to view my Research Paper - Allison Johnson

advertisement

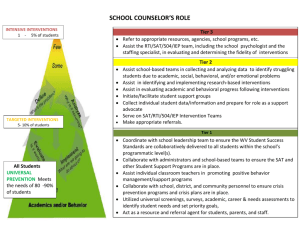

Running Heading: Law and Special Education LAW AND SPECIAL EDUCATION Allison Johnson Ball State University 1 Law and Special Education 2 Legal action is very common around the United States. It is seen in everyday life and in all corners of the country. It is important to follow the rules and laws set before the nation. These regulations are set out to keep the population safe and maintain fairness. Codes and requirements exist in special education as well. Without these rules, it would leave many people upset and feeling uneasy. A special set of legislation is set in place to protect these students, schools, and parents. In the world of special education IDEA, initially known as EHA, Education of the Handicapped Act was established in 1975 (Federal Education Budget Project, 2012). IDEA, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, guarantees families with children with disabilities education and services at a public school. IDEA has two major aspects surrounding the act: legal and social foundations. Before IDEA was in place, students with disabilities were treated very differently. Schools would often just put students into institutions with no hope that the children would become anything. It did not matter if the child had a moderate or severe disability; the student was just categorized as inferior to the rest of the students around his or her age. However, surprisingly, there is no mention of education in the Constitution. Because it does not delegate educational responsibilities to the federal government, according to the Tenth Amendment, each state is responsible for its own education systems. Also, the Fourteenth Amendment laid foundations for IDEA. The Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed the public the right to “life”, liberty”, and “property” (Hulett, 2009, p. 15). Although this was intended equal rights to all, “separate is equal” became popular. Many schools were segregated. However, in 1954 during the Brown vs. Board of Education, it Law and Special Education 3 was ruled that “separate is not equal”. Children of all races and abilities began to get equal chances. IDEA includes letting children be active participants in the classroom, support from the law, school, and parents, and not being restricted because of a disability. IDEA, sometimes called Public Law 94-142, allows students with disabilities to participate in school at their full capability. This means that under the Fourteenth Amendment, specifically the Equal Protection Clause, no child should be discriminated against (Laws.com, 2013). IDEA is essential for furthering, and not underestimating, the potential of a child with a disability. IDEA is composed of four parts and six elements. Each part of the act deals with different topics, including “General Provisions, Assistance for Education of All Children with Disabilities, Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities, and National Activities to Improve Education of Children with Disabilities” (Hulett, 2009, p. 24). Much time, effort, discussion, and legal order is put into each part of IDEA. Because times change, definitions alter, and exceptions emerge, some changes need to take place in these parts of the act. For example, in 1982 under the Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments, Part D (National Activities to Improve Education of Children with Disabilities) was enhanced refining the transition period between childhood and adulthood. In addition to these four parts are six elements or pillars. The six pillars complete IDEA. These six pillars include the “individualized education program (IEP), the guarantee for a free appropriate public education (FAPE), the requirement of education in the least restrictive educational environment (LRE), appropriate evaluation, active participation of parent and student in the educational Law and Special Education 4 mission, and procedural safeguards for all participants” (Hulett, 2009, p. 31). Without just one of these pillars, the other five would be inadequate. The six pillars of IDEA are essential. The first pillar, an individualized education program or IEP, is the main motive behind each and every child with special needs. In an IEP a child’s requirements and goals throughout his or her educational career are stated. The IEP is the basis of all of the child’s schoolwork. A child in early childhood also has something equivalent to an IEP called the IFSP or the individualized family service plan. Whether a child has an IEP or IFSP these are the child’s expectations throughout the given amount of time. The statute contains explanations of six different parts of the IEP. These parts are a written record of the child’s goals and requirements, the way the family will receive their child’s progress records, the IEP team members (special education teacher, family, student, district representative, etc.), advancements in goals and additional requirements of the child, how the “regular education teacher” will be of assistance, and qualifications of reviewing the child’s IEP (Hulett, 2009, p. 32). A child’s IEP has eight major components in its content, which add to the six parts mentioned above (Hulett, 2009, p. 153). The first component is the child’s current performance level. Both weaknesses and strengths are addressed so that the IEP team can get a clear picture of the child’s potential. Any additional support, accommodations, etc. should also be included. The second component is annual goals. The information must be presented in a way that anyone reading it can understand, no short-term or immeasurable goals can be included, goals must be related to the present