Huang Binhong`s Late Landscape Paintings

advertisement

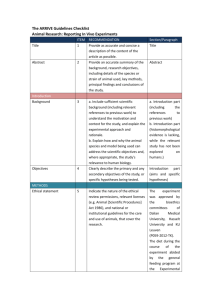

Virginia Review of Asian Studies THE UNTRAMMELED BRUSHWORK: HUANG BINHONG’S LATE LANDSCAPE PAINTINGS CHEN XIAO HONG KONG UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Introduction Probably no modern Chinese artist could exhibit more proliferated artistic creation in his life than Huang Binhong (1865-1955). Huang’s ninety-two-year life is widely regarded as an epic composed of thousands of splendorous landscape paintings. In reviewing Huang’s artistic innovation, one may find that his style of landscapes evolved highly slowly during his young and middle-aged time, suggesting a self-determined learning process with calmness and patience. Early paintings are products of Huang’s copying of diverse ancient artist models from the early Song to the late Qing dynasty, indicating his appreciation for and eagerness towards the best from the Chinese tradition. Works during his formative years bear relatively antiquarian scholarly characteristics, expressing a sense of refinement, transparency and tranquility. Not until he arrived at the final period of metamorphosis into his seemingly chaotic landscape paintings do we witness the ultimate expressive personality of the artist ‘Huang Binhong.’ Making a drastic departure from his previous works, Huang Binhong’s late stage of art perplexes viewers profoundly. Viewers find it hard to comprehend his pictures---a jumble of ink dots and apparently random brushstrokes. Huang himself, conscious of his ‘artistic incomprehensibility,’ as well claimed that his paintings could only be understood thirty years after his death. Most of his late landscapes, though intensively accomplished in a few short years, possess unprecedented unruliness realized by his ‘untrammeled brushwork.’ Such untrammeled brushwork forges his landscapes into esoteric works of abstraction, disorderliness and black massiveness. Influenced and derived from Chinese calligraphy, Huang’s untrammeled brushwork serves as the core of his eventual artistic transformation from tradition. Therefore, to investigate his untrammeled brushwork is warranted to find an answer for the eccentric beauty of his late landscapes. Huang Binhong’s Early Landscape Paintings Huang Binhong was born in 1865 in Shexian County, Anhui Province. Influenced by the traditional Confucian values and literati culture of his hometown, the little son started to obtain professional training of art and literature, with the expectation that he would step on official career after taking the civil service examination. Unfortunately, this well planned route was torn into pieces, with the abolition of the civil service exam in 1905 and the subsequent poignant social reforms brought by the Western Imperialism and domestic voices for ‘modernity’. Helplessly, Huang continued to live a homeless life by writing prolifically on art and culture as an editor, teaching art at schools and producing a numerous deal of paintings. He was forced to wander from place to place, drawn into the national transformation towards modernization passively. However, as an artistic traditionalist, the titled ‘refugee of the country’ cannot fully represent his identity. Like a sponge absorbs water as much as possible, Huang was actively participating in various artistic societies and groups in Shanghai, which aimed to build up a cultural national identity by 143 Virginia Review of Asian Studies promoting Chinese traditional art, including calligraphy, painting, epigraphy and literature. Some significant intellectual and cultural groups he was involved in were the Association for the Preservation of the National Essence and the Cathay Art Union. Besides organizing activities, he personally wrote articles of art history and theory for publications like the Journal of the National Essence, National Glories of Cathay and Collectanea of the Arts, etc. The eloquent spokesman for Chinese artistic tradition thus arrived in his late middle age, with an enormous accumulation of traditional artistic knowledge. After realizing the incompleteness of emulating masters as the only source, he made best use of intervals of work and completed plenty of grand tours to different Chinese landscapes for self-contemplation, observing nature and sketching extensively. After those tumultuous years in Shanghai, Huang was offered an appointment by the Capital District Court of Nanjing in 1935 to authenticate paintings in the Palace Museum in Beijing. Soon after his arrival there, the Sino-Japanese war broke out and the Japanese military occupied Beijing. This national adversity trapped Huang in the old capital for another ten years, but it was such abundance of time without external intervention that left more room for him to develop his artistic style. The final stage of his life eventually came when the Chinese Communist Party led by Mao defeated the Japanese invasors and the Nationalist Party around 1940s, and founded the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Sweeping out a sense of alienation from the homeland and uncertainty about his destiny, Huang Binhong settled down beside the West Lake in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. There he accepted the commission to teach Chinese painting in the China Academy of Art. The coming delightful peace of artistic life encouraged Huang to summarize his lifelong artistic theories, and allowed him to quietly practice brush-and-ink assiduously and regularly. Successfully, he achieved a unique style in landscape paintings, aided by his mature ‘untrammeled’ brushwork and accessory techniques of use of water and ink. The only incident that once impeded his creation was his impaired eyesight due to his cataract around 1953-54. Given the misfortune of blindness, his paintings of this period were tremendously black and dense, symbolizing his irreducible madness. The overall explosive transformation came to an ultimate end, when the artistic giant passed away on 25 March, 1955. Huang Binhong’s lifelong artistic creation is