Running head: THE FOUNDATION OF SPECIAL EDUCATION

The Foundation of Special Education

Alexandria Clinger

Ball State University

1

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

2

The term special education is something that is fairly new in today’s world. Special

education has come so far, not only with how people with disabilities are treated but how they

are protected as well. Most importantly students with special needs have made tremendous

strides in the educational system. Special education students are protected through laws such as

IDEA, FAPE, LRE, IEP and many more. Other methods such as RTI, evaluation and eligibility

have truly opened up and protected all special education students. These types of laws have even

come as far as how to discipline a child with special needs. Society has created all of these

safeguards for students with special needs so that they may have the most normal and safe

educational experience possible.

Individuals with disabilities have not always been treated like they are in today’s society.

People with disabilities have been thought to be many different things throughout the centuries.

The treatment of people with incapacities varies immensely. Amongst the Greeks in Ancient

Greece people with disabilities were considered inferior and should be hidden away where no

one should see them (Munyi, 2012, p. 1). Around the 16th century people with disabilities were

considered to be possessed by evil spirits. Men and religious life subjected the mentally ill to

pain in order to perform exorcisms to get rid of the evil spirits inside of the mentally disabled.

Around the 19th century “supporters of social Darwinism opposed state aid to the poor and

otherwise handicapped” (Munyi, 2012, p.1). The Darwinism supporters reasoned that the

preservation of the “‘unfit’ would impede the process of natural selection and tamper the

selection of the ‘best’ or ‘fittest’ elements necessary for progeny” (Munyi, 2012, p.1). The rights

for people with disabilities have made tremendous strides positively. A huge component of

making this happen for special need individuals is law called IDEA, which stands for Individuals

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

3

with Disabilities Education Act (Hulett, 2009, p.9). IDEA helped change the special needs

community to have a louder voice, not only in society and education, but also in special

education law (Hulett, 2009, p.10).

IDEA is the “nation’s federal special education law that ensures public schools serve the

educational needs of students with disabilities. IDEA requires that schools provide special

education services to eligible students as outlined in a student’s individualized education

program (IEP)” (NCLD Public Policy Team, n.d). IDEA is one of two “federal statutes that most

effects special education law” (Hulett, 2009, p.5). Federal statutes have provided and given

billions of dollars to education agencies all over the United States. Some argue that IDEA has

been more of a burden then a help in the past. This is because “it has imposed a fiscal burden

greater than the support it provides” (Hulett, 2009, p.27). IDEA is frequently thought of as “an

unfunded mandate, since Congress has never fully funded more then approximately 17.8 percent

of the cost of its implementation” (Hulett, 2009, p.27). IDEA made a huge impact in education as

well the 10th and 14th Amendment.

The 10th Amendment states that: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the

Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the

people” (Hulett, 2009, p.4). It is the individual states responsibility to take care of education

throughout the state. Since these important issues were not handled the way they should have

been, serious changes began to take form throughout states. Many states take notice and pride

themselves on making education in their particular state the best that it can be. This is resulting

in states believing that “once a state undertakes the responsibility of educating children, the

education becomes a property right” (Hulett, 2009, p.4). Most frequently, we hear about Article

1 Section 8, or otherwise known as the General Welfare Clause as well as the 10th and 14th

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

4

Amendments. All three of these government movements made a huge impact in the education

world we know today. Hulett (2009) states that according to the General Welfare Clause “The

Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts

and provide for the common defense and general Welfare of the United States…” (p.4).

Consequently, Viogt (2010) states “that General Welfare Clause places restrictions on the

reasons for which taxes are levied and restrictions on how those taxes are designed” (p. 544).

The General Welfare Clause is in place to ensure the money is being spent appropriately

throughout the schools (Viogt, 2010, p. 544).

The 14th Amendment states; “no state shall make or enforce any law which shall abide

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the united states; nor shall deny any state deprive any

person of life, liberty or property without due process of law” (Hulett, 2009, p. 5). The 14th

Amendment gives students with disabilities appropriate and proper education concentrating on

what the particular need for the student may be. The 14th Amendment also refers to the rights of

the parents to have access to school records and for all of the parents to have a voice and be

heard (Sheppard, 2011).

IDEA is also huge on parent involvement in the child’s life, in and outside of school.