level of performance, and crucial or the bottom-line goal must be included. The third component is monitoring the student’s progress, meaning providing a written record of how the student is improving or Law and Special Education 5 not improving (i.e. a report card). Any extra assistance, including accommodations, modifications, and support services is the fourth component. In this section, services that would benefit the student most, not only educational services, but also services outside of school must be included. Component five is a record of the child’s LRE. This is where the IEP team can determine where the student will function best with the least amount of help. How the child will participate in standardized tests that other students take is component six. If a student needs support services or accommodations within the test it is recorded here. Component seven includes how long and how often the services will be implemented. Lastly, within component eight the student’s transitional period services are found. When the student turns 16 years old, the IEP team meets about how the student will transition out of high school. It includes explanations of future expectations, college plans, career opportunities, and independent living. An IEP formation can be a long, tedious project. However, the benefits of a finished IEP are phenomenal. It helps the parents/guardians monitor progress and see if their child is where he or she should be. Not only does it benefit the family, but also the student themselves. With an IEP, he or she can understand goals and requirements. Lastly, the school gains knowledge of the student’s progress, as well as a better understanding of the child individually. FAPE or free appropriate public education allows no child to be denied an education because his or her disabilities. Under this law, each child with a disability must be provided with the services he or she needs to gain the most out of the educational career in the school. FAPE begins when the child is the age of three and continues until the student is twenty-one” (Hulett, 2009, p. 32). Law and Special Education 6 In the 1982 court case between the Board of Education of Hendrick Hudson Central School District and Rowley, FAPE was tested. The parents of a first grade student Amy Rowley had a hearing impairment. Her parents insisted that the school provided a full-time sign language interpreter even though Amy could read lips. Although Amy lost forty-percent of what was spoken, the school argued that the amplification systems and other services should suffice. When it reached the court systems, the courts ruled that the services provided to Amy was enough. This court case taught the public that schools are not responsible for providing the state of the art services, but only the “basic needs of the child” (Hulett, 2009, p. 32). With these expectations in mind, according to Zirkel (2013) the requirements for FAPE should be advanced in this day of age. If FAPE requirements are not heightened, “procedural violations” will happen frequently (Zirkel, 2013). It is also argued that because special education is now generally more supported financially than it was thirty years ago during this monumental court case, schools should have the opportunity to provide more advanced services. FAPE may require another thorough look in future years, but for now schools are only meant to provide the basic needs of the student. Least restrictive environment or LRE requires the child to be placed in an environment with other children where he or she can learn and be educated to the fullest potential. The IEP team must settle on a conclusion of what the LRE is for the given student. The LRE expectation is a general education classroom. However, some students will not perform to the highest potential in that environment. If this is the case, pullout periods, a resource room, or an inclusive classroom may be appropriate” (Hulett, 2009, p. 33). Law and Special Education 7 In the court case in 1983 between Roncker v. Walter, Neil Roncker, a student with moderate mental retardation, was placed in an entirely separate school for students with disabilities. His parents spoke up and argued that their son was not performing to his full potential. The court ruled and agreed with the parents, stating that Neil was not gaining the most out of his educational process because he was in a more restrictive environment than what was appropriate. This court case demonstrates that professionals should not assume that just because a student has a certain disability, he or she should be surrounded by it, but rather should be tested on his or her individual performance level” (Hulett, 2009, p. 8). The evaluation is a process “which a child is determined to have a disability requiring the support of special education and related services” (Hulett, 2009, p. 33). Under IDEA, specific rules are implemented for evaluation of a student. Many assessments must take place to gather what level the child is. These assessments have to be a variety of tests that challenge different abilities including both academic and physical. Parents and teachers should be actively involved in the student’s life and progress. The school should not discourage parent involvement, but encourage it. Some students with disabilities may do better at home than at school. Therefore with support from home, a student may begin to perform better. Regarding special education, parents may sometimes be intimidated to be active in their child’s life they could be denied benefits they think they are appropriate. However, because of the “procedural safeguards”, families should be stable and safe (Hulett, 2009, p. 34). Procedural safeguards include many factors that protect the