mainly represented in his landscape paintings. In reviewing the extant picturesque landscapes, we may clearly see his stylish evolutions shaped by the external social contexts and the internal altering artistic values and methods. His early works occupying most of his life changed at a slowly pace, while the ultimate transformation standing for merely a few years embraced a sudden explosion. To get a profound understanding on his late ‘untrammeled brushwork’, we group his landscapes before 1943 as a whole to elicit the last decade (1943-65) from eighty to Huang’s death at ninety-two. The first eighty years cover the artist’s process of learning from both ancient and contemporary artists, and his accumulated experiences of landscape after his intensive travels throughout China, whereas the following ten-year stage witnessed a metamorphosis of his landscape paintings led by his unconstrained brushwork. Early landscapes of Huang Binhong commonly demonstrate a ‘deliberate scholarly style’. The word ‘deliberate’ indicates his self-aware imitation of masters as a means of personal invention. He pointed out the significance of learning by saying that, ‘copying by one method or another is not creative work, but it is the only way to acquire the ability to create.’1 He got comprehensive inspirations from masters of the Song, Yuan, Ming, and early Qing dynasties, which was highly different from many contemporary traditionalists who were satisfied rigidly imitating the orthodox literati paintings, representative of ‘Four Wangs’ (i.e., Wang Shimin, Wang Hui, Wang Yuanqi 144 Virginia Review of Asian Studies and Wan Jian). Huang’s copying was in a systematic order as he explained, ‘I first copied Yuan dynasty painting, for its brush-and-ink is excellent. Then I copied Ming painting, for its composition is stable, and there is less chance for me to go astray. Next I copied Tang dynasty painting, for it enables me to pursue antiquity. Finally, I learned from Song painting, for its style is rich and varied. In copying, one should not be like a silk pupa that gets enmeshed a in a web of its own spinning.’2 Take Mount Jiuhua for instance, Huang’s earlier depiction ‘Mount Jiuhua’ (Fig.1) in 1906 was obviously akin to the traditional late Ming literati style. Stylistically reminiscent of Dong Qichang (1555-1636) and Gong Xian (1618-89), the picture shows inevitably stark contrast of black and white in layering of the mountains, given by a meticulous contouring brushwork at a constant velocity. It can be inferred that Huang was trying to demonstrate specific scenery by restoring detailed houses and groves of trees nearby. Another album of ‘Landscapes’ (Fig.2) in 1909 records the forty-year-old man’s deep appreciation towards the Xin’an School artists, representative of Hong Ren (1610-64), Cheng Sui (1605-91) and Zha Shibiao (1615-98) . A dry and light inked brushwork distinctly outlines the mountains, leaving merely the old pines along the precipice in dark ink, and conveys tranquility and elegance that are distant from the chaotic mundane world. Another hanging scroll ‘Landscapes in the style of Li Tang’ (Fig.3) in 1926 reveals his critical learning from masters by comparison study. He inscribed that both Tang Yin (1470-1523) and Yun Shoupin (1633-90) understood well the essence of brushwork of their mutual model Li Tang (1066-1150), but their untrammeled brushwork performed better comparatively. The picture’s one-sided composition and forceful texture of rocks remind that of Li Tang, whereas Huang’s quietly elegant landscape rendered in light ink and his highly fine brushstrokes of contouring mountains depart from the blackness of Li Tang. From Huang Binhong’s early landscapes before late 1930s, we may be tempted to conclude that these works, instilled with his admiration for the previous masters, earn a scholarly formal composition and a peaceful rhythm. The brushwork was traditional, in the process of modification led by different calligraphic scripts. Paintings due to the greyish and brownish color tones are poor in tactile sensation and personal expressive power, while remaining an elegant serenity. Huang Binhong’s long-term apprenticeship was later added in a new identity of ‘traveler’ around late 1930s. From his fifties to seventies, Huang Binhong committed himself to travelling throughout China, immersing himself discovering the ever-changing beauty of nature and its constant inner essence. He paid subsequent visits southern to Guilin, Yangshuo, Canton and Hong Kong, while setting foot western to Mount E’mei and Mount Qingcheng in Sichuan, Mount Yandang in Zhejiang and Mount Huang in Anhui. The indulgence in nature freed him to sketch extensively under shifting observations, thus beginning his stylistic experiments prepared for the later explosive transformation. The landscape paintings he finished during this period possess an intrinsic dynamic rhythm compared with his inchoate ‘scholarly’ works. A sense of freshness, movement and originality can be traced in his precipitous mountains and translucent streams. Mount Huang, one of the most inspiring places for Huang Binhong, was remodeled in his album leaves ‘Scenes of Mount Huang’ (Fig.5; 6) in 1938. Unlike many paintings from his early career, the drawings abandoned traditionally formal and constructive composition, replaced by holistic pictorial weight of the hefty mountain. Brushwork was obviously that of calligraphy that Huang had practiced assiduously. The angular strokes of dark ink outline the convex and concave contour of mountains, while the sprightly strokes of light ink successfully depict a wall of water rushing 145 Virginia Review of Asian Studies down the valley. The calligraphic brushwork vocabulary was more diverse than before to express certain effects that he yearned. Meticulous lines of small houses, crisscross strokes of grove of trees, and dots of green moss along the mountain edges make the landscapes honestly representative yet freshly alive. The rhythmic paintings tell that Huang was painting with more spontaneity and strength