Name: Date: Hour: Directions

advertisement

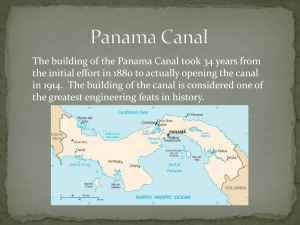

Name: Date: Hour: Directions: Read the text section by section Highlight the main ideas/key facts for each section For each section place a * next to the following: Who, What, Where, When, Why and How. 7 Fascinating Facts about the Panama Canal By Elizabeth Nix August 15, 2014 August 15, 1914, marks the 100th anniversary of the official opening of the Panama Canal, the American-built waterway across the Isthmus of Panama that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The 50-mile-long passage created an important shortcut for ships; after the canal was constructed, a vessel sailing between New York and California was able to bypass the long journey around the tip of South America and trim nearly 8,000 miles from its voyage. The canal, which uses a system of locks to lift ships 85 feet above sea level, was the largest engineering project of its time 1. The idea for a canal across Panama dates back to the 16th century. In 1513, Spanish explorer Vasco Nunez de Balboa became the first European to discover that the Isthmus of Panama was just a slim land bridge separating the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Balboa’s discovery sparked a search for a natural waterway linking the two oceans. In 1534, after no such passage across the isthmus had been found, Charles V, the Holy Roman emperor, ordered a survey to determine if one could be built, but the surveyors eventually decided that construction of a ship canal was impossible. 2. The men behind the Suez Canal and Eiffel Tower were convicted in connection with failed effort to build a canal. In the ensuing centuries, various nations considered developing a Panamanian canal but a serious attempt wasn’t made until the 1880s. In 1881, a French company headed by Ferdinand de Lesseps, a former diplomat who developed Egypt’s Suez Canal, began digging a canal across Panama. The project was plagued by poor planning, engineering problems and tropical diseases that killed thousands of workers. De Lesseps intended to build the canal at sea level, without locks, like the Suez Canal, but the excavation process proved far more difficult than anticipated. Gustave Eiffel, who designed the famous tower in Paris that bears his name, was then hired to create locks for the canal; however, the De Lesseps-led company went bankrupt in 1889. At the time, the French had sunk more than $260 million into the canal venture and excavated more than 70 million cubic yards of earth. The canal venture’s collapse caused a major scandal in France. De Lesseps and his son Charles, along with Eiffel and several other company executives, were indicted on fraud and mismanagement charges. In 1893, the men were found guilty, sentenced to prison and fined, although the sentences were overturned. After the scandal, Eiffel retired from business and devoted himself to scientific research; Ferdinand de Lesseps died in 1894. That same year, a new French company was formed to take over the assets of the bankrupt business and continue the canal; however, this second firm soon abandoned the endeavor as well. 3. America originally wanted to build a canal in Nicaragua, not Panama. Throughout the 1800s, the United States, which wanted a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific for economic and military reasons, considered Nicaragua a more feasible location than Panama. However, that view shifted thanks in part to the efforts of Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla, a French engineer who had been involved in both of France’s canal projects. In the late 1890s Bunau-Varilla began lobbying American lawmakers to buy the French canal assets in Panama, and eventually convinced a number of them that Nicaragua had dangerous volcanoes, making Panama the safer choice. In 1902, Congress authorized the purchase of the French assets. However, the following year, when Colombia, which Panama was then a part of, refused to ratify an agreement allowing the United States to build a canal, the Panamanians, with encouragement from Bunau-Varilla and tacit approval from President Theodore Roosevelt, revolted against Colombia and declared Panama’s independence. Soon afterward, U.S. Secretary of State John Hay, and Bunau-Varilla, acting as a representative of Panama’s provisional government, negotiated the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, which gave America the right to a zone of more than 500 square miles in which it could construct a canal; the Canal Zone was to be controlled in perpetuity by the Americans. All told, the United States would shell out some $375 million to build the canal, which included a $10 million payment to Panama as a condition of the 1903 treaty, and $40 million to buy the French assets. A century after the United States completed the Panama Canal, a navigable link across Nicaragua remains a possibility: In 2013, a Chinese company announced it had struck a $40 billion deal with the Nicaraguan government for the rights to construct such a waterway. 