child and the family. Families have the “right to examine all educational records, right to have an impartial hearing, right to receive certain prior notices, right to be afforded mediation, right to be Law and Special Education 8 accompanied by an attorney, and the right to have a state-level appeal” (Hulett, 2009, p. 35). Parents and schools should feel safe and protected under this law. Because of these procedural safeguards, if something needs to be disputed, it should not be forgotten about. Without this law, perhaps many groundbreaking court cases would not have occurred. IDEA is a statutory law or a “federal statute” (Hulett, 2009, p. 5). This means that a legislative group created the law. In addition to IDEA come pieces of law that apply to specific states. Article 7 is Indiana’s state regulation for special education. Article 7 includes definitions of specific language throughout the document, explanation of special education programs, formal requirements to fulfill the law set by the state, and rules for implementing special education in schools. Article 7 is based off of the federal law IDEA (The Arc, 2013). IDEA is implemented nationally, whereas Article 7 correlates specifically with Indiana law. Article 7 includes information that relates directly to schools in Indiana, where IDEA is only the basis of this article. The social and legal foundations and changes throughout history have greatly impacted the children and education system of today. Students with disabilities were formally overlooked and underestimated in the school systems. Due to the hard work of professional educators, parents, students, and legal professionals, these children can now perform without being held back. It was a long time coming for children with disabilities and educational performance, but it was all worth it. These kids have so much hidden potential and all they need is a great teacher and support to let it shine through. As Jane Sulanke (2013), Department Chair of Special Education of Muncie Southside High School, states, “all humans have gifts and disabilities. Look for the gifts.” Law and Special Education 9 Not only does the hard work of ground layers create a positive environment for special education leaners, but also the stages leading up to special education instruction. Special education includes many important elements. Steps may be taken before special education is implemented for a child. Response to intervention (RTI), evaluation, and eligibility are all used to determine if a child is in need of special education services. Article 7, Indiana’s special education law, discusses how to seek out children with special needs. Child Find is the law that states it is the school’s responsibility to seek out children in the area with special needs and adhere to the procedures set in place. Any child in need of these services, including children who “live in the area of a public agency, live in an institution, are homeless, wards of the state, are migrant students, and are suspected of having disabilities even if moving from grade to grade” (Child Find, 2008). Schools must also consider students whose parents have concern or display a pattern of repetitive behavior that shows a desire for special education services. Early intervening services (EIS) is also a big part of determining if children are in need of special education. Although EIS can help students that may be behind or struggling in school, it is not required before an evaluation if the evaluation is requested. However EIS, according to Article 7, allows the public agency to “implement scientifically-based literacy instruction” (Comprehensive and Coordinated Early Intervening Services, 2008). This means that the school needs to set a procedure to provide extra attention for students who are in need of this or will benefit from it. The “scientifically-based literacy instruction” refers to the response to intervention (RTI) that schools can set in place to give struggling students extra help before considering them for special education. RTI can be implemented all the way from pre-school to high Law and Special Education 10 school. RTI at different levels have unique negatives and positives. The main purpose of RTI is to “limit or prevent academic failure for students who are having difficulty learning” and lower the amount of children in special education (LDA, 2006). This process is not required before special education evaluation, but can be extremely beneficial. Parents do not need to give their consent before RTI is implemented; however, the school must inform the parents of the help that their child is receiving. At any time during the RTI process, parents may request to have their child evaluated for special education services. Both general education and special education teachers have their specific role in RTI. The general education teacher should be able to determine if the student needs additional help in a certain area or subject. The teacher must evaluate the student’s work compared to his or her peers. Also, the general education teacher should work alongside the special education teacher to monitor the student’s progress. The special education teacher provides the extra instruction a child may need to “catch up” to his or her peers. Similar to the general education teacher, the special education teacher should work with the classroom teacher to give feedback of how the student is improving or not. (Hulett, 2009, p. 133) RTI has three tiers that allow the school to identify students and their need for additional instruction. Tier I of RTI includes 80% of students who successfully respond to the “academic instruction and teaching strategies given to all students” (Mellard, McKnight, Jordan, 2010). Tier I includes