How to Write a Biography

advertisement

Introduction to Biography

“The best biographies leave their readers with a sense of having all but entered into a second life and of

having come to know another human being in some ways better than [she] knew [herself].

Mary Cable in New York Times, 1969”

(quote found it Notable Women in American History)

A biography is an account of someone’s life which is written by someone other than that person.

Biographies are written as a way to examine and understand a person’s life and importance.

Information comes from primary sources such as diaries, interviews, letters; and secondary

information, such as other biographies, reference books, and histories. While famous and

infamous people are often the subject for biographies, lesser-known people and those who lived

during a specific event can also lend compelling life stories. Biographies are written to examine a

person’s importance and influence, make sense of mysterious or fascinating personalities or

events, and give greater understanding that person’s role in society or history.

Writing a Biography

To begin writing a biography, you need to select a person of interest and decide how you’re

going to present their life. Will you move the reader through the story chronologically or by

moving from one important accomplishment or event to the next? The first step will be to collect

some of the person’s basic facts, such as:

Date of birth/death

Family information

Historical significance

Lifetime accomplishments

Major events in life

Remember, the purpose of writing a biography is not to just recount the basic information, it is to

reveal meaningful aspects of their lives and experiences. This is especially true in the beginning.

You want to grab your writer with your first sentence.

For example, instead of: Toni Morrison was born in Lorain, Ohio on February 18, 1931.

You might begin with: After welding a perfect seam, George Wofford would sign his

name next to it. This habit, combined with having pride for hard work greatly impacted his

second daughter, Chole Wofford, who would later sign her name, now more commonly known

as Toni Morrison, to her award-winning novel, The Bluest Eye. Born in 1931 in Lorain, Ohio, a

town was filled with Europeans, Southern blacks, and Mexicans, Toni would grow…….

Other beginnings might include a letter to or by the subject, a diary entry, or dialogue.

You want to help your readers understand why this person is worth writing about, what about

their experiences makes an interesting story. To do this, you might consider questions such as:

What makes this person special or interesting?

What kind of effect did he or she have on the world and other people?

What are the adjectives you would most use to describe the person?

What examples from their life illustrate those qualities?

What events shaped or changed this person's life?

Did he or she overcome obstacles? Take risks? Get lucky?

Would the world be better or worse if this person hadn't lived? How and why?

Was there something in your subject’s childhood that shaped his/her personality?

Was there a personality trait that drove him/her to succeed or impeded his progress?

What adjectives would you use to describe him/her?

What were some turning points in this life?

What was his/her impact on history?

http://www.infoplease.com/homework/wsbiography.html

http://homeworktips.about.com/od/biography/a/bio.htm

Try to include intriguing and little known facts that help keep your reader interested. For

instance, many know the author of Beloved and first African-American female to win the Noble

Prize in Literature to be Toni Morrison, but in reality, Toni is her nickname, she was born Chloe

and she was not happy when the first publication of The Bluest Eye was printed with Toni

Morrison on the cover. She also was the only student in her first-grade class to enter knowing

how to read. Once you have collected your information and thought about the importance of the

person’s life and experience, begin organizing the information into a story that is coherent and

rich in material that will help your reader gain a greater understanding of the person and their

life.

Sources: http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1993/morrison-bio.html

http://www.math.buffalo.edu/~sww/morrison/morrison_toni-bio.html

http://www.en.utexas.edu/amlit/amlitprivate/texts/morrison1.html

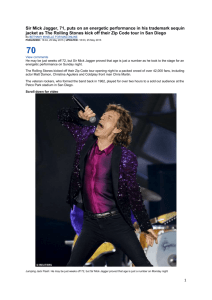

Example of a Biography

“Mick Jagger: Rebel Knight” by Christopher Sandford

Connection

BOAC Flight 505 landed in New York on June 1, 1964. Mick Jagger was first down the steps.

Dressed in jeans and suede jacket, he walked with strides belonging to a man a foot taller,

climbing the great tree of cameras and lights, carrying his own luggage. In the press conference

reporters shouted at him like wild beasts. Bulbs crowded at the platform's edge. "You play ... the

same kind of music ... the same kind of music ... as the Beatles?" Jagger's hair puffed up and

down, his lips pursed. "No." Another journalist swayed towards the stage. "Who's the leader?" A

long pause followed this. More than one individual seemed on the verge of speech. Finally

Jagger came forward, his body so flat that fore looked identical to aft. "We are," he said. "All

ofus." The conference ended and The Rolling Stones were conveyed by Cadillac to the Astor

Hotel. A girl jumped Mick then backed off, hurriedly, like two cats tangling and thinking better

of it. He stared at her open-mouthed, the dark ajar spot forming a hole in his narrow face, before

the police escorted him upstairs.