IDEA provides “specific procedural safeguards to help parents advocate for their child’s

educational well-being” (NCLD Public Policy Team, n.d). They also help in showing the parents

a way to ensure their child is on the right track in school and that they are kept up to date on

grades and school records. IDEA also ensures that if the parent disagrees with something the

school is doing with their child they know the proper steps to take in order to get the problem

resolved the fastest and most effective way possible. This law can be very difficult to

comprehend and understand at times so “IDEA offers a parent-friendly guide with checklists,

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

5

tips and tools to help parents embrace ways to make the law work for their child” (NCLD Public

Policy Team, n.d). Parents of children with disabilities normally have many questions when it

comes to their rights as parents. Therefore, IDEA has set up a program called PTI, which stands

for parent training and information center. PTI’s main purpose is to “provide parents with timely

information about special education so that they may effectively participate in meeting the

educational needs of their children” (NCLD Public Policy Team, n.d). They also tend to the

needs of low-income families across the nation (NCLD Public Policy Team, n.d).

IDEA is made up of six different pillars. The first of the pillars in procedural safeguard,

this is stating that all the rights of the children with special needs and their parents are getting the

protection that they need and deserve. Church (n.d.) states, “all information needed to make the

provision of free and appropriate public education to the student is provided to the parents of

children with disabilities and to the student when appropriate” (p.1). Some specific procedural

safeguards may include an inspection and review of the child’s educational records. The parent’s

are to be given full information of the full procedural safeguards from IDEA and also how to

state complaint procedures. Parents also can give consent or deny it if their child can be

evaluated or reevaluated. Another big part is that the parents have the right to be a part of the

discipline process that is set up to take form for their child in and during school (Church, n.d).

The second pillar of IDEA is free and appropriate public education (FAPE). This is a

“fundamental, nondebatable presumption embodied in IDEA that no child can be denied a public

education” (Hulett, 2009, p.32). This pillar is considered to have no rejections of free education

to any and all students with disabilities. This can include a disability that is very severe to a

disability that is mild. The range does not matter because it is stated that no one can be denied

free education. IDEA states, “that the educational program for eligible children cannot be just

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

6

any program of public education. Instead, that statute states, that the program must be special

education appropriate for the individual child” (Hulett, 2009, p.32). The term ‘free education’

means that special education is required and included because it is a public expense. This is in

effect for preschool up until secondary education (Hulett, 2009, p.32).

Next, the third pillar of IDEA is least restrictive environment or also known as LRE. LRE

“requires that’s children with disabilities be educated in the same place as all the other children”

(Hulett, 2009, p.33). There are different levels in having special education students in the general

education classrooms and these include, integration, mainstreaming, full inclusion, and least

restrictive environment. All of those different levels do not have the same meaning or purpose.

Regardless it is designed to help special education students to get the best type of education

possible. Taking a special needs student out of the classroom only happens after everything is

done in the teacher’s power to keep them there. For example Hulett, 2009 states:

Separate schooling or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular

educational environment occurs only if the nature or the severity of the disability is such

that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot

be achieved satisfactorily (p.33).

The fourth pillar of IDEA is appropriate evaluation this is the process in which “a child is

determined to have a disability requiring the support of special education services” (Hulett, 2009,

p.34). This evaluation process can help determine what stage the child is at and the type of

assistance they will need. There are very strict requirements that IDEA has when giving these

evaluations to students. Some of these requirements include; “protecting against

misidentification, include the use of a variety of assessment tools and strategies, and a

prohibition against the use of any single procedure as a sole criterion” (Hulett, 2009, p.34).

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

7

Therefore, testing must be appropriate in order to get accurate readings, whether those are

strengths or weaknesses from the student in need.

Next, the fifth pillar of IDEA is parent and teacher participation. This is the central and

most effective in terms of success in the pillars of IDEA. This means, “family, of course, means

the child and the child’s parents, and the professional means the teacher who apply their

expertise to the child’s education” (Hulett, 2009, p.34). This also corresponds with equal

organization in the decision-making process for the student. The parent has the right to

“participate in all meetings concerning their child’s education and give consent when a child

needs to have changes made in his placement” (Church, n.d).

The last pillar of IDEA is the individualized education program otherwise known as IEP.