now, which might be explored from his growingly mature yet bold personality. An undated work in memory of his trip to Guilin was ‘Peaks of Yangshuo’ (Fig.6). The pictorial contradictions in this painting in retrospect generate a beauty of harmony. The verticality emphasized by a group of narrow and cliffy mountains in the middle is neutralized by the lower horizontally vigorous grove of trees and a house protected by it. And the contouring rendered in expressive brushwork saturated with black ink counterbalances the blank space within mountains. White representative of void, managed to depict solidity of mountains, and the greyish ink brushes of mountain planes well pacifies the extreme contrast between black and white. Both dynamic rhythm and strength are easily observed in landscapes after Huang Binhong’s cultivation from nature before early 1940s, regardless of what geographical contents he chose to tell. This demonstrates his increasingly mature calligraphic brushwork and loftier vision on nature above the formal resemblance, as he maintained that, ‘A painting with landscapes of mountains, rocks, streams and trees, if not depicted in clear brushwork, is a work from which nothing can be identified. However, the energetic expression, vigor and inner beauty of those landscapes are much in common, and vary in accordance with seasonal environment.’3 The abundant artistic tradition and calligraphy, together with nature, acted as the unremitting mechanics for his impending transformation, an era when his artistic style was ready to embrace a radical change. Huang Binhong’s Late Landscape Paintings Nobody can feel more obfuscated in Huang Binhong’s artworks than his late landscape paintings. It was never a matter of quantitative change but a dramatic explosion of novelty in Huang’s artistic life. Paintings since mid 1940s, particularly around early 1950s, including masses of his uninscribed works, share a common ‘incomprehensibility’ perceived by viewers. When first looking at his late works, one may easily concluded that they contain nothing new in the content. All one sees is mountains, streams, trees, boats in the river and houses of subtle variation. Puzzles come when figures in paintings are found disproportional and landscapes composed of jumble of ink dots are indiscernible and unpleasant. Most importantly, one cannot distinguish the exact kinds of brushstroke. At first glance, the only object one experiences is crisscross lines and overlapping ink touches, and spattered ‘dirty’ dots of all sizes. The calligraphic brushwork ran into an unprecedented unruliness and freedom, expressing anything possible the artist was eager to share. One may imagine those instant moments when Huang was applying such untrammeled brushwork in the paper, bearing the risk that few people would understand his art! Faced with similar awkwardness, Huang Binhong’s confidant, the renowned artist Fu Lei(190866) proposed formally a question in his essay ‘Viewing Paintings and Answering Questions’, ‘Huang’s paintings are predominantly landscapes, but his mountains do not look like mountains and the trees do not look like trees. The brush strokes are chaotic and do not coalesce into forms. Why is that?’ 4 With regard to such doubts, Huang admitted the inaccessibility of his late landscapes, indicating that his brand-new stylish development was in coherence with his heart and mind, and that there were reasonable explanations for his untrammeled art. He once divided ‘painting’ into three categories. The first two kinds are paintings of empty reputation, which merely resemble physical objects and paintings guilty of duping people, which display complete 146 Virginia Review of Asian Studies non-resemblance with objects and claim to express inspired ideas and feelings. Only the third category, paintings which are a seamless fusion of resemblance and non-resemblance can be regarded as ‘true paintings’.5 To pursue the ideal fusion of ‘resemblance and non-resemblance’ and the qualification of ‘true paintings’, Huang endured untold hardships and suffering, and eventually forged his untrammeled brushwork, the key to the expressive forces of his landscapes. The supreme effects of his unrestrained brushwork are primarily demonstrated in three directions. It is first seen in his transmutation towards abstraction. Undistinguishable brushwork freely applied into the paper generates semi-abstract landscapes. For the old man, it was no longer a conventional act of describing figurative pictures, but a distinctive process of unconstrained expression of his own understanding of nature. Furthermore, the lighthearted brushwork lies in painting’s ‘order within disorder’. The ostensible dirty and chaotic landscapes are in practice a well-organized fusion of brushstrokes. His reverence and curiosity of Chinese calligraphy and collections like epigraphy and seal-engraving invigorated him to develop his inimitable system of calligraphic brushwork. And it is his innovative combination of those brushwork techniques and supplemented mastery of ink and water application that realized those uncompromising ‘disorderly’ mountains. To prevent painting from suffocating blackness, Huang in addition well controlled his brushwork and compensated for an economy of luminous spaces within solid landscapes. The positive structural use of void polished his late works with an air of freshness and brightness. Huang Binhong’s insouciant brushwork first displayed its uniqueness in its extraordinary abstraction in Huang’s many works. The trial of abstract calligraphic brushwork may suggest his increasing awareness of the interchange of soul and reality, a deeper layer of communication between the artist and nature. Sometimes, abbreviated calligraphic strokes mix with each other, leaving the beginning, the middle and the end of each stroke impossible to tell, while sometimes strokes and sparse ink dots are blended together to create a fusion full of density and thickness. Huang’s abstract brushwork was derived from Chinese calligraphy, a kind of formal abstract art, where