The colour television spread light through the curtained room. Jagger looked outside:

hundreds of girls (encouraged, it later transpired, by the group's management) were holding

roses, love notes and furry animals, their faces turned upwards like radar dishes among the press.

Media arrangements were elaborate. Jagger seemed to relish the prolonged focus on him, the

drama of delay. An hour late, a second news conference began: "You own a razor?" Jagger

smiled. "Ever use it?" Disarming grin. "How about ... a ... tie?" Through the lobby, smoothly as

if he were being paid, Jagger proceeded to engage, to enchant, obeying his manager's precept to

"under no circumstances, blow it" in New York. As ifin confirmation he merely smiled when

Murray Kaufinan, the celebrated disc jockey, enquired, "You want to lie down?" as, outside, yet

more girls awaited the answer.

Midnight found Jagger in the Peppermint Lounge watching the Younger Brothers

impersonate, among others, Mick Jagger. Girls repeatedly approached him with flowers, gifts

and the information that their parents were out of town; boys, too, gave him a second glance.

Drinks came to the table. Jagger discovered himself having dinner, like looking down into a food

advertisement in a magazine, steaks the size of his head. At one the car appeared - more of a

boat, it seemed to drift through oceans of dust, the pavements cracked from underneath, whole

streets lifted up like crypts in a horror film. At the hotel the girls pounced, the police pushed,

Jagger shuffled in. His feet made funnel-shaped tracks on the scarlet rug. In the suite the

television was still on: Johnny Carson was interviewing Woody Allen. The phone was ringing.

Girls shouted his name. Jagger went to the window as the voices beat up. 'Mick," called

one, "is God."

Jagger smiled, frightening himself.

Down a long concrete corridor, more of a tunnel, The Rolling Stones come up on stage. A

canopy sends down blue light from a wedge of sky, blue scarves hang on balustrades, a film

crew lights up, the group squeezed out by bearded carpenters, electricians, engineers, ritually

late; chaos.

Stage left, draped in yellow breeches, blue kneepads, blue football shirt, Jagger lifts one

foot, rotates, shuffles, legs rail thin, shoulders sloped, his check jacket darting like a shoal of

carnivorous fish. Turning the corner, the clothes seem to precede him by a split second.

He may be the smallest adult ever to wear American football uniform. "How long?" he asks a

man identified as "Roy Lamb - Access All Areas". "How lonng?" His voice is the squeak of a

plastic toy accidentally stepped on.

Lamb ignores him. On the other side of the pink painted curtain the crowd wells up,

70,000 strong, the canopy actually quivering in the communal exhalation. Jagger goes back to

his drill. Up close you can see the waxy shine of make-up. His body seems too slight for the heft

and weight of his head. His mouth looks enormous, the puckered lips sharp in profile. Up comes

a padded knee, little flips of his foot and a head toss. Jagger's mouth gives him the appearance

of pouting even when he isn't. "How long?" he asks, "o Lord?"

This brings a laugh from the man who sits bulky in his coat at the piano. On cue Lamb

looks back to where a bald, bearded man (Alan Rogan - Access All Areas) hands up a guitar,

hangs it and lights a cigarette. Music pumps up, 'Take The 'A' Train', the vaulted interior of the

room starts to shake, a third noise cuts in: "Would you welcome, please ...", Lamb's arm rises,

the curtain flares, the band starts 'Under My Thumb'. Jagger stands there for an instant, eyes

closed, the smallest of the eight figures now on stage. The crowd catches him sullen and still,

like a missionary hauled in front of a court - one whose jurisdiction he doesn't recognise; rigid.

Remote, even. The curtain flaps. At the last second Jagger comes forward, eyes open, darts,

feints, arms pumping and shouts Ello in a voice quite unlike that he uses offstage. Under my

thumb, a bass line rolls, There's a woman, peaks, Who once had me down, and breaks, over and

over, the seven musicians silent and scowling, Jagger pacing left and right, a curious way of

using his free hand, pumping as if coiling a rope. In the guitar break he stamps the stage with his

foot four, five, a dozen times, in the way of a talking horse. He starts to sweat. His eyes hooded.