This is the “cornerstone of educational planning and implementation under IDEA and is

undoubtedly the requirement of individualized programming for each student” (Hulett, 2009,

p.31). IEP is assigned and made for every child who qualifies for individual needs. There are six

different steps to the IEP which follow; first, “the required content of each child’s IEP” (Hulett,

2009, p.145); second, “how will the parents receive progress reports” (Hulett, 2009, p.145);

third, “who must, and how may be included in the IEP team” (Hulett, 2009, p.145); fourth,

“considerations in the development of the IEP, including certain special factors” (Hulett, 2009,

p.145); fifth, “the role of the regular education teacher” (Hulett, 2009, p.145); and sixth, “the

requirements for review and revision of the IEP” (Hulett, 2009, p.145).

The individualized education program cannot be stressed enough when it comes to the

importance of it. Students with disabilities have a long account of discrimination when it comes

to education being put first in their lives. It has not always been an easy road in getting the IEP

where it stands in today’s society. Unfortunately, “both special and regular educators are

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

8

frequently frustrated by the IEP process” (Hulett, 2009, p.146). This is resulting in schools

failing to process and follow the correct steps IDEA has put out for the IEP program. According

to Hulett (2009), the following criticisms concerning the process of IEP are which follows:

(1) Improper committee composition, (2) improper development procedures, (3) failure

to observe the timeliness requirement for development, (4) omission of required portions

of the IEP, (5) failure to provide included services, (6) delay in implementation, and (7)

failure to provide included services cost-free basis (p.146).

To avoid legal action regarding the IEP, IDEA suggests, “school personal follow every step in

the IEP planning program” (Hulett, 2009, p.146).

As previously identified above IEP and the process have hit many rough patches to get

where the program stands today. Many changes have been made along the way to insure the best

result for the student in need. For example, teachers and other facility are very busy in and

outside of school so reducing the unnecessary meetings that had been set up showed to be more

helpful to all persons involved in the long run. This is not to say that all meetings were cut with

regarding the IEP, the teachers, schools, and parents were just more particular when it came to

setting up meetings and the importance of them. There are many different changes and

components that have changed and still continue to change in regard to the IEP program (Hulett,

2009, p.148).

The case of Sacramento City Unified School District v. Rachel Holland was a huge

component in relating to pillar number two listed above, which is free and appropriate public

education. Rachel Holland was an 11-year-old girl with mild mental disabilities who had been in

a special education classroom from the very beginning. Rachel’s parents contacted the school

stating that they wanted Rachel to be more integrated into the general education classrooms with

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

9

her peers. The school decided to put Rachel in general electives, lunch and recess with her peers

but no general academic classes. Rachel’s parents were still not satisfied and still insist that she

be placed in all general academic classes and invoked their due process to request a hearing.

While all of this was going on Rachel’s parents placed her in a private school for the time being.

The hearing went accordingly to Rachel’s parents and the court was in support of Rachel. Rachel

was to undergo four prolonged tests to consider all factors of the situation. After the four tests

were completed it was concluded that Rachel was to be put into a general education classroom

with the rest of her peers. Rachel was to have a full-time supplemental aid and services but was

in a regular classroom setting all day (Hulett, 2009, p.115-116).

This is affecting free and appropriate education because the school was not doing

everything in their power to keep Rachel in a general education classroom. She was placed in the

special needs classroom from the beginning. Therefore, not undergoing the proper process to

have her be placed in a general education classroom (Hulett, 2009, p.116).

There were two interest groups that really were the first to have a collective movement

toward educating children with disabilities. Those two interest groups were CEC, which stands

for Council for Exceptional Children, and ARC, which stands for National Association for

Retarded Citizens. CEC was considered to be the first support group for children with mental

disabilities. This association was founded in 1922 in New York City. According to Hulett

(2009), “CEC has played an integral role in the development of the field, the design and

advocacy of special education legislation, and the passage of six successful reauthorizations of

IDEA” (p.19).

As previously stated above CEC is really known for their advocacy in special education

law as well as free and appropriate education. ARC is a tad different and really focuses on the

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

10

litigation aspect. According to Hulett (2009), “The two organizations proved to be formidable

powers, with CEC helping establish statutory and regulatory law via the legislative labyrinth and

ARC setting critical precedents through judicial branch” (p.19).

Special education laws have made huge steps in reassuring that all students are to be

protected at all costs. Article 7 is the heart of all questions regarding special education and how

things should be handled. The three tiers of RTI also touch on how to ensure that special

education students are in the correct placements.

