DRUM THERAPY SINGAPORE©

Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

DRUM THERAPY SINGAPORE©

Calming beats, rhythmic connections

Module Book 1

written and developed by Yuro T.

(www.singaporedrumtherapy.com)

Welcome to Drum Therapy Singapore©.

Many articles have been written about drum therapy and how it helps the

participants in physical, social and emotional aspects.

And these claims have been backed by scientific studies and researches

mostly done in the west. We at Drum Therapy Singapore believe that these

benefits should now come to our region and be part in making quality of life

better. Asia is a center of economic growth. With progress comes added

stress for the working individual and lesser time for the parent to bond with

the growing children.

We want to help.

Drum Therapy Singapore© is committed to bringing the value of therapeutic

drumming and drum circles initially to Singapore and the rest of Asia.

Plans to set up the first clinical study to prove its effectiveness to Asian are

already in place. And we are confident that in a few years, you will be part of

history as you become one of the first to benefit from drum therapy.

Led by a qualified and experienced music instructor who is passionate about

music and children, Drum Therapy Singapore has regular drum circles with

participants ranging from 3 to 79 years old.

Everyone reaps the benefits of Drum Therapy. The preceding article is a

compilation of what have been said and written regarding drum therapy. It our

hope that you will get to understand and appreciate it better after reading

through. But the best way is to take part in one of our drum circles and feel

the tensions released, the emotions cleared and general well-being enhanced.

History:

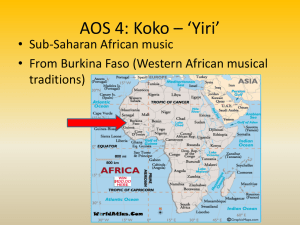

From ancient time, group drumming is being used as a tool for wellness and

community building.

Music is effective because it is a nonverbal form of communication, it is a

natural reinforcer, it is immediate in time and provides motivation for

practicing nonmusical skills. Most importantly, it is a successful medium

because almost everyone responds positively to at least some kind of music.

Drum circles are a cultural phenomenon that have been featured in Time

Magazine, Discovery and even Natural Beauty and Health. Drum circles are

probably one of the most ancient forms of community building known to man.

Here, people come together to create an improvised composition that

becomes the score for their own lives. The drum circle is a platform for

musical expression and it is accessible to anyone regardless of age or ability

level. The use of the drum presents for creative expression.

Drum circles are happening in many places. People attend these events not to

become better percussionists, but to reduce stress, build community, and

have fun. It is a recreational activity that engages the mind, body, and spirit.

In drum therapy, it’s not about performance, it’s about feeling good about

one’s self.

In one article, drum therapy was described as fun, relaxing and entrancing,

and made for a great feeling of community. In a series of sessions that were

part of a study to see if drum therapy helps heart patients, the results

observed by Miranda Ritterman from UC Berkeley were encouraging.1

There are many uses and benefits of Drum Therapy, among which are for:

The elderly and the sick

This method have been proven in many part of the world and have benefitted

numerous elderly. It mimics a community and participants instantly feel a

sense of belonging. 2

Drumming is a complex composite intervention with the potential to modulate

specific neuroendocrine and euroimmune parameters in a direction opposite

to that expected with the classic stress response.5

In a study among Oncology Patients by Christine Stevens, James Gordon, MD

of the Mind-Body Center in Washington D.C. was quoted as saying

"Oncologists should be open to group drumming if their patients are

interested in it. Drumming can put people in a state of relaxation. It was used

as a healing technique 1,000 years ago. Why not now?" (MAMM Magazine,

July/August, 2001) 6

Even the Canadian Cancer Society espouses Drumming as good for cancer

patients. And the healing power of drumming for Alzheimer patients was

explored in a book by drum facilitator Robert Lawrence Friedman. 8

Adults

Drumming technique for assertiveness and anger management in the shortterm psychiatric setting for adult and adolescent survivors of trauma. 9