The lips. Jagger, you notice, is completely impassive as he sings. The motion is all in his arms

and flailing legs - nothing to the face at all. 'Under My Thumb' wells up again, the London of

day-glo, ruffles and Chelsea boots translated to suburban Seattle, 1981. If Jagger has any

nostalgia for this era he artfully conceals it from the crowd, who get only short shouted remarks

like Yeah . .. How you doin'? (a Jagger standard) and, "Here's one for you women" ('Let It

Bleed'). The last is greeted by prolonged silence. Jagger, for all his worldliness (this being his

239th American performance) can still, periodically, get it wrong. For ten minutes he engages in

the sort of bad acting - hamming, snorting, streaming from the flues of his nose only a gifted

actor can produce. He recovers with a quick, hip-grinding 'Start Me Up', then crouches as the

drummer plays 'Miss You', coiled like a half-open blade - or flick-knife. Two more numbers,

Jagger, bare-chested now, howling and kneeing the stage, the bass rolling: the pianist removes

his coat. On the last barthe four standing Stones come forward to give their rendition of a bow.

Jagger stoops. His lips almost brush the stage. As he walks back his face is studiously calm. "Not

bad," he says in a flat, ironic voice. The drummer shrugs. Alan ("Access All Areas") Dunn hands

up a bottle of water. Jagger shuffles backwards on his toes. Two men in suits, one moustachioed,

come forward, their faces wreathed in docile goodwill, beaming volts of excessive charm.

"Great," says one. "Mick."

"Really," the other.

"Sawright," says Jagger. "What's the house?"

"Seventy-two five ... times 16" - he taps his briefcase, flat as a wafer -"plus outside, we're

looking at two, maybe three."

In other words a quarter of a million dollars. As Jagger grunts, Dunn falls on him with a

kind of luminous cape; it turns out to comprise the American and British flags. "Satisfaction," he

says cryptically. "Now."

Jagger stands there, a half-naked man wearing a cloak talking to his business advisers.

"Satisfaction," he repeats, as in the darkness thousands of naked lights flare up like hearts.

"Now."

Then Jagger is off and running again.

The Dartford Delta

Mick Jagger was not born on July 26, 1944. The date was almost universally accepted until his

twenty-fifth birthday. Throughout the Sixties Jagger's publicist Les Perrin, a man in the

Hollywood tradition of George Evans (with whom he once briefly shared a client, Frank Sinatra),

insisted over and over, with the precision of an engine: "Name - Jagger, M.; born - Dartford,

Kent; on - 267- 44." It became accepted, proverbial. As late as his marriage in May 1971 Jagger's

age was widely misquoted. He did nothing to correct it. Perrin was a persuasive man. "Twentysix," he told reporters in his plausible voice, flashing his Me? Lie? baby-blue eyes. Even Jagger

was thought to believe him.

When, seven or eight centuries ago, a village youth was considered deficient in cunning or nerve,

he was liable to earn the name Scutt. The word was originally used of the tail of the hare,

particularly noticeable when the animal was fleeing. Later the Scutts became prominent in

Micklesfield, Suffolk; a William Skutt (so spelt) appears in the Subsidy Rolls there in 1545. The

family was granted a coat of arms: gold with three deer, and on a red stripe a tower between two

silver shields. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Scutts were encouraged to migrate

to Ireland, where they developed a skill for peat farming, mining and petty larceny. They were

state-sponsored settlers who undertook to keep the faith (hence "Undertakers") in return for lands

previously occupied by native Catholics. Ireland being what it was, Scutts were later among

those on board the White Sails to the New World. William and Mary Scutt settled in Virginia in

1741; William Scutts in 1754; Jacob Scutts and his wife Eva in Philadelphia in 1795. Eventually

the family was drawn as far south as Washington. After America, Australia. Not for nothing had

Scuttses crossed the globe for seven centuries. Before World War I a branch of the family had

emigrated from Greenhithe, Kent, to New South Wales, where they laboured and traded.

Possessed in the female line of musical talent, Scuttses (as they became) were prominent in

the local cathedral choir. They mined, farmed and they played cricket. The daughter of a

neighbour of Alfred Charles Scutts remembers them as "forever scheming, and planning to

move". Physically slight, their faces with closely set eyes, abundant lips, the Scuttses, she says,

"were always in a different dimension". Her chief memory is that they seemed distant.

