Stubbs - Palca - spanish-golden-age

advertisement

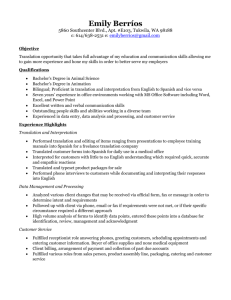

Playing With Comic Types: Teaching “An ALMOST Contemporary Drama About the Discovery of America by Spain’s Most Famous Playwright”1 Naomi J. Stubbs In my English class at LaGuardia Community College, I teach “The Drama.” This course is suggested to (and thus populated by) students in the Education, Spanish-English Translation, Writing and Literature, Theatre, and (predominantly) Liberal Arts majors. In teaching this course, I aim to provide a broad overview of dramatic literature, using texts once removed from the canon (e.g. a play by Ibsen, but not A Doll’s House, or an Argentinean adaptation of a play by Sophocles) and selecting a theme around which all the plays center (such as adaptation, revenge, or comedy). In reading Discovery of the New World, I did so with an eye to including it in the next incarnation of this syllabus: how it might intersect with themes, and how it might be introduced in class to appeal to students of the various majors. Within this working group, I am hoping to explore more fully the various ways this play could be used in a classroom from historical, textual, and performative perspectives. An idea that has come up nearly every semester, and one I would like to explore further, is the idea of stage “types.” Students often have one of two reactions to these characters when they encounter them – they laugh or they are puzzled as to how audience members/readers would have “bought” these depictions (a combination of disgust and disbelief), and often students are faced with a combination of both of these reactions – uncomfortable laughter. A reading of the Fligelman is likely to elicit this same reaction. The discussions that have emerged from such encounters (especially when looking at eighteenth-century British and nineteenth-century American plays) have led to discussions (and final papers) on the role of the stage type, investigating such issues as what role “types” play within any given play, recovering (as best as The title of this paper (not the one on the program) comes from the dust jacket of the copy I purchased. I don’t know when it was added, but it speaks to many of the reasons this play was selected. 1 one can) how such types were received by audiences, and considerations of who would have played these types and how that impacts what they represent (discussions of blackface, redface, and yellowface are closely tied). Discovery of the New World presents excellent opportunities to discuss all of these questions in relation to the scene in which Palca first appears. There are, of course, many different stage “types.” While some types either overlap or are used to stand in for many different races and ethnicities, it is the Native American type I would like to focus on here. Any such discussion would have to acknowledge the noble savage construction as well as the “dusky maiden,” and would invite a comparison of this play with Inkle and Yarico and Metamora, for example. In Native Americans as Shown on Stage: 1753 to 1916, Eugene Jones traces the stage “type” of Native Americans. Despite excluding Discovery of the New World, much similarity can be seen between the stage types and functions he identifies in British (and French) plays of the eighteenth century. Jones suggests three roles these “types” played: (1) as a lure to audiences by including Native Americans for novelty and spectacle, (2) to serve for satirical purposes (such as highlighting the faults of whites, as seen in Aphra Behn’s The Widow Ranter, 1689), and (3) as propaganda, such as depicting the English having a better relationship with the Native Americans than the French. All three of these functions can be seen in Discovery of the New World. If one were reading the play in English and did not know the author, it would be clear from the very beginning which country this was written and performed in on the basis of the depictions of the various kings. Columbus’ despair at the kings of Portugal and England not supporting what became an historical mission (a discovery being “celebrated” as I write this today--Columbus Day!). Some skepticism is presented throughout regarding Columbus’ true motives with regards to religion and gold in the trial scene and then throughout the play (most notably when Pinzon and Columbus debate when it’s too soon to ask for gold). The aspect of novelty and spectacle, however, is the role of this “type” in this particular play that I would like to focus on in this paper, in examining how it might be introduced to the classroom. Prior to addressing this specific play and specific scene, I would have a class in which we examine the use of stage types using plays we had read in previous sessions for examples. Students would have been introduced to the idea of stage types and have had in-class discussion of their forms and functions in relation to a play as written on the page. In moving to this play on a subsequent week, I would begin class by asking them how they see stage types functioning in this play (which ones do they see and what are their functions). After this initial discussion, I would divide students into small groups and have them stage our target scene. In three groups of 4 or 5, I would task these groups with staging the scene, using any found space on campus, and using the Fligelman translation. Most of these students are not theatre majors, and we would not have spent much time on staging scenes, but I would invite them to be as creative as they wish in terms of where and how to stage it. In past classes, I have found that small-group work in staging small scenes yields excellent results in terms of energy levels and engagement with the text. Often students see these as a “free” class in that they don’t think they’re doing any work, rather, they’re just having fun. As I’m sure we all know, these opportunities for “play” lead to a very different form of engagement with the text than the traditional seminar forum would typically allow for. These scenes would then be shared. Discussions of the resulting scenes could address such issues as the (un)conscious choices made with regards to how Palca speaks, what the power dynamic is, where the actors are positioned in the performance space in relation to one another, how the mirror is handled, who are we laughing at/with, and the various ways in which comedy is used. Without having the students’ scenes in front of us in advance, it’s hard to know the exact direct the conversation will go in, but presumably, given the way this translation is written, there would be many opportunities for comedy and this would likely form the heart of the discussion. We could then follow this with another class by then comparing the shared translation with one other. When Liberal Arts students study literature, they read primarily for the plot, but struggle with noting stage directions or what people are actually doing. After having performed scenes, it might be worth then looking back at the text and looking at the Stackhouse translation of just this scene to compare – not having the scenes side-by-side, but rather reading it during class and identifying what stands out to them as different (what seems different, rather than looking for specific word choices). The Stackhouse translation is not as heightened in its comedy in many ways, but also has a number of important differences. The comedy is more muted and certain details are different. For example, in the Fligelman translation, it appear the men are armed (they say “let us remove our fire-arms while she is calling the people” after Palca leaves), while in the Stackhouse translation they state they must arm themselves at the end of this scene, suggesting they were not armed throughout the encounter. Such differences as tone and details would be more apparent to the students when they consider these details in relation to their performance (and subsequent discussion), and this could then lead to a discussion of issues of translation, how comedy can mask greater divisions, and how these differences change the “type” we are presented with. Of course, much of this is vague and subject to so many variations – working with such a mix of majors, staging scenes with complete free reign in terms of choices (but limited with regards to time). Few of my classes have clear specific objectives – there is a plan and some questions I want addressed, but where the discussion goes? That’s up to the interests and reactions of the students! One of the initial responses (sorry, I don’t know who wrote which post) examines the various ways in which the mirror can be read in the context of the play, the genre, the historical period, and today – I hope we get to discuss this further!