the expressive forms of writing characters convey connotation above the original objects. Without exaggerating, some of his landscapes became extremely abstract pure artworks given his experiments in line and form. Huang’s innovative abstraction was admired by the later Chinese artist who was also well-known for his formal abstraction, Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010). He once evaluated Huang Binhong’s progress towards abstraction under the traditional brush-and-ink, ‘I think Huang Binhong’s late paintings entered a stage of semi-abstraction. Comparatively, his early works rigidly adhered to the physical properties, which hindered him from expressing a beauty of rhythmic vitality, which his late landscapes managed to convey vividly.’6 The painting ‘Pine Tree Gully in Mount Huang’ (Fig.7) in 1952 well illustrates Huang’s abstract strokes blended with dots. Thoroughly transformed from the depiction of Mount Huang in the 1930s, the landscape demonstrates a fantasy of blackness. Two bulky mountains dominate the entire paper, leaving a linear blank space within the mountains as a representation of the purling Bailong Stream. Layers of dots dipped in black ink, together with short crisscross strokes and lines compose the powerful mountains. Looking from a closer distance, the nonrepresentational quality of brush movement blocks viewers from identifying any detailed objects. The non-resemblance is so aggressive, even if tinged cyanine and cinnabar applied to increase liveliness cannot help. Moreover, Huang’s predominant application of abstract lines was represented in another album leaf of ‘Landscapes’ (Fig.8). Instead of intensive layers of dots, forceful calligraphic brush lines 147 Virginia Review of Asian Studies are applied into the paper. Lines are unusually long, either spanning the river horizontally or representing the whole cliff vertically. A fisherman in the boat in the foreground, an isolated hill on the right, and straight trees standing in the upper background can only be recognized with imagination and patience of repeated viewings. The overall resemblance is achieved entirely by forms of small patches produced by intersecting lines. Interestingly, a similar effect is produced in the oil landscape ‘La Montagne Sainte-Victoire’ of Cezanne (1839-1906). Despite such difference of painting medium and techniques, the mutually abstract effect suggests that Chinese traditional art shares certain similarities with the Western art after its certain artistic evolution. An appreciation for Huang’s late landscapes by the contemporary artist Tao Ho delivers similar admiration for his abstraction of untrammeled brushwork: ‘The late period of Huang transformed nature into pure aesthetic qualities in art: the search for expressing the feeling of solidity, substance, weight, mellowness, bitterness, and the pure abstract beauty of creation. Landscape no longer represents scenery; color transcends the materialistic appearance and takes in the translucent quality of jade, while the brushstrokes of ink, full of varieties and inner strength, dance on the paper vigorously with the rhythm of life.’7 Not only achieving the abstract beauty of ‘resemblance within non-resemblance’, Huang Binhong’s untrammeled brushwork intrinsically accomplished his ‘order within disorder’. The first unkempt impression impedes viewers’ sight from entering the chaotic mountains. The freely flying brush strokes are perceived motley due to his impatience and casual execution of brush. However, when taking several steps closer to the hanging scroll, viewers may find that the apparently irrational brushwork is in fact ingenious variation of brush lines! Huang cited an analogous phenomenon that Dong Qichang (1555-1636) observed from Dong Yuan’s paintings (?-962) to explain his ‘order within disorder’, ‘Dong Qichang said of Dong Yuan’s skill in manipulating the brush: I have seen a section of a Dong’s painting which apparently consists of nothing but innumerable random marks of the brush. But when the painting was hung up and viewed from a distance, all the trees, stones and cottages surfaced, as if by magic, without any poorly executed strokes.’8 To achieve this ‘order within disorder’, Huang decisively pointed out the key was brushwork, ‘Textural brushstrokes should be properly controlled so that they are arranged in an orderly way and do not seem to clash with each other.’9 Upon his maturity of landscape paintings, he concluded the required skills into the ‘Five methods of brushwork’, epitomizing his brush techniques after years of painstaking practice.10 The ‘Five methods of brushwork’ elucidates five brush techniques fundamentally derived from Chinese calligraphy: ‘balanced’ (ping), ‘round’ (yuan), ‘sustaining’ (liu), ‘heavy’ (zhong), and ‘changing’ (bian). ‘Balanced’ (ping) is an idea from the calligraphic aesthetic ‘drawing lines with an awl in the sand’ (zhui hua sha), in which each stroke is strong enough to penetrate the paper instead of lightly touching it. ‘Round’ (yuan) is likely influenced by Huang’s absorption of the round forms of seal-script of bronze inscriptions, exhibiting an inner strength in even lines exactly like bending a woman’s hairpin (zhe chai gu). It requires the brushwork own great resilience, in particular when the brush is to change its direction. The third method ‘sustaining’ (liu) is like traces left by roof leaks on the wall (wu lou hen), where the brush moves spontaneously yet in the control of the body. ‘Heavy’ (zhong) asks for wielding the brush with unyielding vigor, like a falling stone from a high peak. Finally, ‘changing’ (bian) requires both the brushwork and the painting vary as a whole to capture the ever-changing nature.11 Theoretically, ‘balanced’, ‘round’, ‘sustaining’, and ‘heavy’ are characteristics of the bronze and stele inscriptions, indicating that Huang’s concrete calligraphic brushwork was dedicated to his industrious study of the ancient inscriptions. 