Alfred Scutts was a yacht-builder of excessive energy. Wrinkled under the chin, around

the pale eyes that gazed longingly in the opposite direction, Alfred spoke frequently of going

home. In the event, it was his wife Gertrude who returned without him; for her,

migrating was only fulfilling the family tradition. Gertrude's neighbour remembers the statement

"we're leaving" as preceding departure by less than a month. Mother and five children set sail in

January 1917. Alfred was in search of his fortune, but meanwhile his wife and offspring travelled

steerage. Their ship, the SS Rotorua, arrived in Liverpool eight weeks later; it was snowing.

("Look," said one of the children. "White sand.") Immediately it set out on the return journey the

vessel was torpedoed and sank.

The town where they settled was in a state of barely perceptible growth. The month the

Scuttses arrived an incorporation inquiry concluded that "this ... is not a dormitory town for the

Metropolis. The building of houses has been for a population which in the main makes its living

locally . . . The Daily Telegraph Paper Mills have duplicated and construction is approaching

completion of more works ..." The inquiry put the town's population at 24,000 (including a

number of Belgian and French evacuees having fled to Britain on the outbreak of war); the

location as "an important industrial area, comprising engineering, paper-making, chemicals,

flour mills and other large works ... employing many thousands"; communications as "good",

transport "excellent", the weather (with some understatement) as "moderate". The name of this

idyll was Dartford, Kent.

Gertrude and her children settled briefly at 20 Orchard Street in the town centre. Her only

daughter, Eva Ensley, born April 6, 1913, did what any four-year-old would do. She attended the

Church of England school. She learned to cook. She queued with her mother for food. (Local

shops were frequently besieged in 1918, with meat rationing officially introduced in the southern

half of England that February.) As soon as she was able Eva was sent to work in an office in

Bexleyheath, where she remembers seeing a first flickering prototype television, and later still

became a hairdresser. By then the family lived at 233 Lowfield Street, an avenue descending due

south from Dartford Market. At weekends Eva attended dances at the nearby Glentworth Club or

the no-less-adjacent parish hall. She rode the omnibus. She sang in Holy Trinity Church. A

small, immaculately turned out teenager, personable and bright, Eva's looks were distinctive. Her

hair, which she arranged herself, was cut diagonally over her high forehead. Smiling, each

ofEva's features changed expression. Her heavy lips, the subject of much local comment, fell

open; they looked pulled-on and swollen. To compensate she developed a severe look not

unlike the actress Norma Shearer. Consequently friends found her odd. "She always thought we

teased her for being foreign," says one. Wrongly: it was the lips.

Eva was not, herself, sensitive to being "foreign". She may have deflected questions

about her upbringing, with its implied stigma of crudeness and colonialism; certainly she

developed a marked English accent. Arthur Key, who lived in the same street, remembers her as

"shy and aiming to please". Her own view is that "I fitted in pretty quickly. I had to." She seems

never to have had a sense of being deracine or even "different", neither English nor Australian.

She was, after all, bright, attractive, travelled and house-proud. The Scuttses' home was, like Eva

herself, impeccable. It was a redbrick house of modest character and despite the relative

roughness of the neighbourhood - a nearby house being burnt in mysterious circumstances - the

Scuttses' was neat, tidy and replete with the chintz, the tea-sets and knick-knacks then demanded

of Dartford society. "Inside," says Key, "it was almost a museum."

Credit for this lies exclusively with Eva. She dominated the house, she put up with her

brothers, she organised family singsongs at which Gertrude ("Gran") joined lustily in. Eva's

treatment of her family was, says Key, "saintly", though she could be irascible (as, too, have

been many saints). At a time when women married young, it was early 1940, approaching her

twenty-seventh birthday, before Eva pushed open the black iron gate, entered the red door of

Lowfield Street and announced to her mother, ''I'm engaged."

Her fiance was an almost morbidly shy man named Basil Jagger. The Jaggers were West Riding

traders whose name (variations include Jaggard, Gager, Gigge and Gigger) denotes a carrier,

pedlar or hawker. (In later years Mick Jagger preferred the etymology "knifer", derived from the

verb "jag" - to pierce or cut in tatters.) The family were no less migrant than the Scuttses. As

early as 1290 a branch setded in Glasgow, where Rudolf, Andreas and Finlay . Jagger were

traders in metal. They too were encouraged to take passage to Ireland; they too were among

those en route to the New World. Jeremy Jagger settled in Pennsylvania in 1637; his cousin

Jonathon in Connecticut a decade later. Eventually the family fanned west, where they were

granted lands along the St Lawrence and in the Niagara Peninsula. A William Jagger was

arrested for battery in Potsdam, New York, in 1861. Other members joined the Union armies in

the American Civil War. The family crest was, aptly, a hand brandishing a sword.

