CHCFC508A: Foster children`s aesthetic and creative development

advertisement

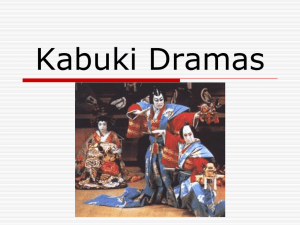

CHCFC508A: Foster children’s aesthetic and creative development Provide developmentally appropriate dramatic and imaginative play experience for children Contents Present play areas both indoors and outdoors which provide children with opportunities to enjoy dramatic and imaginative play 3 What is dramatic and imaginative play? 3 Plan/design developmentally appropriate experiences to stimulate children’s involvement 9 Overview of dramatic and imaginative play development 9 Theories of dramatic and imaginative play 12 Effects of dramatic and imaginative play on other areas of development 12 Planning developmentally appropriate play experiences 13 Provide inviting, stimulating and safe experiences for individual children and small groups of children involved in imitative, dramatic and imaginative play Superhero play 17 Drama experiences 18 Imaginative play 23 A diverse range of materials and resources to use in dramatic play experiences indoors and outdoors 25 Practical considerations for dramatic play experience 27 Provide adult support through facilitation and extension of children’s imitative, dramatic and imaginative play experiences 29 Observing and supporting children’s play 29 Role of the responsive educator 30 Present play areas which are culturally rich and reflect the diversity of families using the service Diversity of materials and gender equity References 2 17 33 33 36 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Present play areas both indoors and outdoors which provide children with opportunities to enjoy dramatic and imaginative play What is dramatic and imaginative play? What do you think dramatic play is? What is imaginative play? Can you think back to your childhood and recall your first imaginary or fantasy experience? Dramatic play essentially involves role playing—children develop the ability to engage in a role that is meaningful to their lives and the world around them. At times, children may be involved in socio-dramatic play and this involves role playing with another child or adult. Imaginative play is where children immerse themselves in fantasy, combining reallife situations and make-believe. Imaginative play may involve the use of props. Dramatic play Imaginative play Both dramatic and imaginative play are essential facets of children’s development, as they search for understanding about their reality. Piaget believes it is the most important form of symbolic thought and is critical to a child’s language and cognitive development. Statements and actions like ‘Look at me Mummy, I am a lion, roar roar’, or ‘Anne, let’s play with our dollies’ demonstrate children role playing. All of these fantasies are real in the minds of children who are engaged in this wonderful, dramatic or imaginative play. Children can switch roles—from animate Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 3 to inanimate object—with a blink of an eye. To many of us this is what childhood is all about: the ability to be anything we want without a worry in the world. Dramatic and imaginative plays are also known as pretend play, make-believe play and socio-dramatic play. Activity 1 Creating space The location of the dramatic play space is vital to the organisation and the effectiveness of the dramatic and imaginative play experience. It can determine how well children use this space, the length of time that the children are immersed in the experience, the interactions of the children and the richness of the experience. Dodge and Colker (2002) suggest educators should ask the following questions to assess the effectiveness of the play space: • • • • • • • • How often is the play space used? Which children tend to select the play space regularly? Who rarely or never wants to play in the play space, and how can I involve them in dramatic play? Are both boys and girls using the space? If only girls use the area, have I included props for boys? How is gender equity encouraged? Are children imitating TV characters or recreating their own experiences? Which props are most frequently used? Never used? Do they need to be changed? How are props used? Are children able to tidy the play space independently? When designing the space, there are specific considerations: • • • 4 Enclose the space on three sides. It should be a clearly defined area, with the props and equipment well organised. This will encourage children to return props to their original position during pack away. Depending on the design of the environment, dramatic play is ideally suited to a corner so the walls can serve as dividers. It also creates an open but enclosed feel. Avoid setting the space near quiet learning spaces such as book or creative areas. It is best near the construction, block or manipulative areas. This also encourages children to merge the two areas and promotes a sense of fun and imagination which increases the richness of the experience. Create a homelike atmosphere—displaying photos of the children and educators, providing home-like props such as cushions and pictures. Also if there is space, divide it into different sections—one section for the Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 kitchen, another area for the bedroom and then another for a ‘shop’ experience. Types of spaces Educators can create magical spaces that promote children’s imaginations and make-believe play by creating spaces or themes that promote the skills and interests of the child. Some possible topics for both indoors and outside include: Kitchen Vet clinic Hospital Shop—supermarket, clothes, shoes Bedroom—child or adult Transport vehicle Restaurant Hairdressing salon Lounge room Laundry Beautician Camping Bank Beach Post office Picnic The list is endless! Using children’s current experiences and exposure to the community will help educators choose the most appropriate play topic or theme. Home corner 1 Home corner 2 Each of these spaces requires specific amounts of furniture, equipment and props. The diversity of furniture available to purchase is endless—just check out toy shops and discount chains for many ideas. Try to keep furniture and props simple, yet authentic. Children are perfect at improvising. They do not need the latest in digital fridge technology or microwave magic. Simple, timeless items work best. Furniture that is required for a well-equipped house corner includes: • • • • • • stove and fridge child-size table and chair doll’s high chair microwave sink and cupboard kitchen dresser. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 5 Furniture for a bedroom: • • • • • • rocking chair doll bed bedroom dresser cupboard with clothes full-length mirror linen. Activity 2 Hairdressing salon 1 Hairdressing salon 2 Educators often feel that they must constantly design new and innovative ways of creating and organising the space: ‘We must do something different, we have had a Hairdressing Salon set up for a week now!’ Resist this temptation and give children the opportunity to choose the furniture, props and equipment for the space and create their own scene. Allow children to extend and challenge their dramatic and imaginative play-thinking processes. Let their play emerge gradually and naturally. Wright (1991, p 82) suggests educators should consider the following scenarios: • • • • be prepared to allow children to use an upturned table as a boat allow outdoor construction materials indoors and in the dramatic play space let children turn the home corner into a cave allow playdough to be used in conjunction with a ‘campfire’. Props for dramatic and imaginative play experiences The following table will help you to prepare and provide age-appropriate dramatic play experiences. 