Plankton- Food For All

advertisement

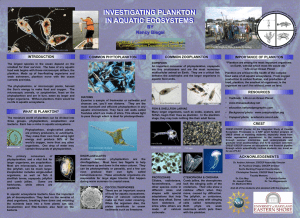

Plankton- Food For All Plankton is the foundation of the ocean food web. The word plankton comes from the Greek word "planktos" which means drifting. Plankton are comprised of many small organisms- protists, larva of invertebrates (animals), etc. One of the most important organisms in the whole ocean is also the smallest. Phytoplankton are organisms that float on or near the surface of the water. Most are rounded and singlecelled. All phytoplankton use photosynthesis for their energy, but some get additional energy by consuming other organisms. The most common phytoplankton are diatoms and dinoflagellates. Diatoms are single-celled algae. They often join together in long chains. Dinoflagellates are small organisms with two tails or flagella. Dinoflagellates come in all kinds of shapes and sizes. Some have shells and some don't. Not all dinoflagellates rely only on photosynthesis for all their energy. Some wrap themselves around food and absorb it. Some dinoflagellates can make light using bioluminescence. Phaeophyta or brown algae are another type of phytoplankton. Blue-green algae or cyanobacteria are also phytoplankton, although they are very unique. They photosynthesize, but some also use nitrogen for their energy. They are nitrogen fixers. They change free nitrogen into nitrates which are used by the cyanobacteria and by other plants in the ocean. Phytoplankton are the base of the ocean's food web and are the food source for zooplankton. Zooplankton are ocean animals that don't swim at all or are very weak swimmers, and they drift or move with ocean currents. They can be found in the sunlit zone and in deep ocean waters. Zooplankton range in size from tiny microbes to jellyfish, although most zooplankton are tiny, single-celled organisms. There are two types of zooplankton. Permanent or holoplankton will always be zooplankton. Temporary or meroplankton are made up of the larvae of fish, crustaceans and other marine animals. If they survive, they will grow into nekton or free-swimming organisms. Warming Oceans Will Play Major Role In Less Phytoplankton Diversity Phytoplankton, organisms that exist in the sunlit layer of the world’s oceans, are important for the sustainability of the aquatic food web. However, future warming oceans could significantly alter the populations of these important organisms, further impacting climate change. Since phytoplankton play a major role in the food chain and the world’s carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous cycles, a significant decline in numbers could have unequivocal consequences for not just the world’s oceans, but for the entire planet. As the oceans heat up, more of these organisms will thrive around polar waters and less so in the tropics and equatorial waters. “In the tropical oceans, we are predicting a 40 percent drop in potential diversity, the number of strains of phytoplankton,” said study coauthor Mridul Thomas, a biologist at MSU. “If the oceans continue to warm as predicted, there will be a sharp decline in the diversity of phytoplankton in tropical waters and a poleward shift in species’ thermal niches–if they don’t adapt.” “The research is an important contribution to predicting plankton productivity and community structure in the oceans of the future,” said David Garrison, program director of the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Division of Ocean Sciences, which co-funded the study along with NSF’s Division of Environmental Biology. “The work addresses how phytoplankton species are affected by a changing environment, and the really difficult question of whether adaptation to these changes is possible,” Garrison said in a press release. Thomas and his colleagues said that since phytoplankton play a key role in regulating atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, and therefore the climate of the world, any mass shift in populations could spell trouble for further climate change. Water temperatures strongly influence growth rates. While phytoplankton grow much faster in the warmer equatorial waters than do their cold-water counterparts, it is important to observe how increasingly warmer oceans will affect these populations and their ability to consume the world’s carbon. These microorganisms use light, carbon dioxide and nutrients to grow. Although they are small, they flourish throughout the world’s oceans, consuming as much carbon dioxide through photosynthesis as all the terrestrial plants combined. When they die, some sink to the ocean bottom, depositing their carbon in the sediment, where it can be trapped for long periods of time. The scenario is inextricable: phytoplankton rely on a specially acclimatized habitat to thrive, yet human–as well as other–influences on climate have resulted in warming oceans, which could have a potential impact on phytoplanktonic diversity, which in turn could further influence the global climate negatively. “We’ve shown that a critical group of the world’s organisms has evolved to do well under the temperatures to which they’re accustomed,” said study coauthor Colin Kremer, a fellow MSU graduate in plant biology. However, based on ocean temps of the future, many of these microorganisms may not be able to adapt quickly enough to the changes in their environment. Since phytoplankton can’t regulate their temperatures or migrate, they will likely suffer significantly limited growth and diversity, having far-reaching implications for the global carbon cycle, he added. “These results will allow scientists to make predictions about how global warming will shift phytoplankton species distribution and diversity in the oceans,” said Alan Tessier, program director in NSF’s Division of Environmental Biology. “They illustrate the value of combining ecology and evolution in predicting species’ responses.” Being able to forecast the future impact these changes will likely have is a useful tool for scientists around the world, said Garrison in the release. “This is an important contribution to predicting plankton productivity and community structure in the oceans of the future,” he said. “The work addresses how phytoplankton species are affected by a changing environment, and the really difficult question of whether evolutionary adaptation to those changes is possible.” Thomas and Kremer coauthored the research along with MSU faculty members Elena Litchman, zoologist, and Christopher Klausmeier, plant biologist. The research was conducted at MSU’s Kellogg Biological Station.