In England the Jaggers remained settled in Yorkshire and, by the late nineteenth century,

Kent. Only the offer of a teaching position brought David Ernest Jagger to Wickham Bishops, a

village immediately east of Chelmsford in Essex. It was there that his second son Basil Fanshawe

(his wife Harriet's maiden name) was born on April 13, 1913. For the remainder ofthe war,

during which he served in the Royal Flying Corps, David's sons were raised by two uncles. Later

he was appointed headmaster of a school at Lower Peever, Cheshire, then of St Mary's,

Greenfield, Lancashire; Basil himself was enrolled there. Early on the boy showed unusual

physical prowess. He excelled at all sports, particularly gymnastics, and was able to throw a

cricket ball further than most adults. He was also, according to a schoolfriend, "always the most

unassuming in class". Later Basil made it known that he preferred to be called henceforth by the

more genial "Joe". Joe it was.

David and his family spent much of the next decade in Greenfield. As a headmaster he

was both patient and progressive, with something gloomy about his outlook. Some of the

austerity of Lancashire rubbed off on him. Joe, in turn, was a quiet, reticent youth whose chief

distinction lay on the games field. His name is on a plaque in his Oldham grammar school as an

outstanding footballer. The same schoolfriend describes him thus: "Thin, wiry, almost rubberlike

in the legs. In gymJoe was always being held up to us as an example." He ends by adding, "It

rather embarrassed him."

Later, faced with the bleak prospect of finding a job, Joe looked south, east - even west; a

neighbour, Roger Hayes, remembers him "talking vaguely about America". He attended

Manchester University, then King's College, London. After teaching briefly in Bedford he

answered an advertisement for East Central School in Dartford where Joe arrived as a physical

education instructor in 1938. His written brief was ". .. to offer the opportunity to study PE in

detail ... providing insight, understanding and knowledge of man's movement, performance and

behaviour in sport and recreation." According to Ian King, an East Central graduate, "Joe was an

able communicator, whose chief asset was an obvious love of sport."

East Central was an all-boys school of300 students, later becoming the Downs School

and admitting girls. The decor was spartan, the regime austere. The school log records "Mr

Jagger and Mr Buzzey" as having "taken boys for a brisk walk ... as a Sunday treat." Conditions

deteriorated in 1939 when, in a single week, 27,215 gas masks were issued in Dartford and

80,000 sandbags were obtained to shore up local buildings. Hundreds Gagger included)

volunteered to serve as Air Raid Precautions personnel. Shelters were built at strategic points in

the town. In the early months of the war it was widely feared that Germany would attempt poison

attacks from the air. Children were issued with special "Mickey Mouse" masks with red rubber

face pieces and bright eye rims. Rooms in homes were gas-proofed with cellulose sheets or

curtains. Even the tops of post office pillar boxes were given a coating of yellowish gas detector

paint.

Rationing followed on January 8, 1940. Each adult received four ounces of bacon or ham

and four ounces of butter per week. 9Sugar was limited to two pounds a month. Restrictions on

meat came in March 1940. By June the bacon quota was down to three ounces, tea to two. At

times water was rationed to a pump in the town centre. The apparatus was ornate and the water

itself a faded cherry colour. Queues were long.

Joe Jagger lived in semi-detached lodgings at 147 Brent Lane in southeastern Dartford.

The house had its own garage, a vestibule, even a small front garden. The neighbourhood was a

width upward of Lowfield Street. In late 1939 he met Eva Scutts through a mutual friend; by

spring they were engaged. By then Eva had transformed into a confident, even glamorous young

woman. Engagement agreed with her. She paid renewed attention to her hair. In the food queues

she was seen reading improving books (Tom Sawyer, Key remembers). Her slight body was

clothed in bargain Utility dresses bought at market, every purchase involving a battle with other

bargain-hunters. Eva was dogged. She was determined. She it was who made arrangements to

marry; she who confirmed plans. ("Now," she was supposed to have told Joe, "or never.") The

couple took instruction at Holy Trinity. They were 27. The war outlook was grim: on September

5, 1940 a high explosive bomb demolished the women's wards at Dartford County Hospital,

killing a nurse and 24 patients. That autumn bombs were dropped on 69 of a possible 90 nights.

On December 5, Joe and Eva attended a rehearsal at Holy Trinity. Inside the windows were dark

and curtained; outside the day was mild, the river Darent at its second lowest winter level: mark

twain.