In the April 2010 issue of Science of Mind Magazine entitled "Good

Vibrations" with David DiLullo and Rick Allen (Def Leppard, Raven Drum) by

Barbara Stahura where they expressed that drumming “increases heart rate

and blood flow. It also synchronizes the hemispheres of the brain, causing

brain waves on both sides to entrain, of fall into the same pattern, which can

produce effects similar to deep meditation. Entrainment also occurs among

members of the drumming group, bringing about a sense of oneness and

community.” 10

These same experts also mentioned that drumming helps your brain and your

health. 11

Women also have special interest and emerging expertise in this area. Their

important role and perspective is highlighted in an interview published in

Drum! Magazines March2010 issue. 12

Children with special needs

There are many Scientific Researches that support that Music Helps Children

Mentally. Drumming is a vital part of music and enables the benefits of Music

therapy to be reaped in Drum therapy as well.

Students

There are a lot of article supporting and proving that drumming help the

young deal with their substance abuse issues. 13

Drugs have been a menace to society and interestingly, it is the adolescents

who are easily hooked on drugs that are also particularly interested in

drumming. 14

Drumming has also been used as complementary Therapy for Addiction. 15

Musicians, teachers, and leaders throughout the ages have known and taught

that music is a healing art. There is now a significant body of information and

research among contemporary musicians, educators & researchers verifying

the health and educational benefits of music.

For students, the Benefits have been outlined by Gregory Hochman of

Artdrum.com:

1. Drumming can help students grow academically and improve students'

ability to concentrate and compliment their studies in math, science, language

arts, history, physical fitness and the arts.

2. According to scientific research, playing music, and hence drumming and

playing percussion, increases the development of various regions of the

brain,

3. Playing drums and rhythms can be an optimal experience and encourages

participants of all ages to achieve flow.

4. Drumming is a healing art and therefore it can give participants of any age

a better sense of well being.

5. Hand drumming (and regular participation in any form of percussion

playing) increases the physical stamina of students.

6. Drumming increases body awareness & kinesthetic development;

drumming helps students develop graceful coordination and self-control.

7. Playing rhythms improves listening skills and increases children and teens'

ability to focus for extended periods of time.

8. Generally, the increasing of rhythmic skills - and the learning of any

musical instrument - increases students' confidence.

9. Playing rhythmic music helps students to take notice of the rhythms and

beauty in nature and their surroundings.

10. Drumming in group formats, such as drum circles, bands and orchestras

cultivates an appreciation for teamwork and cooperation.

11. Drum circles are great ethnic and cultural bridges; they

harmoniously bring diverse people, instruments and musical styles together.

12. If parents play or take interest in the musical and learning process of

their children, then drumming can be a means to forge meaningful bonds

between parents and children. 16

Music is right for your children because it provides a healthy, natural and

truly invaluable opportunity for individual expression. It encourages the

development of the whole child by enhancing cognitive, social, physical, and

emotional skills.

OUR OTHER OFFERINGS:

Drum circles for team-building in the workplace. These are effective in

reducing workplace stress and energizing any meeting.

In the west, drum therapy has been embraced and rated effective by top

companies including Toyota, Unilever and Oracle. In an article at NY Times,

the author mentioned that an $11000 program will effectively save the

company in the long run as it lowers employee turnover. In an industry

that spends $30-$60k to find and train a replacement, it’s an investment well

worth it. 17

In Singapore, we are pioneering Drum Circles to become staples in team

building activities in the corporate world.

References:

REFERENCES and ARTICLES:

1

Drum Circles: An Ancient Methodology for a Modern World

- Remo Belli

How group drumming is being used as a tool for wellness and community building

Music is effective because it is a nonverbal form of communication, it is a natural reinforcer, it is

immediate in time and provides motivation for practicing nonmusical skills. Most importantly, it is a

successful medium because almost everyone responds positively to at least some kind of music.