12 And 148 Virginia Review of Asian Studies the last knack ‘changing’ was an overall principle to paint with greatest flexibility. Besides the five-method guidance, Huang in addition explicated his approaches, ‘in using the brush, there should be no vertical stroke without a slight movement backwards and no horizontal stroke without a slight movement backwards. The goal is to achieve solidity and to avoid superficiality’, ‘in sketching the outlines of a painting, the brushwork must have one wave (form of rise and fall) and three zigzags (brush’s directional changes); both should change in accordance with the subject’.13 The three-meter-long masterpiece ‘Crisp air in mountains and lakes’ (Fig.9) created in 1951 exemplifies Huang’s diverse and solid applications of calligraphic brushwork. A later annotation in the painting by the contemporary artist Huang Jusu (1897-1986) discloses calligraphy as the fundamental root of Huang’s untrammeled brushwork, ‘the seal script and clerical script are combined in harmony in depiction of the painting, to express a beauty of indistinction, partly hidden and partly visible.’ The seemingly hodgepodge of black brushstrokes is in fact a combined result of Huang’s ‘changing’ brushwork. The ‘balanced’ and ‘heavy’ brushwork contouring the vein of mountains is tense and vigorous, displaying the overwhelmingly verdant nature in the horizontal axis, while the ‘round’ brush tip portrays lively mottled green and black moss. Mixed with light ochre and malachite, paralleled brushstrokes made up of one wave and three zigzags depict the beautiful riverbank. Brush lines have abandoned rigid movement neither vertically or horizontally, and turned out full-bodied and rich in variety. The picture hence is filled with a rhythmic movement, flowing from one mountain to the river, and to another mountain. Equally weighted is his masterwork ‘Landscape in the style of Song’ (Fig.10) finished at the age of ninety. ‘Sustaining’ brushwork is given spontaneously yet in the absolute control of Huang. Overpowering ink lines are either solidly bent into treetops of weeping willows along the riverside, or softly waved as representation of ripples in the lucid river. All kinds of tailored ‘changing’ brushwork altogether arrest the richness and vividness of nature, luring viewers’ entry to the agreeable mountainscape layer after layer. Notably, the upper inscription best elucidates Huang Binhong’s ultimate artistic ideal: solidity and density in structure and freshness and moisture in brush-and-ink (hun hou hua zi). Separately, ‘hun’ (round) and ‘hou’ (dense) require honestly strong and thick brushwork to compose a holistically invincible mountainscape overwhelming viewers while inviting them in. ‘Hua’ (beautiful) and ‘zi’ (luxuriant) accentuate creating a prosperous and energetic nature.14 Admittedly, the innovative use of ink and water serves as an equivalent catalyst for Huang Binhong’s cluttered yet orderly landscapes, compared to his extraordinary play of brush. Both a ponderous blackness of mountains and a gauzy thinness of streams are fruits of his ink mastery, which can be regarded an accessory of his untrammeled brushwork. Huang maintained a similar view by saying, ‘The wonder of the ancient masters’ use of ink lies in the manipulation of water. The metamorphosis of water and ink, however, lies in the strength of the brush, for without forceful brushwork, ink becomes insipid.’15 In a letter to his confidant Fu Lei, he highlighted the brushwork again as foundation for the use of ink, ‘Since the ancient times there have been no one adept at applying ink without first knowing how to use brush. If one is weak in his strength of wrist, his brush cannot well control the application of ink. People who learn painting must first learn to use the brush and then apply the ink. Only through the strength given by brushwork will the painting obtain the vital breath of harmony and the inner beauty of nature.’16 Along with his ‘Five methods of brushwork’, Huang summarized his innovation of ink into the ‘Seven methods of ink’: thick ink (nong mo), light ink (dan mo), broken ink (po mo), splashed ink 149 Virginia Review of Asian Studies (po mo), left-over ink (su mo), accumulated ink (ji mo), and scorched ink (jiao mo).17 Furthermore, according to Jason Kuo’s examination, Huang developed at least nine techniques in manipulation of water: water with ink, water breaking ink, ink breaking water, water breaking colors, colors breaking water, soaked water, splashed water, congealed water, and absorbing water. 18 Huang’s renowned masterpiece ‘Sitting in the Rain in Mount Qingcheng’ (Fig.11) demonstrates his unduplicated ‘light ink’ and ‘spreading water’ techniques. The gentle brush saturated with clear water, added with a little cyanine, best captures moisture of the evergreen Mount Qingcheng after rain. Plural layers of light ink touches obscure most space surrounding the mountain, leaving the only cottage standing out with greatest clarity. The vertically dark mountain in the middle takes on a fresh look as well, as though the earlier rain has scoured out all the dust and dirt. The contrasting huge empty space of the two sides outside as a representation of the pervasive mist further underlines a sense of humidity and mildness, as if the damp in the mountain is dripping out of the picture. Huang Binhong’s highly sophisticated methods of brushwork, complemented with his use of ink and water, gifted him incessant possibilities to express contradictory effects on the blank paper, from thinness to thickness, dryness to moisture, and elegance to roughness. All these combinations of opposite effects are orderly expressed to present speciously disordered pictures. In particular, his proficient skills even permitted him to painting when his eyesight was aggregated into almost blindness around 1952. Other than infuriating him, the visual inconvenience in retrospect freed Huang to apply even more layers of black ink, leaving mountains unbelievably black and dense. Spontaneously marked dots and strokes danced in a euphonious rhythm following his heart on pictorial surface. Perhaps it is in need of stepping further than