instruction from the general education teacher and should include the core curriculum. The tier also includes three built-in assessments that should determine if the student is on a benchmark level. Tier I of RTI should communicate to the general education teacher which students respond well to the core Law and Special Education 11 curriculum without need of supplemental instruction. If the student does not respond well to Tier I, he or she should move onto Tier II (Hulett, 2009, p. 134). Tier II “includes specialized group instruction for students at risk, which is about 15% of all students” (Mellard, McKnight, Jordan, 2010). The students must participate in general education class time as well as small groups. This may be one-on-one instruction or three-to-one instruction, etc. Additional educators may be implemented to help with the student’s progress, such as a tutor or special education teacher. The student should be assessed at least once a month rather than three times a school year. Students who respond well to Tier II may move back down to Tier I. If Tier II is not helping, the student then continues to Tier III (Hulett, 2009, p. 134). Tier III of RTI is the last and final step of the process. It is for the “few students (about 5%) who demonstrate inadequate responsiveness to Tier II interventions” (Mellard, McKnight, Jordan, 2010). This is the most individualized instruction of the pyramid. Again, students in this tier are instructed in a small group atmosphere. Students are assessed more frequently than any other tier. Instructors in Tier III can be a special education teacher, tutor, reading specialist, etc. Tier III students, if responding well, can move back down to Tier II. However, if the student does not respond well he or she is typically recommended for evaluation of special education services (Hulett, 2009, p. 134). Students who do not respond well to Tier III, or students suggested for special education at any time, may move on to the evaluation process. During this process, a student is evaluated to determine the need of special education services. The purpose of evaluation is to “see if the child is a ‘child with a disability’, as defined by IDEA, gather Law and Special Education 12 information that will help determine the child’s educational needs, guide decision making about appropriate educational programming for the child” (NICHCY, 2010). The evaluation process is a very detailed and complex procedure. There are several requirements, in general, for the evaluation process. According to Article 7 (7-40-3), the test must be given in the student’s native language, appropriate for the child’s grade level and given by a professional. Students can be assessed on “development, cognition, academic achievement, functional performance, communication skills, motor and sensory abilities, available educationally relevant medical health information, and/or social and developmental history” (Educational Evaluations, in General, 2008). However, a school or parent may provide written consent to administer evaluation. If a parent makes a request to a school, the teacher, principal, school psychologist, etc. have 10 days to provide written notice. However, if the school refuses, the parents have a right to due process. Parents do not have to agree to the evaluation. Parents have the right to understand everything involved in the evaluation process either by a copy of the evaluation or a meeting explaining the results (Initial Education Evaluation; Public Agency, Written Notice, and Parent Consent, 2008). During the actual evaluation certain steps must be taken according to the law. A team of trained professionals must evaluate the student. Assessments, present levels, and classroom observations all go into a proper evaluation. The purpose of these reports is to “determine if the student is eligible for special education, and if so, what are special education services needed”. If the student has not gone through RTI, the timeline for evaluation is 50 days. However, if RTI was implemented, the student has 20 days to be evaluated. If the team determines that the student is in need of special education services, Law and Special Education 13 the team has five days to give the family a copy of the results before the CCC (case conference committee) meeting, if requested (Conducting an Initial Educational Evaluation, 2008). Identifying a student with a disability is the main purpose of evaluation. The CCC base the results off of 1) if the student is eligible for special education and 2) if so, what services need to be implemented. However, if the team finds that there has been minimal or inappropriate proper instruction of English, reading, or math, the student is not eligible for special education and services. Most importantly, a student may receive related services only if he or she is eligible for special education. After a student is found eligible for special education and services, an IEP must be implemented after a CCC meeting. (Article 7, 7-40-6). There are several disabilities that determine if a child is eligible for special education including, mental retardation, hearing impairments, speech/language impairments, visual impairments, serious emotional disturbance, orthopedic impairments, autism, traumatic brain injury, other health impairments, or specific learning disabilities, and who, by thereof, needs special education and related services (20 U.S.C. §1401). Students may also be evaluated outside of the school, which is called an independent educational evaluation. The parents have a right to disagree with the school’s evaluation and request an independent evaluation cost-free to them one time. If the school cannot provide this right, it may request grants or a due