4. More than 25,000 workers died during the canal’s construction. The canal builders had to contend with a variety of obstacles, including challenging terrain, hot, humid weather, heavy rainfall and rampant tropical diseases. The earlier French attempts had led to the deaths of more than 20,000 workers and America’s efforts fared little better; between 1904 and 1913 some 5,600 workers died due to disease or accidents. Many of these earlier deaths had been caused by yellow fever and malaria; diseases that the medical community at the time believed were caused by bad air and dirty conditions. By the early 20th century, however, medical experts better understood the role of mosquitoes as carriers for these diseases, allowing them to significantly reduce the number of deaths among canal workers, thanks to a host of sanitation measures that included draining areas with standing water, removing possible insect breeding grounds and installing window screens in buildings. 5. Between 13,000 and 14,000 ships use the canal every year. American ships use the canal the most, followed by those from China, Chile, Japan, Colombia and South Korea. Every vessel that transits the canal must pay a toll based on its size and cargo volume. Tolls for the largest ships can run about $450,000. The smallest toll ever paid was 36 cents, plunked down in 1928 by American adventurer Richard Halliburton, who swam the canal. Today, some $1.8 billion in tolls are collected annually. On average, it takes a ship 8 to 10 hours to pass through the canal. While moving through it, a system of locks raises each ship 85 feet above sea level. Ship captains aren’t allowed to transit the canal on their own;, a specially trained canal pilot takes navigational control of each vessel to guide it through the waterway. In 2010, the 1 millionth vessel crossed the canal. 6. The United States transferred control of the canal to Panama in 1999. In the years after the canal opened, tensions increased between America and Panama over control of the canal and the surrounding Canal Zone. In 1964, Panamanians rioted after being prevented from flying their nation’s flag next to a U.S. flag in the Canal Zone. In the aftermath of the violence, Panama temporarily broke off diplomatic relations with the United States. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter and General Omar Torrijos of Panama signed treaties that transferred control of the canal to Panama in 1999 but gave the United States the right to use military force to defend the waterway against any threat to its neutrality. Despite opposition by a number of politicians who didn’t want their country to give up its authority over the canal, the U.S. Senate ratified the Torrijos-Carter Treaties by a narrow margin in 1978. Control of the canal was transferred peacefully to Panama in December 1999, and the Panamanians have been responsible for it ever since. 7. The canal is being expanded to handle today’s megaships. In 2007, work began on a $5.25 billion expansion project that will enable the canal to handle post-Panamax ships; that is, those exceeding the dimensions of so-called Panamax vessels, built to fit through the canal, whose locks are 110 feet wide and 1,000 feet long. The expanded canal will be able to handle cargo vessels carrying 14,000 20-foot containers, nearly three times the amount currently accommodated. The expansion project, expected to be completed in late 2015, includes the creation of a new, larger set of locks and the widening and deepening of existing navigational channels. However, while the new locks will be able to fit many modern ships, they still won’t be super-sized enough for some vessels, such as Maersk’s Triple E class ships, the planet’s biggest container ships, which measure 194 feet wide and 1,312 feet long, with a capacity of 18,000 20-foot containers. Did You Know? Some 52 million gallons of fresh water are used each time a ship makes a trip through the Panama Canal. The water comes from Gatun Lake, which was formed during the canal’s construction by damning the Chagres River. With an area of more than 163 square miles, Gatun Lake was once the world’s largest made-man lake. Panama Canal Questions-Answer in complete sentences using details from the text. 1) What is an Isthmus? Why would the Isthmus of Panama be considered an important strategic place? 2) How did the canal engineers use their knowledge of geography and science to overcome the challenges of building the canal? What happened to the original French builders that started the canal? 3) What were the major causes of death for the canal workers? How did they fix these problems? 4) How did the USA get the canal? What events occurred as a result of the USA’s actions? Why was it so important to the USA to control the canal? Why is the USA no longer in charge? How will giving over control impact the USA? 5) What counties use the canal the most? What do these countries have in common? How might this change? 6) How does the canal make money? How much money does the canal currently make? How much will it cost to expand the canal? Based on the money the canal makes now is expanding it worth the effort (support your answer)?