and other government leaders. In his writings and speeches, Mahan stated: 1. Surplus production requires commercial colonies 2. Oceans should be highways, not barriers 3. A powerful navy is essential for commerce Mahan believed in the power of a modern military to prevent war, and wrote: "War now not only occurs more rarely, but is an occasional excess, from which recovery is easy." **Justification for Imperialism: Champions of expansionism often justified American imperialism in terms of American DESTINY and American DUTY. Frederick Jackson Turner (1861-1932) wrote "The Significance of the Frontier in American History" (1893), which argued that the nation's western frontier had promoted American democracy. Some American intellectuals expanded on Turner's thesis and argued that expansion overseas was the next great frontier that would help reinvigorate the nation and its political system. Woodrow Wilson was a friend and advocate of Turner who tried to put Turner's writings into practice once he reached the White House. The "Anglo-Saxon myth" was the dominant intellectual justification for American imperialism. This myth held that the Anglo-Saxons were the final result of cultural evolution. The United States, as the obvious seat of growing Anglo-Saxon power, had a duty to expand its influence throughout the world. The two prevalent themes of American DESTINY and American DUTY are best summed up in the writings of Senator Albert J. Beveridge (1862-1927) of Indiana. A historian as well as a politician, Beveridge stated in his 1898 speech, "The March of the Flag:" "Will you remember today, that we but do what our fathers did. We but pitch the tents of liberty further westward, further southward. We only continue the march of the flag. The question is not an American question but a world question. Shall free institutions broaden their blessed reign? The opposition to expansion tells us we ought not to govern a people without their consent. I answer that the rule of liberty applies only to those who are capable of self-government. Do we owe no duty to the world? Wonderfully has God guided us. It is ours to set the world its example of right and honor. We cannot fly from our world duties. It is ours to execute the purpose of a fate that has driven us to be greater than our small intentions. We cannot retreat from any soil where Providence has unfurled our banner. It is ours to save that soil for liberty and civilization. For liberty and civilization and God's promises fulfilled, the flag must henceforth be the symbol and the sign to all mankind." This faith in destiny, duty and the morality of power would be played out in military expansion and war during the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.