6 Interest area Props Shops paper bags, pens, stickers for prices, shopping bags, posters, trolleys, cash register Shoe shop shoes, variety of sizes and types, eg thongs, boots, Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 sports shoes, tap shoes, slippers, high heels; boxes, foot measure; shoe-cleaning kits, laces Supermarket selected shelves for specific items, empty packages and cartons, clothing racks, hat racks, cards and papers, frozen section using boxes for freezers, turnstiles cable reel to walk around, scanners to read prices of items. Familiar stories props related to the story, eg ‘Caps for sale’—provide children with a variety of caps Culturally diverse environments props related to specific cultures, e.g. chopsticks, Chinese crockery, different cultural musical instruments and clothes or wraps (traditional and contemporary) Post office envelopes, labels, letterbox, stamps, string, boxes, bag for delivering letters, scales, telephone book, telephone, paper, pens, street directory Doctor or dentist’s surgery syringes without needles, stethoscope, thermometer, bandages, bandaids, bowls, cottonwool, cotton buds, bottles, blankets, sheets, masks, apron, pad, paper, pencil, magazines, gowns, gloves Painter, plumber or mechanic equipment catalogues, magazines, overalls, appropriate tools and equipment, eg paint brushes, spanners, screwdrivers, taps, old engine parts, plastic pipes Dramatic and imaginative play in the outdoor environment The outdoor space is an integral component of the children’s environment. It can be often overlooked in providing dramatic and imaginative play experiences. The outdoor space is focused on provision of motor and physical experiences, which is certainly valid, yet many opportunities for enriching children’s dramatic and imaginative play can be found outdoors. When providing outdoor dramatic play experiences it is worthwhile to consider if what you are providing is an authentic experience to have outside? It often is - we spend much of our lives outside in the warmer months, eating, dining and even cooking. There are markets and shops outside as well in many towns on the weekend, not just indoors. Always consider how you might bring children’s culture and social experiences into your provisions in an authentic and meaningful way. Consider shifting part of your dramatic play space outdoors, on the veranda or under the tree. A picnic perhaps? Make a cubby house and include a selection of kitchen or dining items. Think of it like a summer house or a pergola. How else do children use outdoor spaces at home? You can also combine spaces such as the sand pit, water play, construction equipment and woodwork. You will need to consider developmental ages and Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 7 stages of the children, levels of supervision, the interests of the children and the objectives of your experience. Building outdoor space Environments that include manufactured loose parts and natural materials such as sand or soil, leaves, flowers, branches and water also encourage dramatic play. Loose parts and natural materials give children more abundant choices when it comes to materials for dramatic play. They often carry natural materials and other loose parts with them onto play structures in order to initiate or maintain dramatic play episodes. Loose parts have been found to be integral to children’s dramatic play. Activity 3 8 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Plan/design developmentally appropriate experiences to stimulate children’s involvement Overview of dramatic and imaginative play development If we are to plan appropriate dramatic and imaginative play experiences for children we need to consider their development and emerging skills. Let’s review a little here. The infant 0–12 months Development: Explores by putting everything into the mouth. Enjoys putting things onto the head. Setting and materials: Developmentally appropriate material such as containers to fill and empty. Baskets and cups to balance on the head. Role of adult: Be a role model for appropriate behaviour. Use language, name items; discuss with children what they are doing. Value of experience: Begins to enjoy cuddly toys, which later leads to imaginative play; teaches children to concentrate in their own company. The toddler Development: • • 12–18 months: Plays alone, has a short attention span. 18–24 months: Carries toys from place to place; plays with objects in a repetitive way; experiments with everything. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 9 Setting and materials: • • 12–18 months: A range of objects for exploration—pots and pans, spoons, pegs, cotton reels, plastic cups. Small containers to fill and empty. Plenty of materials, one for each child (minimum). Baskets, bags, teddies, dolls, small blankets, sheets, pillows, cradle, hats. 18–24 months: Sensory experiences—water, cellophane, wet and dry sand, paint, textured materials, leaves, bark and mud. Provide trolleys and prams. Role of adult: Show children how to fill and empty containers. Initiate play where needed—‘May I have a cup of tea, please?’ Be aware of short concentration spans and redirect and comfort children who become frustrated. Allow children to cart things around the playroom and set up their play in various spots. Value of experience: • • 12–18 months: Begins to copy adult behaviour, which is the beginning of understanding the world. Begins to give objects their correct name. Exploring leads to knowledge. 18–24 months: Repetition leads to making sense of how things function— problem solving, understanding how things work, how they feel. The two-year-old Development: Begins to use objects for purposes other than intended. Symbolic play is emerging—imitates everyday activities. Setting and materials: Hats, scarves, fabric, telephones, tea sets, blankets, empty cartons, boxes, prams, pushers, carts, wagons. Mirrors, full length at children’s level, in play room and bathroom. Plenty of space and materials on the floor. Provide more than one space set for pretend play—two or three areas for ten children. Role of adult: Plan for uninterrupted time for play to develop. Encourage role play—show a doll and say: ‘Here is the baby. Let’s take the baby for a walk.’ Place the baby in the pram. Value of experience: Allows the use of objects as other objects, for instance a doll as if it were a baby. Provides an effective medium through which children learn about the world around them. 10 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 The preschooler Development: • • • The three-year-old: Begins to play close to another child (parallel play). The four-year-old: Works jointly with others. Cooperative play is emerging. Can play out several actions in a sequence. The fiver-year-old: Can play without props. Suggests imaginative and elaborate ideas. Can be somewhat ‘rigid’ about the correct way to do something. Is often unable to foresee danger. Setting and materials: • • • The three-year -old: Dress-up clothes in separate containers: coats, trousers, dresses, capes, hats, fabrics, child-sized shoes, boxes, containers, gloves, aprons, bags, baskets. The four-year-old: Prop boxes, kitchen utensils: chair, table, furniture, mirror, storage, baskets, and telephones. Provide plenty of time for play. Provide space surrounded by shelves or plants. The five-year-old: Add a non-specific area—cubby corner, holiday corner, picnic corner as well as home corner. Plenty of time and space for children to move freely from one area to another and develop their play. Puppets, masks, children to make their own ‘stage’ for puppets—wooden box, clothes horse, TV cabinet. Props to develop children’s interest—tent for camping, picnic baskets, beds, billy, logs, straw and backpack. Role of adult: • • • The three-year-old: Ensure that you do not expect children of this age to share or take turns, prosocial skills are developing here. The four-year-old: Encourage the play with resources, props and language: ‘How can we pitch our tent?’ Play both indoors and outdoors. Actively encourage role reversal—‘Sally can be the Police Sergeant.’ Be open to many ideas and help initiate and provide for these. The fiver-year-old: Observe closely and evaluate the play. Review and bring in new materials and equipment as needed. Avoid gender-specific areas for play and consciously work towards gender equity: ‘We can all play in home corner.’ Value of imaginative and dramatic play experiences: • • The three-year-old: Helps a child solve problems about the world and understand adult roles. Develops prosocial skills, making friends, turn taking, allowing others to be the leader. The four-year-old: Encourages negotiating skills—‘What if Eleanor is the doctor, then Peter can be next?’ Teaches about real life by re-enacting experiences. Encourages sharing of materials, ideas and roles. Teaches how to handle materials with respect, putting things away in the correct Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 11 • place when finished, or leaving things for the next day to continue the play. Extends the child’s imagination. The fiver-year-old: Enriches language. Fosters gender equality. ‘Michael’s dad is a cook, he works in a restaurant’, Monica’s mum is a plumber. Remember she came to the centre to fix our leaking tap?’ Playing with water in the sandpit Theories of dramatic and imaginative play To gain an accurate understanding of how, what, when and why we plan, implement and evaluate dramatic and imaginative experiences, we need to have a sound understanding of the theories and stages of development of this type of play. To refresh your skills here read Chapter (6) Play and the Development of the Child, (pp116-127) from: Emerging: Child Development in the First Three Years, 2nd edn by Nixon and Gould. Note what Early Childhood theorists such as Piaget, Vygotsky, Garvey, Parten and Smilansky say about play and play environments. Activity 4 Effects of dramatic and imaginative play on other areas of development Listed below are influences that dramatic and imaginative play can have on other areas of the young child’s development: Physical: Small muscles, large muscles, eye-hand coordination. Social: onlooker, solitary, parallel, associative, cooperative, playmates and friendships, problem-solving and conflict-resolution skills. Language and literature: expressive language, receptive skills, written communication, literacy, grammar, pre-reading and pre-writing skills. 12 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Cognitive: physical knowledge, social knowledge, logic-mathematical reasoning, memory, imagination using props, materials, imagined props and transformed props, concept development. Emotional: identification, self-esteem, self-confidence, expressing emotions and feelings in role play. (Adapted from Nilsen, 2001) Planning developmentally appropriate play experiences Once we have established a child’s or small group of children’s dramatic play and imaginary play needs, we can design the play environment to stimulate and extend on children’s experiences and interests. Think back to your childhood—do you recall any special times when you immersed yourself in fantasy and pretend play? Did you have a magical place that you created for these wondrous experiences? Had you any favourite props that you created and used in play? Dramatic and imaginary play can be one of the most important and valuable experiences that young children enjoy and participate in within the indoor and outdoor environment. We have discussed briefly how to create a magical and exploratory dramatic and imaginary environment but we now need to look at the ‘how and what’ of dramatic play experiences. There are many factors to consider when planning developmentally appropriate and challenging experiences and these include: • • • • • • • • • • • • provision of familiar household equipment and materials opportunities for dramatic play and imitation in routines and familiar events changing dramatic play in accordance with children’s interests creating spaces that children can feeling confident in exploring different roles and using their imagination to create and challenge their knowledge and skills combining dramatic play equipment with other areas of the environment using natural, everyday materials in the experiences role of the adult within the dramatic play space assessing whether the dramatic play area is a topic of interest for the children assessing whether the children are developmentally ready for the experience providing an experience that will challenge and extend their interests, knowledge and skills engaging the children in the play opportunities for play in routines Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 13 • • provision of small individual play spaces provision of unstructured and inviting spaces. Dramatic and imaginary play experiences can evolve from everyday experiences. Mirrors and telepones—familiar household equipment Being open to spontaneous opportunities Dramatic and imaginary play experiences can evolve through ideas such as: • • • • • • hearing the sounds of fire engines talking on the phone cooking dinner watching an adult complete the ironing watching a favourite character on television bathing a sibling. All children come to the environment and program with their own ideas and understandings. It is the role of the educator to facilitate, extend and build upon the child’s competence, interests and knowledge. Carefully helping a parent wash a sibling at home can evolve into a dramatic experience at the centre of washing and dressing infant dolls 14 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Monitoring developmental readiness We know through our readings and knowledge that children’s dramatic and imaginary play follows a sequential and developmental framework. Our observations and other documented information can also give us the evidence to assess a child’s dramatic and imaginary play skills. These crucial pieces of information are essential in ensuring the educator provides appropriate but challenging experiences for the young child or a group of children within the environment. Creaser (1990) suggests that educators should also consider the following factors: • • • • • • evidence of the child’s developing imitation, then imagination development of memory skills development of social skills in group play and sharing evidence of skills to enable imaginative and complex use of materials and equipment depth of children’s past experiences information from parents about children’s dramatic play interests and abilities. Learning and developing with dramatic and imaginary play Dramatic and imaginary play is a world that provides so much fun and enjoyment for young children. As we have briefly discovered, it holds a wealth of opportunity for growth, development, acquisition of new skills and learning for the ‘whole’ child. The following table outlines specific dramatic and imaginative play experiences that can assist children’s development. Dramatic and imaginative experiences Developmental area Planning ideas Emotional development Encourage children to express emotions in their play. When reading to a child, ask how they think the character feels. Listen for the emotions that children express. Accept children’s play themes without questioning the realism. Play along with fantasy. If you are unsure how to participate, ask the child for assistance. Physical development Provide plenty of materials that children can use to create their own props. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 15 Provide writing materials. Use Velcro fasteners on clothes for young children whose fine motor skills are still developing. Provide a variety of props that will suggest different roles . Social development Help children put themselves into a character’s role such as: ‘How does a doctor help a sick baby?’ Guide children who tend to play the same roles to try new roles. Encourage discussion of roles. Encourage children to share their feelings when others upset them. Coach a child in ways to enter a group: ‘Tyson. Let’s ask the group what they are playing and if you may play too.’ Brainstorm with a child to find an ancillary role to add to a play situation occurring. When children disagree, ask questions that will help them resolve the problems. ‘Candice and Olivia, what can you do so that both of you can paly with the hat?’ Provide props that are specific to the culture of children within the centre. Focus on similarities among people. Creative Development Expose children to imaginative characters and events through picture books. Contribute to an imaginary situation as a play partner. Encourage children to describe imaginary play situations. Invite children to draw pictures or dictate stories about play themes to expand their creativity. Cognitive development Encourage children to use ‘pretend’ props when the real prop is unavailable. Pretend through songs, finger plays and music. Provide opportunities for children to use written symbols to describe their play. Guide children to solve a problem. Attach words to young children’s play to develop their language skills. Use vocabulary related to specific themes. If you are assuming a role, ask children questions to encourage them to talk about their play. (Adapted from Hereford and Schall, 1991) Activity 5 16 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Provide inviting, stimulating and safe experiences for individual children and small groups of children involved in imitative, dramatic and imaginative play Superhero play Olivia (five years) bolts into the toilet while several toddlers are washing their hands and yells at one of the toddlers: ‘I’ll get you tangled up in my web’. She then proceeds to pull the toddler away from the sink. This type of interaction can be a most enjoyable experience for a young child and quite a common scenario for educators working with young children. Essentially, young children take on the role of their favourite (or in some cases, not-sofavourite) superhero cartoon or TV character and imitate their actions, words and situations. Children’s role play can be as simple as wearing the costume during play or physically imitating specific ‘superhero’ actions. 'Superhero' costumes The development of children’s ‘superhero’ play is closely aligned with the amount of television and other technology media (including games, X-boxes, play station, Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 17 the Internet) that the child may be exposed to and the levels of adult support and facilitation. Adult response to superhero play Mayer (1993, citied in O’Brien, 2004) recommends educators, adults and practitioners need to: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • observe children’s superhero play before intruding act as facilitators, a role which includes impacting on the quality of play (ensuring it is positive as opposed to negative play) reinforce limits and boundaries: ‘We love playing Ninja Turtles, but we need to be gentle with our friends.’ change the perception of the superhero—focusing on the positive qualities (like friendships, loyalty, justice and community service) as opposed to the violence introduce real-life heroes into the child’s knowledge base discus possible alternatives to violence in solving conflicts and problems, encouraging children to make decisions about how and when they would like problems to be solved help children develop positive goals for superheros explore related concepts limit the time and place for superhero play talk about the nature of acting foster a sense of control and mastery into the play reinforce the unacceptable nature of aggression provide appropriate modelling strategies provide other experiences and activities that foster and enhance selfesteem and self-confidence. Activity 6 Drama experiences The foundations for drama experiences lie in the dramatic and imaginative play of young children. Drama is a unique and valuable method of role play but often requires thoughtful adult support and facilitation. Drama is beneficial to child development because it: • • • • • 18 develops creativity, imagination and flexible thinking requires concentration, focus and attention to detail develops the ability to communicate effectively through language encourages awareness of inner thoughts, feelings and values builds self-esteem, confidence and the ability to work with others. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Many educators avoid planning drama experiences for young children and may rely on dramatic and imaginative play as a means of fulfilling this void. Heathcote (1967 cited in Warren, 1993, p 6) defines this situation: Drama is not stories retold in action. Drama is human beings confronted by situations which change them because of what they must face in dealing with those challenges. An open-ended situation is easier for teachers who feel themselves to be novices than a story where the beginning and the end are preknown. A very useful tool for educators who are most unfamiliar and uncomfortable with the concept of drama in Early Childhood is Hooked on Drama: The theory and practice of drama in early childhood by Kathleen Warren (1993). Warren seeks to explore in detail enriching drama experiences that educators can implement within the environment and the program. Drama experiences can include: • • • pantomime—speaking without words; an example is a child raking leaves and the group guessing what the child is doing re-enacting a story—using actions, sounds and props to retell a story imaginary journey—for example, taking the children on a journey that focuses on their five senses. (Listening to the birds in the sky, the smell of the grass, the cool touch of water ..........the sweet smell of the flowers......the gentle caress of the breeze......) Planning the drama experience Warren (1993) suggests the following strategies when planning a drama experience. Do consider that some of these strategies will need to be developed over time. Choose a topic as a starting point, for example stories (Rosie’s Walk by Pat Hutchins, Possum in the House by Kirsten Jensen, Caps for Sale by Esphyr Slobodkina), folk tales, fairy tales (The Great Big Enormous Turnip, Red Riding Hood), rhymes and songs. It might even be a topic that is of interest to the children such as how trees are formed. Now: • • • • • consider the objectives or goals of the experience choose a focus for the experience—it must be challenging and exploratory to sustain the children’s interest use the children’s ideas throughout the experience use different roles during the experience promote the idea of ‘bonding’ with the character. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 19 During the experience It is best to use the children’s familiar room even if furniture has to be moved to accommodate space. • • • • • • • • • • • Remove distractions. It is a good idea to remove or turn around anything which may distract the children’s attention from the task at hand. Constant interruptions can hamper the flow of the drama. Talk about drama props. If you feel props are necessary to the drama being carried out then you will need to devise ways of encouraging children to use items with care and consideration. What about costumes? Sign and symbol are the two most important elements of the art form of drama. One of the earliest tasks in drama is for the children to be able to create and use simple signs to denote people, objects and places and to be able to respond to simple signs by appropriate activity within the drama. Think simplistically—a silver crown for a king, a cloak for a wizard, a witch or an old woman. Costumes, objects or pictures as a stimulus to drama: Although concrete objects should be used in moderation these can provide useful stimuli that will help the drama unfold, for example a necklace: ‘I wonder who would wear a necklace like that?’ Useful beginning: Begin with an adult in the role. Sometimes the adult might decide to begin the drama by being asleep. This allows the children to accept the character in their own time. The other educator can ask questions like ‘I wonder who she is and where she comes from?’ Someone will certainly suggest waking up the character and the drama experience can begin. Encourage the children to take on the many roles of the characters in the book to assist in developing their confidence and self-expression. Work in the present: A drama experience should always be set in the here and now. Using narrative: The use of narrative acts as a control device and it can be used to move the drama to a later time or event. Showing a scene: Sometimes the adults in the drama might like to show the children a short scene of what went before. For example in a drama about the kitten who lost his mittens, you could ask the children if they would like to see what happened when the kitten told their mother that her mittens were lost. How long a drama experience should be: this depends on children’s interests and focus; as well as their developmental skills. How many children can you think needed for the experience: Work with as many children as you wish. Small groups often work best. Activity 7 What to do and what to avoid 20 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 What to do What to avoid Do plan carefully. Do avoid forcing children to take part. Encourage, but never force participation. Acknowledge all contributions made by every child. Do ensure that the information within the drama is accurate. If children’s understanding and knowledge is to grow, it is inappropriate to present them with inaccurate information. Do consider the values that are incorporated into a drama experience. For example, if the children decide that a dolphin that is lost should be taken to an aquarium where it can learn tricks, should you, the educator, take the role of the lost dolphin and beg to be returned to the sea? Some children may not have thought about it themselves, thinking only that dolphins are connected with dolphin shows. Be thoughtful and sensitive in your provocations. Do be willing to stop the drama when necessary. Sometimes the educator might need to step out of role to refocus some of the children. Avoid feeling anxious if the children make seemingly irrelevant responses to questions, but treat the contribution with the respect it deserves. Avoid, as a rule, using individual children in individual roles. The child may go off on his own agenda and leave the educator struggling to maintain the plan. Avoid correcting children if they bring the wrong information to the drama. By correcting children in a drama situation you may dent their confidence so they will be less eager on the next occasion. Avoid overreacting when children suggest violent ends for some of the roles. Educators do not have to agree with their suggestions. Educators have a responsibility to encourage children to consider different responses based on thoughtful alternatives and conflict resolution. Do regard an unsuccessful drama from the adult’s perspective, as a positive experience. Even if it did not go to plan, if the children were involved and interested then it did have some successful moments. Successful drama experiences take time, practice and patience. (Warren, 1997) Dramatic play Dodge and Colker (2002) use the framework devised by Smilansky and this can be used by educators to determine the characteristics of dramatic play. It also assists in planning developmentally appropriate play experiences and characterising the type of adult interaction. Imitative role play • • • • • What role does the child play? What type of role is this? Does the child select the same role day after day? Does the child experiment with a variety of roles? How many different aspects of the role does the child play? In make-believe with props Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 21 • • • • • • • Does the child use props? Which props does the child use? How does the child use the props? Is the child interested in play with the prop, or does the prop serve as a part of make-believe? How many different props does the child use? Does the child think of symbolic and inventive uses for props? Can the child perform in the role using movements and/or words instead of objects? In make-believe actions and situations • • • • Does the child pretend with make-believe actions or situations? Does the child‘s play include fantasy? Are the elements of fantasy used by the child simple or complex in structure? Do the child’s ideas for make-believe come from stories, TV or the child’s imagination? Increase in time • • • • How much time does the child spend in a dramatic play episode? How much of the child’s time is spent in group play? Which play themes hold the child’s attention longest? How persistent is the child in carrying out the role selected? Interaction • • • • Does the child play alone? With one child? As part of a group? Who initiates group play? Is it always the same child who assigns roles and get things started? How does the child let other children know of his or her interest in group play? How does the child resolve problems in sharing props, selecting roles and giving directions? Verbal communication • • • 22 What does the child say during play? Does the child use language to communicate ideas? Give directions? Explain things? Does the child’s voice change when she or he is taking on a role? Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Children enjoy being involved in a range of dramatic play experiences Imaginative play Beaty, in Observing Development of the Young Child, p 343, Table 9, outlines the development of imagination as follows: Development of imagination Age Child’s pretend play behaviour 1–2 years Goes through pretend routines of eating or other brief actions, in some cases. 