holding full satisfaction just because of Huang Binhong’s dominant blackness, regardless of its abstraction or randomness of brushwork. One may feel questioned when thinking twice on his dark landscapes. Why an unknown brightness is naturally experienced in such blackness? And why a fresh air is captured preventing suffocation from such inevitably darkness? The solution lies in Huang’s mastery of pictorial composition, which was attributed to his dedication to Chinese calligraphy without exception. His landscapes achieved the best combination of solidity and void, and this void-solid reciprocity in return makes his landscapes fresh, lucid and vivacious. The interplay of void and solidity is considered one of the most essential structural aesthetic of Chinese calligraphy, where ‘solidity’ means the inked strokes on paper, and ‘void’ refers to the blank space outside the strokes. The dynamic momentum of the writing character can only be achieved when the void and solidity balance each other in harmony, making the spirit of character stand out. 19 Huang Binhong started his void-solid conception when he was first admonished by the Anhui artist Zheng Shan (1811-97) as a kid, that it was easy to depict solidity but hard to deal with void in painting. This conception was further developed after 1901, when he began collection and study of epigraphy and seal-engravings which were also regarded subfields of calligraphy. The reserved blank outside the character of the confined stone seal, from the calligraphic perspective, kept reminding and inspiring him the similarly positive use of void against substance.20 Thanks to Huang’s interactive combination of free brushwork and creative composition, landscape paintings of his final period are impenetrably dense on one side, while exhibiting sporadic large and small blank room to guarantee a sense of illumination and freshness. He once used an apropos simile to describe his structured composition, ‘Painting a picture is like playing chess. Success 150 Virginia Review of Asian Studies depends on the ability to create ‘living eyes’ (breathing spaces), the more the better. What to chess playing are ‘living eyes’ are breathing spaces to painting’, ‘A good chess-player arranges pieces naturally and gracefully, making a feint to the east but attacking in the west, and then gradually tackling the details, thus taking the initiative in every stage of the game. This shows the player’s ability to stay ‘relaxed.’ A good painter should also be able to stay ‘relaxed.’ At first he made a loose overall arrangement, then dots and dyes ink layer upon layer to make it look profound and lovely, thus providing a lively feeling’.21 His ‘Travel on a River’ (Fig.12) in 1952 offers strong evidence in the harmonious synthesis of substance and void. Four large black spots representing the shady exuberant trees are interlaced with sporadically large and linear blank space representing the limpidly flowing streams. Greyish ink touches are considerately applied layer after layer along the riverside to moderate the abrupt conflict between the trickling rivulets and arrogant masses. Black and white eventually turn balanced to delineate a harmonious oneness of mountains and rivers, neither crammed nor empty. Furthermore, instead of merely acting as open space to balance the composition, such positive use of luminous voids brings out the infinite splendor of nature, an inevitable momentum that penetrates and pervades the whole paper through Huang’s detailed arrangement of untrammeled black brushwork. He deliberately punctuated subtle voids within mountains by inhibiting the unruly brushstrokes from full coverage. Hence the visual pleasure of pure denseness and blackness is well expressed after the mollification of voids. Similar methods of void-solid play are easily examined in most of his late works, from ethereal cloudy sky, rising enshrouding mist to crystal-clear fjords. Huang Binhong’s attainments of brushwork never ceased to flourish only till the last second of his life. During the approximately last two years, he completed a tremendous deal of works without inscription, indicating a hidden self-awareness of ‘incompleteness’. Interestingly, these unfinished landscapes are controversially regarded as Huang’s daily impromptu practices, whereas interpreted as ‘completeness’ disguised by his unruly brushwork. In March 1955, after days of health deterioration, the old man finally passed away. His magnificent incomplete works marked with untrammeled brushwork may be the last mystery he left for people to speculate. Conclusion ‘None of my landscapes resemble the works of ancient artists, but I take pains in all respects to fathom and emulate ancient artists,’ Huang Binhong’s own words concisely summarizes his ninety-year artistic life.22 He spent the first seventy years absorbing knowledge from the Chinese tradition and nature, while the last twelve years witnessed his inimitable novelty in late landscape paintings representative of his untrammeled brushwork. Given his unprecedented brushwork mastery derived from Chinese calligraphy, his final works exhibit an abstract beauty of ‘resemblance within non-resemblance’. The refined methods of brushwork and complementary innovation of ink and water in addition endowed his landscapes with blackness, density, and thickness, inducing viewers to investigate the hidden orderliness within the apparent randomness. To finally lift his landscapes, Huang experimented on the positive use of void. Luminous blank spaces thus penetrate the aggressive hefty mountains, bringing in freshness and lightness. Consequently, his untrammeled brushwork played an indispensable role to realize his artistic desideratum—solidity and density in structure and freshness and moisture in brush-and-ink. Since the twentieth century, though Chinese artists have achieved enormous artistic breakthroughs inspired by Western art, one can hardly ignore the magnificent contributions of Huang Binhong to the reforms of Chinese painting. His aesthetic principles on brushwork in the final