In drum therapy, it’s not about performance, it’s about feeling better. This benefit comes to those who have not

learned how to make their own music.

Drum circles are a cultural phenomenon that have been featured in Time Magazine, Discovery and even Natural

Beauty and Health. Drum circles are probably one of the most ancient forms of community building known to

man.

Here, people come together to create an improvised composition that becomes the score for their own lives. The

drum circle is a platform for musical expression and it is accessible to anyone regardless of age or ability level.

The use of the drum presents for creative expression.

Based upon a recent study, the medical community is beginning to embrace this application of music and

medicine. Dr. Bittman, CEO of the Meadville Medical Center and his research team discovered that a specific

group drumming approach significantly increased the disease fighting activity of circulating white blood cells

(Natural Killer cells) that seek out and destroy cancer cells and virally-infected cells. The study included 111

normal subjects, all of whom were non-musicians. Along with conventional medical strategies, Dr. Bittman

includes group drumming in all of his disease-based programs at the Mind-Body Wellness Center.

Drum circles are happening in many places. This demonstrates the importance of establishing a rhythmaculture

in our Western world. People attend these events not to become better percussionists, but to reduce stress, build

community, and have fun. It is a recreational activity that engages the mind, body, and spirit. Arthur Hull, father

of the modern day drum circle, developed his unique approach to facilitating drum circles in the 1980s through

an observation of the need that extended beyond percussion skill development. According to Arthur, "when we

drum together, it changes our relationships and helps us cope with whatever challenges life hands us."

Drum circles may be seen in corporations for teambuilding, hospitals for music therapy, and music stores for

community building. At the Remo Percussion Center in North Hollywood, we are exploring the application and

value of weekly drum gatherings for social well-being and personal health. A recent survey of sixty participants

showed that the most common reason for attending the weekly drum circles was "stress reduction." The fact that

people are now making their own music for Believing in the need for music making to maintain health

demonstrates a paradigm shift – that musical expression may actually be necessary – more than for

entertainment, but for its health promoting value.

We are focused in integrating drumming and wellness to share information, insights, articles and develop userfriendly instruments that can be used in health care settings globally. Our efforts help people integrate

drumming as a tool for enhancing their lives, reconnecting with their community, and maintaining their health.

http://www.artdrum.com/ESSAY_DRUM_CIRCLES.HTM

2

Drum therapy keeps patients on the (heart)beat

Clara-Rae Genser. Apr. 09, 2004 in COMMUNITY FOLK

Drum your name, we were ordered, and we did, repeating the beat and the name until ordered to stop. Thus

began a four-week study of drum therapy with Miranda Ritterman and her father, Dr. Jeff Ritterman, a

cardiologist at Kaiser in Richmond.

It was fun, relaxing and entrancing, and made for a great feeling of community. And that was the goal,

according to the Rittermans and to Christine Stevens, who flew up from Los Angeles each week to lead the

sessions. From all walks of life, and different backgrounds, by the end of the sessions we knew each other liked

each other a lot. Almost everyone was terribly unhappy when the four-week sessions were over.

The sessions were part of a study to see if drum therapy helps heart patients. As Richmond's pioneers in this

study, we were invited to attend future sessions for cancer patients, to let them know our assessment of drum

therapy.

Miranda Ritterman, a doctoral student at UC Berkeley, had read something about drum therapy and talked with

her father about it. He was interested, and did his own reading on the subject. "He is a much faster reader than I

am," Miranda Ritterman said, "and it was he who found this program of HealthRhythms, a new division within

Remo Inc." Dr. Ritterman's heart patients were invited to take part in the study. Christine Stevens is an

international speaker, music therapist and author. She supplied the drums (many of them bongo drums decorated

with EKGs) and other heart décor.