According to Hulett (2009) “IDEA requires that the parent of the child receive a copy of

its procedural safeguard at the time of the initial referral” (p.125). Before the school can evaluate

the student the parent of the student must have given consent. The consent is having the parent

fill out a form and agrees to the evaluation process the child will experience specifically. The

school can never reevaluate the student unless they receive parental consent. This rule does not

apply only under grave situations or circumstances. As stated by Hulett (2009) “The evaluation

is meant to be comprehensive, and therefore, educators should use multiple methods. These

methods include the use of instruments, informal classroom methods and observations,

questionnaires, interviews, and analyses of the student’s work samples” (p.127). According to

Article 7 (2008) “The initial evaluation must be conducted and the CCC convened within fifty

(50) instructional days of the date written parental consent” (Conducting an initial educational

evaluation, 2008, p.60). Likewise, when “a student has participated in a process that assesses the

students response to scientific, research based interventions the timeframe is twenty (20)

instructional days” (Conducting an initial educational evaluation, p.60).

Article 7 refers to child find as public agencies that must maintain, establish, and apply

procedures that ensure location, identification, and evaluation to all students between the ages 3

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

11

and 22 no matter the seriousness of the student’s disability (Child find, 2008, p.55). All students

being evaluated for child find regardless of severity of their disabilities include:

Students attending a non-public school, have legal settlement within jurisdiction within

an agency, are homeless, are wards of the state, are highly mobile students, and are

suspected of being students with disabilities in need of special evaluation even if they are

advancing from grade to grade (Child find, 2008, p.55).

According to Gilchrist (n.d) Child find aims for students whose parents have conveyed concern

to teachers or other certified individuals. The pattern of behavior or performance demonstrates

need for services for the individual student. Child find also helps prevent the students with

special needs from advancing from grade level to grade level without being prepared or ready

(p.1).

Early intervening services or otherwise known as EIS is designed to help those students

who have not qualified for special education but need some extra help in the general education

classroom. According to Article 7 some of evaluations the student will undergo include

“scientifically based literacy instruction, instruction on the use of adaptive and instructional

software, and providing educational and behavioral evaluations, services, and supports”

(Comprehensive and coordinated early intervening services, 2008, p.55). In EIS it should not be

“construed to either limit or create a right to a free appropriate public education or delay

appropriate evaluation of a child suspected of having a disability” (Comprehensive and

coordinated early intervening services, 2008, p.55).

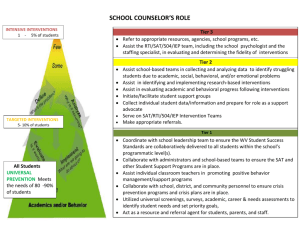

Response to intervention or otherwise known as responsiveness to intervention (RTI) is

defined according to Hulett (2009) as “a multitier process intended to identify, support, and

monitor the progress of students struggling to meet age or grade appropriate learning

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

12

expectations these students are also referred to the as the at-risk-learners” (p.133). Students who

continually fail courses and fail to meet the age level course work are most times referred to

special education services. The goal of RTI is to see more students being remediated in weak

areas in school. According to Hulett (2009) “RTI is intended to improve school wide instruction

and bolster the approaches to addressing the needs of at-risk-learners” (p.133). The RTI process

began to flourish when IDEA approved it as part of the law. As stated by Hulett (2009) “there is

no single, definitive method for implementing RTI” (p.134). RTI has three intricate tiers that

allow to system to work so efficiently. Those three tiers are universal screening, targeted

interventions, and intensive interventions and evaluation (Hulett, 2009, p.134).

The first tier to RTI is universal screening, in this tier the school and teachers identify

which students in the general education classroom are struggling the most with the assessments

that are being given to the student. These assessments include but are not limited to “universal

screeners, curriculum-based measures, state tests, district assessments, norm-referenced tests,

and teacher-made tests” (Hulett, 2009, p.134). RTI requires in tier one that the entire schools

data be collected then evaluated to act as a standard for the following semesters. According to

Hulett (2009) “the intent at this tier is to cast a broad net to identify those students at risk for

academic failure and are in need of support” (p.134). The students who qualify for RTI in tier

one should be given additional instructive services. If the student is not making any type of

progress acceptable for tier one then the student will be moved to tier two of RTI (Hulett, 2009,

p.134).