process hearing. However, if the school goes through a due process and the officer finds the evaluation appropriate for the Law and Special Education 14 student, the parents have to pay for the cost of the independent evaluation (Independent Educational Evaluation, 2008). Reevaluation is an additional evaluation after the initial evaluation that must take place every three years. However, if the parents and school find this unnecessary it may be skipped over. The timeline for reevaluations can be done annually, before the next CCC meeting or within 50 days if there is a suspected additional disability or change to services. Parent consent is required for reevaluation. However, similar to law 7-40-4 in Article 7, if the parents do not cooperate with the school, the parental consent can be disregarded if the school can provide documentation of multiple attempts of contacting the parent. The information needed in a reevaluation is very similar to that required in the initial evaluation. The main purpose of the reevaluation process is to determine if there needs to be a change to the IEP, an additional/change in disability, and/or continuation/stop of special education (Reevaluation, 2009). The special education determination process can be long and complex. However if all of the rules are followed accordingly and the proper timely manner, determination of special education and its services for a child can be done in the appropriate way. Every child deserves the right to have an education that will benefit him or her in the most effective way. With a dedicated and proactive support system for the child, the student can be the best learner he or she can be. Although all children are special, the world knows kids can misbehave or have bad days. In the world of special education these incidents need to be handled differently than that of a general education student. The discipline system in school systems is where some of these commonalities and variations between special education and general education Law and Special Education 15 students lie. Both types of students may be punished when rules are broken. General education students have fewer protections than special education students. When general education students misbehave and receive consequences, he or she may be removed, suspended, expelled, or receive another form of punishment. The way and procedure the school system executes this system may vary. However, the special education student, although these things may happen to him or her, have to follow a set procedure of rules and laws. There are several components of the special education discipline system. These components include removals, change of placement, manifestation determination, and immediate removals. All of these components and its rules need to be strictly followed. Article 7 (2008) defines removals as: “removal of a student for any part of a day constitutes a day of removal”. However, an in-school suspension does not fall into the removal category because “the student has the opportunity to progress appropriately in the general curriculum, receive the special education services specified in the student’s IEP and participate with nondisabled students to the extent the student would have in the student’s current placement” (Removals in general, 2008). When a student is removed, he or she may not receive services for the first ten days; however, on the eleventh day the school is required to continue the services laid out in the child’s IEP (Removals in general, 2008). (This is known as the ten-day rule.) Removals can lead to change of placement or no change of placement depending on the pattern of behavior. Pattern of behavior is defined as “the days occurred in the same school year, are a result of similar behaviors, and/or the length, total, and proximity of the suspensions are similar” (Grant Wood Area Education Agency, 2012). Law and Special Education 16 If a pattern of behavior is non-existent, the school must provide services on the eleventh day if the removal has lasted more than ten days. The student must still have the opportunity to “continue to participate in the general education curriculum, although in another setting and progress toward meeting the goals set out in the student’s IEP” (Removals of more than 10 cumulative days that do not result in a change of placement, 2008). If there is a pattern of behavior present and the student has been removed for ten days, a change of placement will take place. This means that the student can changes services, move schools, or receive additional services. The parents must be informed via written notice, procedural safeguards must be given, and the CCC must, within ten days, decide whether the student’s behavior was caused by the student’s disability, or Manifestation determination (Removals of more than 10 consecutive days or 10 cumulative days that result in a change of placement, 2008). The parents have the right to “mediation in accordance with 511|AC 7-45-2, a due process hearing in accordance with 511|AC 7-45-3 or 511|AC 7-45-10, or simultaneously, mediation and a due process hearing” (Disciplinary change of placement, 2008). Manifestation determination is a meeting between the CCC members to “determine whether the student’s behavior is a manifestation of the student’s disability”. This means that the purpose of the meeting is to figure out if the student’s disability was the reason behind the misbehavior. The CCC members ask themselves “1) Was the conduct at issue caused by or did that conduct have direct and substantial relationship to the student’s disability and 2) Was the conduct at issue the direct result of the LEA’s [local educational agency] failure to implement the IEP” (Hulett, 2009). If the IEP