period not only 151 Virginia Review of Asian Studies inherited Chinese cultural relics of calligraphy and literati painting, but even more substantially his free and abstract brushwork enabled later generations of artists to discover more plausible paths for Chinese painting transmutation within tradition. Upon examining Huang Binhong’s eventual explosive transformation in landscapes, let us bring back our attention to his artistic evolutions during the ninety-year labyrinth. The ingenuity of landscapes in the end merely stays for one decade for him, compared to the absolutely dominant length of previous eighty-year accumulation of emulating ancient masters. This phenomenon further inspires us to consider why Huang expended eighty years of slight artistic variation to wait for such a fleeting eruption. Is it possible that something unexpected or meaningful once happened and enlightened him to make such a lifeway decision? Or is it simply resulted from his deliberate persistence on slowly progress? These are questions in need of further investigation. NOTES 1 T.C.Lai, Huang Bin Hong (Huang Pin Hung) 1864-1965 (Hong Kong: Swindon Book Company, 1980), p. 52. Wang, Bomin, Huang Binhong hua yu lu. 3d ed (Shanghai: Ren min mei shu Publishing, 1978), p. 50. 3 Zhang Zhenwei, ‘Hun hou hua zi, Gang jian e nuo,’ in Xin mei shu. Vol4. (Hangzhou: Xin mei shu za zhi bian jib u, 1982), n.p. 4 Claire Roberts, Friendship in Art: Fou Lei and Huang Binhong (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), pp. 70-80. 5 Wang Bomin. Huang Binhong hua yu lu, p. 1. 6 Wu Guanzhong, ‘Guan yu chou xiang mei,’ in Rong, Sipin and Mei, Wenge, ed., Wu Guanzhong: Yishu Sanlun (Shanghai: Wen hui Publishing, 1998), p. 30. 7 Jason C. Kuo, Transforming Traditions in Modern Chinese Painting: Huang Pin-hung’s Late Work (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2004), p. 177. Originally in Tao Ho, ‘The Late Period of Huang Binhong,’ in An Exhibition of Works by Huang Binhong, n.p 8 Huang Binhong, ‘Shatin Questions and Answers,’ in T.C.Lai, Huang Bin hong (Huang Pin Hung) 1864-1965, p. 25. 9 Ibid., p. 25. 10 Huang Binhong, Hua fa yao zhi (1934), in Chen Fan, Hua fa yao zhi (Hong Kong: Wan zhu tang, 1961), pp. 4-13; Huang Binhong, Hua tan, in Chen Fan, Huang Binhong hua yu lu (Hong Kong: Shanghai shu ju publishing, 1976), pp. 1-9. 11 Trans. Richard M. Barnhart, Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America, vol.18, reproduction in Jason C. Kuo, Innovation within Tradition: the Painting of Huang Pin-hung (Williamstown: Hanart Gallery in association with Williams College Museum of Art, 1989), pp. 34-5. 12 Su Biyi, ‘Huang Pin-hung’s pursuit of brush and ink,’ in Jinxian Li ed., Bi mo lun bian (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Faculty of Art and Hong Kong Chinese University Joint Publishing, 2002), n.p. 13 Wang, Bomin, Huang Binhong hua yu lu, p. 34; 41. 14 T.C.Lai, Huang Bin Hong (Huang Pin Huang) 1864-1965, p. 42. 15 Susan Bush and Hsioyen Shih, Early Chinese Texts on Painting (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), p. 34. 16 Wang Jiwen, Bin hong shu jian (Shanghai: Shanghai Peoples’ Fine Arts Publishing House, 1988), p. 40. 17 Huang Binhong, Hua tan, in Chen Fan, Huang Bin hong hua yu lu (Hong Kong: Shanghai Shuju Publishing, 1976), pp. 1-9. 18 Jason C. Kuo, Transforming Traditions in Modern Chinese Painting: Huang Pin-hung’s Late Work, p. 97. 19 Daniel Lau, Void-Solid Reciprocity: Ink-Rubbing Calligraphy. Retrieved Aug.1, 2013, from http://noonhappyhour.com/Void-Solid-Reciprocity-Visual-Branding-Book-Design 2 152 Virginia Review of Asian Studies 20 Jason C. Kuo, Innovation within Tradition: the Paintings of Huang Pin-hung, p. 25; Catherine, Woo, Chinese Aesthetic s and Qi Baishi (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 1986), p. 96. 21 Wang Bomin, Huang Binhong hua yu lu, p. 5; trans. In T.C.Lai, Huang Bin Hong (Huang Pin Huang) 1864-1965, p. 50; Chang Feng, Tan yi lu, trans. Jianping Gao, The Expressive Act in Chinese Art: From Calligraphy to Painting (Uppsala: Uppsala University, 1996), pp. 65-6. 22 Huang Binhong, Letter to Duanshi (1940), trans. In Jason C.Kuo, Transforming Traditions in Modern Chinese Painting: Huang Pin-hung’s Late Work (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2004), p. 167. 153 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Illustrations 1. Mount Jiuhua (ca.1906), hanging scroll, ink on paper. 66.5×31 cm. (Williams College Museum of Art, Gift of Tao Ho, Class of 1960) 2. Landscapes (1909), album leaf, ink and color on paper. 36×36 cm. (Hong Kong Museum of Art) 3. Landscape in the style of Li Tang (1926), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 79.4×31.7 cm. (Hong Kong Museum of Art) 4. Scenes of Mount Huang (1938), album leaf, ink and color on paper. 31.9×19.6 cm. (Hong Kong Museum of Art) 5. Scenes of Mount Huang (1938), album leaf, ink and color on paper. 31.9×19.6 cm. (Hong Kong Museum of Art) 6. Peaks of Yangshuo (undated, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 103×41.5 cm. (Private collection) 7. Pine Tree Gully in Mount Huang (1952), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 90×28.5 cm. (National Art Museum of China) 8. Landscape, album leaf (undated), ink and color on paper. 25×18 cm. (Courtesy of the Fu Family Trust) 9. Crisp air in mountains and lakes (1951), handscroll, ink and color on paper. 30.6×300 cm. (Private collection) 10. Landscape in the style of Song (undated), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 81.5×30.5 cm (Zhejiang Provincial Museum) 11. Sitting in the Rain in Mount Qingcheng (undated), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 86.5×44.4 cm. (Zhejiang Provincial Museum) 12. Travel on a River (1948), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 118×39 cm. (Courtesy of China Gallery) 154 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.1. Mount Jiuhua (ca.1906), hanging scroll, ink on paper. 66.5×31 cm. (Williams College Museum of Art, Gift of Tao Ho, Class of 1960) 155 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.2. Landscapes (1909), album leaf, ink and color on paper. 