2–3 years Replays fragments of everyday experience (eg putting baby to bed) Repeats routine over and over in ritualistic manner. Uses realistic props (if at all). 3–4 years Insists often on particular props in order to play. May have imaginary playmate at home. Uses family, doll-play, hospital, cars, trains, planes and fire fighting as themes. Assigns roles or takes assigned roles. May switch roles without warning. 4–5 years Uses exciting, danger-packed themes (eg superheroes, shooting and running). Is more flexible about taking assigned roles during play. 5–6 years Plays more with doll house, block structure. Includes many more details, such as dialogue. Carries play over from one day to next sometimes. Plays more in groups of same gender. Beaty’s imagination checklist This is a practical observational method that can be used to assess children’s imaginative skills within the framework of the ‘whole child’. Several components of the checklist include: Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 23 • • • • • • • • pretends by replaying familiar roles needs particular props to do pretend play assigns roles or takes assigned roles may switch roles without warning uses language for creating and sustaining plot uses exciting, danger-packed themes takes on characteristics and actions related to the role uses elaborate and creative themes, ideas and details. Dramatic and imaginative play materials Just as we have discovered the importance of setting the right stage for dramatic and imaginary play, materials and resources are also an essential aspect. As caregivers, our role is to enrich the dramatic play of the children in our care. Dramatic play materials can be found everywhere—indoors, outdoors, in the kitchen, in the block area, in the creative area, in stories, in music and so on. The list is endless! It is the role of the educator is to ensure the materials are wellutilised, flexible, provide an abundance of rich imaginary experiences, maintain a healthy and safe aspect and are readily accessible. It is also important to provide materials and equipment that are realistic and familiar to young children. As they become older, the children can rely on their imaginations in using materials that are less realistic and more abstract. Choosing the right quantity of materials can contribute to any successful dramatic play experience. Insufficient amounts of materials can often cause frustration, boredom, be unstimulating and lead to disruption (for both educator and children) during the experience. Through careful observations and planning (and their knowledge of child development), educators will be able to select an acceptable amount of materials that will meet the needs of individual and groups of children. These strategies can reduce any incidences of boredom and frustration and encourage the children to engage in the experience for longer periods of time. Most importantly, it promotes a sign of respect for materials and equipment. Role modelling appropriate and careful use of the materials is essential to children’s play behaviour. There is nothing more unsightly to the educator and children than using old and broken pieces of equipment and materials such as a broken handle on the tea pot, dirty play shoes, ripped books—it can influence the way the children handle the equipment and it may reinforce a lack of respect and also promote the misuse of the equipment. 24 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Presentation, organisation and storage of play materials Presentation of materials is important in ensuring children enjoy the richness of the dramatic or imaginary play experience. Ensuring materials are attractively and aesthetically presented, such as dress-up clothes in a basket or hanging on coat hangers on a clothes airier, as opposed to sitting in a box on the floor. The materials should be organised in a logical and safe manner—utilising baskets, cupboards and attractive boxes. Placing labels on the storage compartments will encourage children to maintain the dramatic play area in an organised fashion. Using visual representation such as photos of the equipment on the storage compartment (just cover the photo with contact or a plastic sleeve for durability) will ensure materials and equipment are returned to their correct place. Use of wicker baskets as storage Use of shelves, baskets and boxes for storage Activity 8 A diverse range of materials and resources to use in dramatic play experiences indoors and outdoors Water Water is an excellent addition to any play area, in particular to the dramatic play space. Try a squirt bottle in the hairdressing centre, some soap and towels in the housekeeping area, cups and a teapot full of water in the restaurant and a basin and flannel in the baby centre. A squirt bottle, for example, can help children develop small muscle strength and eye-hand coordination. Empathy and an understanding of personal hygiene are enhanced when children are able to bathe their dolls. Pouring and measuring water gives children a basic understanding of maths and science. For example, comparing a dish full of water with one that is empty helps children understand the concept of weight. Pouring a Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 25 cup of tea helps children estimate quantity as they discover how much water the cup can hold. Earth Children need to play with earth. A special digging patch gives them a chance to dig holes and make mud pies and rivers without getting mud all over the garden. Children also need to work with the earth and know that it is not just ‘dirt’. They should be taught how to nurture growing things. There needs to be growing places, even if they are just tubs, pots or window boxes. Children can help prepare soil, plant seeds and tend flowers and shrubs. They can grow, harvest, prepare and eat some of their own vegetables. Sand Playing with sand is a pleasant and relaxing experience—children love the feel of sand. It is creative because children are free to do things in their own way. They can change or extend what they are doing as their imaginative, symbolic play develops. Digging, scooping, patting, smoothing and lifting are all good activities for developing muscles and coordination. Social development can be fostered as children learn to share, take turns, cooperate on projects and learn safety rules about sand play. Clay Clay is a natural, earthy material which is soft and easily manipulated by children. Children do not always need to produce objects made from clay. They may enjoy just getting the feel of the material, rolling it about their hands. Young children probably get most from the activity when they are only using their own hands. Playing with clay allows children to express ideas in a multidimensional way. Pushing, pulling, moulding and squeezing, develops children’s muscles and coordination. Children talk to others as they share the clay and share ideas, developing their social abilities and their language. Books Books can also provide children with inspiration for their dramatic play as they recreate and alter stories they have heard or read. Boxes Boxes of all sizes are another budget-wise addition to any play area. A box can become anything a child’s imagination allows it to be. Allowing children to use art materials to produce a make-believe world enhances their planning and problemsolving skills as well as their creativity. 