DOCX - Department of Psychology

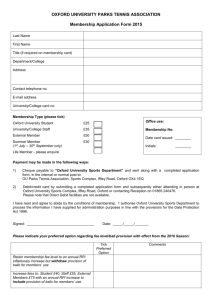

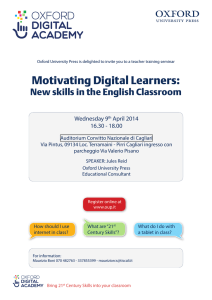

advertisement