36×36 cm. (Hong Kong Museum of Art) 156 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.3. Landscape in the style of Li Tang (1926), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 79.4×31.7 cm. (Hong Kong Museum of Art) 157 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.4. Scenes of Mount Huang (1938), album leaf, ink and color on paper. 31.9×19.6 cm. (Hong Kong Museum of Art) 158 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.5. Scenes of Mount Huang (1938), album leaf, ink and color on paper. 31.9×19.6 cm. (Hong Kong Museum of Art) 159 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.6. Peaks of Yangshuo (undated, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 103×41.5 cm. (Private collection) 160 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.7. Pine Tree Gully in Mount Huang (1952), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 90×28.5 cm. (National Art Museum of China) 161 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.8. Landscape, album leaf (undated), ink and color on paper. 25×18 cm. (Courtesy of the Fu Family Trust) 162 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.9. Crisp air in mountains and lakes (1951), handscroll, ink and color on paper. 30.6×300 cm. (Private collection) 163 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.10. Landscape in the style of Song (undated), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 81.5×30.5 cm (Zhejiang Provincial Museum) 164 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.11. Sitting in the Rain in Mount Qingcheng (undated), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 86.5×44.4 cm. (Zhejiang Provincial Museum) 165 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Fig.12. Travel on a River (1948), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 118×39 cm. (Courtesy of China Gallery) 166 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Select Bibliography Andrews, Julia F. and Kuiyi Shen. A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1998. Brown, Claudia and Chou, Ju-hsi. Transcending Turmoil: Painting at the Close of China’s Empire 1796-1911. Phoenix: Art Museum, 1992. Bush, Susan. The Literati on Painting: Su Shi to Tung Ch’i-Ch’ang. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971. Bush, Susan and Hsio-yen Shih, ed. Early Chinese Texts on Painting. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. Cahill, James, ed. Shadows of Mount Huang: Chinese Painting and Printing of the Anhui School. Berkeley: University Art Museum, 1981. Cheng, Francois. Empty and Full: The Language of Chinese Painting. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1994. Chiang, Yee. Chinese Calligraphy: An Introduction to Its Aesthetic and Technique. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1973. Edwards, Richard. Introduction: The Search for Cosmic Truth. Hong Kong: Hanart Gallery with Williams College Museum of Art, 1989. Fong, Wen C and others. Between Two Cultures: Late-Nineteenth and Twentieth-Century Paintings from the Robert H. Ellsworth Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2001. Gao, Jianping. The Expressive Act in Chinese Art: From Calligraphy to Painting. Stockholm: Gotab, 1996. Hong Kong Museum of Art, ed. Homage to Tradition: Huang Bin Hong 1865-1955. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Museum of Art, 1995. Huang Pin-hung hua-lun. Zhengzhou: Henan renmin chubanshe, 1997. Huang Pin-hung shan-shui hsieh-sheng hua-kao. Hong Kong: Poyachai, 1981. Huang Pin-hung shu-hsin-chi. Shanghai: Shanghai gushi chubanshe, 1999. Kuo, Jason C. Heirs to a Great Tradition: Modern Chinese Paintings from the Tsien-hsiangchai Collection. College Park, Md: Department of Art History and Archeology, University of Maryland at College Park, 1993. Kuo, Jason.C. Innovation within Tradition: the Painting of Huang Pin-hung. With an introduction by Richard Edwards and a contribution by Tao Ho. Williamstown, MA: Williams College Museum of Art, 1989. Kuo, Jason.C. Transforming Traditions in Modern Chinese Painting: Huang Pinhung’s Late Work. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2004. Kuo, Jason C. Visual Culture in Shanghai 1850s-1930s.Washington: New Academia Publishing, 2007 Lai, T.C. Huang Bin Hong (Huang Pin Hung) 1864-1955. Hong Kong: Swindon Book Company, 1980 Li, Jinxian, ed. Bi Mo Lun Bian. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Faculty of Art and Hong Kong Chinese University Joint Publisher, 2002. Maxwell, K. Hearn and Judith, G. Smith, ed. Chinese Art Modern Expressions. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001. Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, ed. Studies on 20th Century Shan shui hua. Shanghai: Shanghai Shuhua Publishing, 2006. 167 Virginia Review of Asian Studies Roberts, Claire. Friendship in Art: Fou Lei and Huang Pin-hung. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010. Ross, David. ‘Huang Binhong’s Unruly Pastoral.’ Southeast Review of Asian Studies, vol.32 (2010) Sullivan, Michael. Chinese Art in the Twentieth Century. California: University of California Press, 1959. Tu, Weiming. ‘Iconoclasm, Holistic Vision, and Patient Watchfulness: A Personal Reflection on the Modern Chinese Intellectual Quest’, Daedalus, vol.116, no. 2 (Spring, 1987) Wang, Bomin. Huang Bin Hong. Shanghai, 1979. Wang, Jiwen. Bin hong shu jian. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 1988. Wang, Y.Jing and Li, J. Feng. Gudian yu xiandai, Huang Binhong Lun. Hefei: Art Publisher of Anhui, 1998. Wang, Zhongxiu, ed. Huang Binhong nian pu. Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 2005. Wong, Wucius. The Tao of Chinese Landscape Painting: Principles & Methods. New York: Design Press, 1991. Yang, Xiaoneng, Hong, Zaixin and Gao, Tianmin. Tracing the past, drawing the future: master ink painters in twentieth-century China. Milan: 5 Continents Editions, 2010. Zhao, Zhijun. Huang Bin-hong lun hua Lu. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Art Publishing House, 1993. 168