26 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Boxes may also be used to enhance a theme-based dramatic play area. For example, a box can be used to make a cage for a stuffed animal pet store by cutting a small door on one side and a window on the other side. A box may also be fashioned into a ‘ride-em’ toy by closing the flaps, cutting out the bottom and making a hole in the top that is large enough for a child to climb through. Then attach strings (ensure appropriate levels of supervision) to make shoulder straps and use paint or other pieces of cardboard to give the box animal-like characteristics. Practical considerations for dramatic play experience Your preparation for a dramatic or imaginative play experience will involve the collecting and preparing of the appropriate props, ensuring that there will be sufficient items to meet the children’s needs. Here are some of the practical considerations. Hygiene and safety • • • All props need to be clean, sanitary and hygienically presented, e.g. combs and brushes cleaned before and during the Hairdressing Salon experience All props need to be in good repair and checked constantly; be careful of small beads, ties and scarves which may cause the children injury if inappropriately used. Dress-up clothes should be adjusted to fit comfortably and safely. (Children can easily trip in long pants, dresses, gowns.) Check clothing for sharp fastenings, buttons, brooches, which might scratch children. Stiletto shoes are very dangerous and should not be used. Shoes with closed-in toes are the safest. Location and setting • • • • • Location—if possible set up in a defined space (by using dividers—shawls, tents, cupboards, plants, etc). This will lessen distractions from other play experiences. Setting—consider the atmosphere that you wish to create for the type of dramatic play experience you are providing. The setting can be enhanced by the provision of pictures, photographs, posters, paintings, rugs, cushions, wall hangings, pot plants, mobiles, paper lanterns, hammocks, hanging bells and chimes. The arrangement of props is an intrinsic part of the setting and will assist in keeping the area attractive and orderly: clothes can be easily selected and returned if displayed on individual hooks Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 27 • • 28 picture labels can be used so that children will know where to return props and materials to cupboards, shelves, bins and containers storage—the use of ‘prop boxes’ will assist the organisation of your dramatic play aids and materials. Prop boxes will relate to specific interest areas, e.g. camping, picnic, jewellery store, monsters...... Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Provide adult support through facilitation and extension of children’s imitative, dramatic and imaginative play experiences Observing and supporting children’s play Children display an abundance of skills and knowledge during dramatic play experiences. Through careful observations you will be able to determine the level of skill the child or a group of children are displaying, and what they require to challenge and extend their abilities, interests and skills. There are many useful methods we can use to record and interpret children’s dramatic and imaginative play skills. Some of these methods you may already be familiar with through your work experience or study of other topics within this course. They include: • • • • • • • Anecdotal record—recording in past tense children’s interactions and involvement in dramatic and imaginative play experiences. Running record—recording in present tense children’s interactions and exploration of the environment. Videos or sound recordings—these can capture a wealth of information about the young child or a group of young children. (Remember, if you choose to observe and document in this manner, ensure you seek permission from the child and families.) Photography—this is a fantastic method of documenting children’s dramatic and imaginative play skills. (Remember again to seek permission from the families and the child.) Collection of creative mediums such as paintings and drawings which can present a real picture of the young child’s thoughts and ideas. Work samples—could include a drama acted by the children and costumes and other dramatic play materials that were created. Time samples—documentation of a young child or group of children over a duration in the dramatic play area. This may also help determine a play theme. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 29 • Checklists—an observational tool that gives a guide to ‘typical’ children’s developmental skills according to developmental norms. This could be use to note a child’s involvement in dramatic play experiences. Implementing a range of observational tools and methods will give us useful information on a child’s interests, development and emerging skills. This in turn will shape and inform the provisions and environments we provide. Children busy in the sandpit Activity 9 Role of the responsive educator Nilsen (2001) emphasises the importance of creating a rich and meaningful environment that fosters and enhances children’s learning abilities. In the following table Nilsen describes the educator’s role in facilitating and supporting play. Educator’s role 30 Because we know We do Children learn through their senses We provide real, three-dimensional objects for them to manipulate. Children are making associations with previous knowledge We provide materials that are familiar. Children need time to organise their thoughts We provide long periods of uninterrupted time for them to explore. Children cannot share We provide duplicates of popular materials. Children cannot wait We do not require them to all do the same thing at the same time. Children have different attention spans We provide a flexible schedule so children can move at their own pace. Children are egocentric, only seeing things from their own point of view We do not force them to internalise someone else’s point of view. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Children learn what they want to know We listen to them and provide ways for them to learn. Children learn from making mistakes We allow the mistakes to happen.. Children are frustrated easily We provide an environment and materials that are accessible and easy for them to manage themselves. Children learn from accomplishing hard tasks We let them try without rushing in with solutions. Children construct their own knowledge We provide a way for them to teach themselves. Strategies to support and facilitate children’s play There are many strategies that educators can use to support young children’s involvement and engagement in dramatic and imaginative play experiences. Essentially, educators need to: • • • • • • • • • • let the children take the lead in the play (the educator will take on the role of a play partner by getting down to the child’s level and commenting on what the child is doing.) “Sebastian, I really like the way you have set up the cups and plates for morning tea, they look very inviting. Is someone coming for tea?” provide time for satisfying play to develop (giving children blocks of uninterrupted times of play.) provide the place and, if needed, the props. pick up on children’s interests and then provide subtle ways to help them develop the play. provide shared experiences such as educators talking about their breakfast routine while the children are involved in ‘preparing breakfast.’ demonstrate negotiation skills—children might be involved in a conflict and need assistance to sort out the problem. accept children’s play for what it is rather than making it adult focused. support rather than take over the play, using lots of encouragement and praise; ensure that the educator’s interactions are meaningful. enter the play, observing when is the best time to intervene and facilitate the play; this can be imperative to the continuity and success of what is happening. “Have you thought of this, Henry?”, “That’s a great idea, Myfanway; the scarves make wonderful table cloths!” focus on the play, not the rules, allowing children flexibility in the play, for example moving the dress-up clothes to the block area. Dockett (1995) further outlines these strategies: • providing opportunities to build upon those experiences in play Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 31 • • • • • • • • • providing time, space and materials to engage in complex play providing a mixture of familiar and different materials accepting children’s play scripts and ideas wherever possible modelling appropriate negotiation and mediation strategies providing opportunities for children to negotiate and practise conflictresolution skills ensuring children’s understandings are challenged and extended observing and documenting the play in its entirety appreciating and valuing complex play encouraging complexity within the play (suggest a prop, suggest a theme, ask questions about the theme to develop and expand the play, become a play partner, observe rather than assume, model how to interact with others in pretend roles and encourage the use of language). The role that educators provide in dramatic and imaginative play is an important component of the experience. It communicates to the children that their dramatic play is valued and creates a positive experience for both educator and child. 32 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 Present play areas which are culturally rich and reflect the diversity of families using the service Diversity of materials and gender equity The richness and beauty of the world takes many forms—the craftsmanship of a basket, the feel and drape of a sari, the sounds of a lullaby. When we bring bits and pieces of the world into the daily life of our programs, the unfamiliar becomes familiar; what was outside our experience becomes part of our frame of reference.’ (Neugebauer, 1992 citied in Crook, 2004) We can create environments that embrace diverse practices and provide natural, open ended materials that reflect the many cultures, gender, races, physical and family differences and similarities of those who attend our service and are representative within our diverse communities. Materials should include: • • • • • • • • • • interest centres that reflect the different cultures of the children open ended dramatic play materials literature including books, posters, photo albums, magazines, newspapers and songs that provide children with the underpinning knowledge of other cultures and diversity puzzles, games and other cognitive materials dark and light colour for painting and other creative experiences art projects including jewellery making, sand paintings and ethnic clothing music, musical instruments and dance puppets and other dolls artefacts and other cultural objects that will assist in children’s understanding of diversity containers, baskets and other storage items that depict images that represent the diverse nature of the community. Refer to Chapter 4 of Crook (2004) Just Improvise: Innovative play experiences for children under eight, Tertiary Press, Victoria for some beautiful images of diverse, natural play materials and environments. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 33 If you are able to borrow the below two videos/DVDs from your TAFE library they will also provide a wealth of information and ideas on providing beautiful, thoughtful and sensory rich child focused play spaces. • • Macquarie University. Institute of Early Childhood Studies, 1995, Mia-Mia a new vision for day care: Infants program (under twos), Summer Hill films for the Institute of Early Childhood, Macquarie University. Macquarie University. Institute of Early Childhood Studies, 1995, Mia-Mia a new vision for day care: Program for 2-5 years olds, Summer Hill films for the Institute of Early Childhood, Macquarie University. Resources, materials and provisions that authentically present the diverse nature of our communities should be presented in play experiences on an everyday basis. This may include: • • • • • Dress-up clothes from a range of cultures; including wraps and scarves that can be used in different ways Kitchen utensils, table settings, crockery and play food from a diverse variety of cultures. For example: Chinese crockery, table ware, placements, chop sticks and different samples of play food, including sushi and rice noodles. Baskets and carrying items from different cultures, using natural materials, such as cane, hessian, tapestry cloth. Posters, prints, art works and written language examples supporting different cultures and gender roles. For example a poster could be displayed in the dramatic play area depicting both genders involved in domestic chores. Dolls, dolls clothes and associated props that a representative of a diverse range of cultures Play area set up in a Japanese restaurant Play area set up in a hospital The use of persona dolls in dramatic play There are several valuable programs and resources available to educators that assist children in developing an awareness of diversity and social justice. The most 34 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 useful and developmentally appropriate is ‘Persona Dolls’. Even though these programs do not necessarily involve role playing, the underpinning knowledge is similar. The aim of persona dolls is to: • • • • reflect the cultural, physical, socio-economic and lifestyle differences of the group so that each child can feel good about who they are present scenarios that stimulate discussion and exploration of stereotypes expose children to human diversity so that each child can feel comfortable with similarities and differences in others provide stories that encourage children to practise activist strategies so that each child can stand up for themselves and others when bias occurs. (Derman-Sparks, 1989 cited in Jones and Mules) Activity 10 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010 35 References Beaty, Janice J (2008) Observing Development of the Young Child, 7th ed, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Creaser, Barbara (1990) Pretend Play: A Natural Path to Learning, Australian Early Childhood Association, Watson ACT. Dockett, Susan (1995) You make me alive!: Developing Understanding Through Play, Australian Early Childhood Association, Watson ACT. Dodge D T, Colker L J.& Heroman, C (2002) The Creative Curriculum for Early Childhood. 4th edn, Teaching Strategies Inc, Washington DC, USA. http://www.flipkart.com/observing-development-young-childjanice/0130271535-kow3f9us3fHeathcote (1967 cited in Warren, 1993, p 6) Nilsen, Barbara (2001) Week by week: Plans for Observing and Recording Young Children 2nd ed, Delmar/Thomson Learning, Albany NY. Warren, Kathleen (1992) Hooked On Drama: The Theory and Practice of Drama In Early Childhood, Macquarie University of Early Childhood, Sydney. Wright, Susan (ed) (1991) The Arts in Early Childhood, Prentice Hall, Australia. 36 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC508A: Reader LO 9325 © NSW DET 2010