Engage Empower Enact

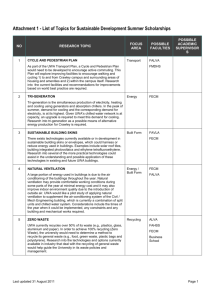

advertisement