Tier two of RTI is targeted interventions; in this tier students still receive the same

general education instruction but the students are given individualized and additional instruction

as well. According to Hulett (2009) “it is critical that professionals utilize research-based

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

13

interventions during all phases of RTI” (p.134). The student’s progress should be observed very

closely during this tier particularly. The student should be assessed once a month in tier two and

if the student is not showing any progress he or she is moved to tier three.

In tier three of RTI it is known as interventions and evaluations. In this tier students are

showing weakness in very important academic areas. According to Hulett (2009) “students

receive intensive, individualized instruction using targeted interventions” (p.134). In some cases

students may have been found not eligible for special education but needed that individualized

learning style. The students at this tier are to be monitored bi weekly, if not more. The students

that are not responding to the course work in tier three may be evaluated and considered for

special education services.

The role of the special and general education teacher have changed since RTI has been

developed. According to Leonard (2012) “special educators may have various roles in each tier

of the RTI model as they plan, implement supports, evaluate, assess, collect data, and analyze

student performances” (p.13). For example, in tier 1, special education teachers may include

serving as trainers, consultants, and collaborators. Next in tier 2, special educators might include

serving as instructors, advisors, and collaborators. In tier 3 special educator roles might include

serving as trainers, consultants, collaborators, and implementers. Special education plays an

essential role in Tier 3, since many students not responding in tier 2 may be identified as eligible

for special education services. Although suggested roles and responsibilities for special

education teachers exist, they do not explain specific differences between tiers (Leonard, 2012,

p.14). According to Leonard (2012):

General education teachers will work in site-level teams to identify specific student needs

using data to make informed decisions that guide instruction for each student. Those

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

14

teams will use data in an ongoing process for strategic student intervention groupings.

Academic and/or behavioral data, collected by grade level teams, is analyzed throughout

the RTI process to measure a pattern of response to high quality interventions (p.16).

The evaluation process starts when a teacher notices a child is exuding difficulties in the

classroom and thinks that individual student needs to be evaluated academically. The teacher,

student, or the parents of the student refer the student to undergo the comprehensive initial

individual evaluation. The purpose of evaluation is to decide if a child has an educational

disability or is eligible for special education services. Also, it is to provide accurate assessment

of the student’s strengths, weaknesses, and current levels of function (Leonard, 2012, p.17).

Article 7 really puts emphasis on how everything should work in any special education

setting. Article 7 holds any answers that any teachers or employees may have regarding special

education. Some of the most frequent and most debated question is how to discipline a student

with disibilties.

When a teacher is faced with the ever so controversial topic of disciplining a special

education student, the teacher must remember that there is no difference in punishment between

a special and general education student (Hulett, 2009). Although IDEA states that special

education students are protected through procedural safeguards, that does not give the student the

exemption from being disciplined at all. If the school decides that a child with a disability is to

be expelled a certain policy must be followed. The one keen difference from a general education

student during this process is that “IDEA allows for no cessations of services” (Hulett, 2009,

p.178). That simply means that if the special education student is removed for a long period of

time or is expelled, the school must still provide educational services to that student. The

differences between disciplining a special education student versus a general education student

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

15

are very minuet. When a special education student is disciplined, it is the same punishment as a

general education student. The differences only come when “long-term removals or expulsions

for students with disabilities” are involved (Hulett, 2009, p.178).

When a student with a disability is removed from school the school does not have to

provide any type of services to that special education student for the first 10 instructional days.

This applies if the services are not given to the general education student as well. If the services

were given to the general education student within those 10 days then it would be given to the

special education student as well (Removals in general, 2008, p.106). This is also referred to as

the ten-day rule. The removal of a student during any part of the day is qualified as a removal of

the whole day. According to Article 7 “a short-term removal of a student pursuant to the students

IEP is not removal under this rule” (Removals in general, 2008, p.106). A suspension from

school is reflected as a removal but an in school suspension is not. If the special education

student using the bus transportation as part of their IEP, then a suspension from the school bus

would be considered as a removal (Removals in general, 2008, p.106). If the student is to be

removed from the school for more than 10 instructional days then the “public agency must

determine if a change of placement has occurred” (Removals in general, 2008, p.106).