was not followed, the “public agency must take immediate steps to remedy those deficiencies” (Manifestation Law and Special Education 17 determination, 2008). If the behavior was determine to be a manifestation of the disability the “student’s CCC must conduct a functional behavior assessment, implement a behavioral intervention plan for the student or review the behavioral intervention plan and modify it, or return the student to the placement from which the student was removed” unless it will benefit the student in his or her new environment (Manifestation determination, 2008). However, if the CCC determines that the student’s behavior is not a manifestation of the disability then the faculty of the school “may apply relevant disciplinary procedures to the student in the same manner and for the same duration as those procedures would be applied to students without disabilities” (Manifestation determination, 2008). The CCC must determine if the child should “continue to participate in the general education curriculum, progress toward meeting the goals set out in the student’s IEP, or receive, as appropriate, a functional behavioral assessment and behavioral intervention services and modifications” (Manifestation determination, 2008). All decisions made by the CCC are final, unless a parent or other individual takes legal action against the decision. These legal actions may include mediation, due process hearing, or both (Manifestation determinations, 2008). Immediate removal happens when a student’s actions are not justified and create a dangerous environment to the school and/or other students. If the student “carries a weapon to school or possess a weapon, knowingly possesses or uses illegal drugs or sells or solicits the sale of a controlled substance, or has inflicted serious bodily injury upon another person” (Interim alternative educational setting; weapons, drugs, and serious bodily injury, 2008). The student may be removed from the school for no more than 45 school days. However, if this is the case, the student must remain in an educational setting. Law and Special Education 18 If an immediate removal happens “the public agency must notify the student’s parent and provide the parent with the notice of procedural safeguards” (Interim alternative educational setting; weapons, drugs, and serious bodily injury, 2008). The parent(s) may question the interim alternative education placement or IAES by mediation, a due process hearing, or both. After the immediate removal is in place the CCC must meet for a manifestation determination. If the members determine that the behavior was not a manifestation of the disability, “the student remains the in IAES” (Interim alternative educational setting; weapons, drugs, and serious bodily injury, 2008). The laws set forth by the Indiana government in Article 7 clearly state the regulations to be performed when dealing with disciplining a special education student. The school systems, public agencies, and parents must strictly follow all of these rules and laws. The guidelines for disciplinary actions greatly differ, as well as have some similarities, between general education and special education students. These laws are set in place attempt to protect everyone involved with the disciplinary action. The special education system includes heaps of complex rules and regulations. These requirements were thoughtfully laid out to protect students in special education. Additionally, all of these laws need to be carefully followed and carried out. Although some of these law may require hard work, determination, and careful planning it is worth it at the end of the day when the school, parent, and most importantly, the student is happy and succeeding. Law and Special Education 19 References Angeli, E., Wagner, J., Lawrick, E., Moore, K., Anderson, M., Soderlund, L., & Brizee, A. (2010, May 5). General format. Retrieved from http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/01/ The Arc Indiana. (2013). Special education. Retrieved from http://www.arcind.org/index/Help-for-Families/Special-Education.asp Federal Education Budget Project. (2012, March). Individuals with disabilities education act overview. Retrieved from http://febp.newamerica.net/background analysis/individuals-disabilities-education-act-overview Hulett, K. E. (2009). Legal aspects of special education. Upper Saddle River New Jersey: Pearson. Indiana Department of Education, Division of Exceptional Learners. (2008). Special education rules: Title 511 Article 7 Rules 32-47. Indianapolis: Author. Retrieved from http://www.doe.in.gov/achievement/individualized-learning/laws-rules-andinterpretations Iowa Area Education Agencies (2012). Grant Wood Area Education Agency. Retrieved from http://www.aea10.k12.ia.us/divlearn/specialeducation/docs/SE_Discipline _final.pdf Laws.com. (2013). 14th amendment. Retrieved from http://kids.laws.com/14th amendment LDA. (2006). Response to intervention. Retrieved from http://www.ldaamerica.org/about/position/print_rti.asp Law and Special Education 20 Mellard, D., McKnight, M., & Jordan, J. (2010). RTI tier structures and instructional intensity. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice (Wiley-Blackwell), 25(4), 217-225. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2010.00319.x. NICHCY. (2010). Evaluating children for disability. Retrieved http://nichcy.org/schoolage/evaluation#purposes Raven’s Guide to Special Education. (2011). Glossary. Retrieved from http://www.seformmatrix.com/raven/glossary.htm Special Education, 511 Ind. Admin. Code 7, 2008 Sulanke, J. (2013). (email communication, March 2012) Zirkel, P.A. (2013). Is it time for elevating the standard for FAPE under IDEA?. Exceptional Children, 79(4), 497-508. from