The ten-day timeline is defined in Article 7 (2008) as:

Ten (10) instructional days of any decision to change the placement of a student with a

disability for violating a code of student conduct, the CCC must meet to determine

whether the student’s behavior is a manifestation of the student’s disability. (Removals in

general, p.108)

In the manifestation determinations the CCC must come to a conclusion about the student’s

behavior and one of two things must happen. If the CCC found that the student’s behavior was

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

16

because of the student’s disability the CCC must either “conduct a behavioral assessment… or if

a behavioral intervention plan has already been developed to review the plan and modify it”

(Manifestation determinations, 2008, p.108). If the removal happened after the student’s

placement then the student could return to that same placement. This is unless moving the

student’s placement is a part of the modification of the new behavioral plan.

If the student is found that his/her behavior was not a part of the student’s disability, the

school can take the following steps. The school will then proceed to discipline the student with a

disability just like a general education student. Conversely, “the student also must continue to

receive any appropriate services during any removal is ordered” (Manifestation determinations,

2008, p.108). According to Article 7 “CCC must determine appropriate services needed to enable

the student” (Manifestation determinations, 2008, p.108). These services include continued

participation in general education curriculum even though the student is not physically in the

classroom. The student’s progress toward the goals previously set by the IEP. As well as an

assessment of the student so the behavior of the student does not reoccur in the school setting.

The immediate removal of a student with a disability is determined by the following: if

the student was carrying a weapon to school or was in possession of a weapon, or if the student

inflicted serious bodily harm on someone else. Further more, if the student was intentionally in

possession of illegal drugs or was trying to intentionally sell those drugs to others the student

would be removed immediately (Interim alternative educational setting; weapons, drugs, and

serious bodily injury, 2008, p.109). The principal of the school may not keep the student accused

of the offense in an alternative educational setting for more than 45 instructional days. Still

within 10 days, the behavior must be determined to be a manifestation of the student’s disability

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

17

or not, but the placement will not change (Interim alternative educational setting; weapons,

drugs, and serious bodily injury, 2008, p.109).

The rights of the family include challenging the school for the temporary alternative

educational placement of the student with a disability. If the parents of the student with a

disability do want to follow through and challenge the school then they may request for

mediation and due process (Interim alternative educational setting; weapons, drugs, and serious

bodily injury, 2008, p.109).

Special education has come so far, not only with how people with disabilities are

treated but how they are protected under the law as well. Most importantly students with special

needs have made tremendous strides in the educational system. Special education students are

protected through laws such as IDEA, FAPE, LRE, IEP and many more. Other methods such as

RTI, evaluation and eligibility have truly opened up and protected all special education students.

These types of laws have even come as far as how to discipline a child with special needs.

Society has created all of these safeguards for students with special needs so that they may have

the most normal and safe educational experience possible. Being that support system for special

education students and their encouragement to do better each day, is what all teachers should

strive for in their careers.

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

18

References

Church, R. (n.d.). Disability rights and advocacy. Learning Disabilities Accociation of America.

Retrieved from: http://www.ldaamerica.org/aboutld/parents

Edwards, N., Gallagher, P. A., & Green, K. B. (2013). Existing and proposed child find

initiatives in one state's part C program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 32(1), 11-19.

Gilchrist, Jacky. (n.d) Early identification: How the child find program works. Special Education

Guide. Retrieved from: <http://www.specialeducationguide.com/early-intervention/earlyidentification-how-the-child-find-program-works/>.

Hulett, K.E. (2009). The legal aspects of special education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Prentice Hall.

Leonard, Julia A. (2012). Changing roles: Special education teachers in a response to

intervention model. Honors Scholar Theses. University of Connecticut. Retrieved from:

http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=

Munyi, C. W. (n.d.). Past and present perceptions towards disability: A historical perspective |

Munyi | disability studies quarterly. Disability Studies Quarterly . Retrieved from:

http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3197/3068

NCLD Public Policy Team. (n.d.). What is IDEA?. National Center for Learning Disabilities.

Retrieved from: http://www.ncld.org/disability-advocacy/learn-ld-laws/idea/what-is-idea

Sheppard, R. (2011). The 14th amendment and public education. Examiner. Retrieved from:

http://www.examiner.com/article/the-14th-amendment-and-public-education

Special Education, 511 Ind. Admin. Code 7, 2008

SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW

19

Voigt, S. T. (2010). The general welfare clause: An exploration of original intent and

constitutional limits pertaining to the rapidly expanding federal budget. Creighton Law

and Review, 43(2), 543-562.