Through her company, UpBeat Drum Circles, she offers community drum circles for corporate team-building,

diversity training, personal growth, and health and wellness. The major aim is to fight stress, and bring

relaxation and calm. One of the things Christine asked of us was to drum how we felt when we were stressed,

and then, how we felt when we did not feel stressed. The response was dramatic.

The sessions included more than just drumming. There were "shakers" that looked like small apples, with which

we played games in our circle, giggling and laughing. There was a large drum that made sounds likes waves

when moved -- it could be a calm and soothing sound like huge waves breaking on a rocky shore. An important

person during the study was Margie Ginotti, a registered nurse and adult-care manager. She was at every

meeting, and joined in the fun, even leading them when Christine could not. We do not yet know the official

findings of the study, but among ourselves those who participated know that drum therapy is a very positive and

important addition to the world of therapy. Most of us plan to continue on our own in some way.

http://www.djembedirect.com/drumtherapy-article_1.htm

3

Elderly Patients Drum Away the Pain

07.24.08

Paradise View in New York City does not actually have a view, but the long-term care residence in Upper

Manhattan does have a drum circle.

The genesis of the drum circle was about three months ago, when Community Coordinator Paul Padial and

Cantor Daniel Pincus were playing drums in Paradise View's dining room, and they attracted the attention of

residents. "Everybody started coming out to see what all the noise was, and it turned into a dance floor," Padial

says. "We just looked at each other and said, 'This is the coolest thing.'"

Pincus, who is a member of the religious life department at Manhattan Jewish Home Lifecare, the nursing home

of which Paradise View is a unit, and Padial organize a drum circle for residents. Meeting for an hour every

Thursday, it is a success, say staff and residents alike.

The drum circle is part of Jewish Home Lifecare's bid to change what was a conventional nursing home into a

real home for the residents, replete with plenty of activities and choices about when to wake up and what to eat.

The benefits of the drum circle are more than just musical: Pardial says it builds community and provides health

benefits.

"Part of my job is to build community, and drum circles actually mimic a community," he says. "In a drum

circle, every person has a voice. No one person is more important than the other."

The elderly patients who participate can't seem to get enough of making music. One recent drum circle attracted

approximately 30 residents, ranging from ages 65 to 102. They sat waiting for drums or other percussion

instruments to be handed to them. "I love it," the oldest member of the group, Laure Gaeckle, who turns 103 in

February 2009, says. "They started it up, I joined, and I've been drumming ever since."

Gaeckle spends much of her time in bed, and never played the drums before joining the circle. Suffering from

poor eyesight and having difficulty with mobility, drumming provides a welcome diversion. "I wish it would go

on for another hour," she says. "I don't know if I'll be around to play at 103."

At 85, Ernestine Johnston looks like a trendy Manhattanite, with sunglasses, gold earrings, and a pearl bracelet.

While she is not a member of Paradise View, she has been welcomed to the circle. "We just found out about it

and we started coming down. It's new to me so it's fun," Johnston says. "It's very energetic. It really does send

blood through the veins."

Staffers at Paradise View say they are seeing higher energy levels and a boost in morale since drumming

became part of the routine. Music therapists have long used music to connect to people, and especially the

elderly.

"Music is so evocative," says Suzanne Sorel, MT-BC, LCAT, NRMT, director of graduate music therapy at

Long Island, N.Y.-based Molloy College. "Music can kind of supersede all the emotional difficulty and bring

you to an emotional place."

Reaching such a place can be coupled with physical healing, according to some music therapists. "One thing

that drumming can do is access an individual's long- and short-term memory, and decrease agitation," according

to Jane Creagan, MME, MT-BC, the director of professional programs at the American Music Therapy

Association. "Music is sort of a back door that can be used to access parts of the brain that other therapies can't

access."

Unlike speech, music is processed in multiple areas of the brain. The limbic system is activated by the emotional

response to music, while the elements of music, such as rhythm, pitch, and melody, activate other areas of the

brain. Elderly people suffering from the late stages of dementia often show responses to music, including vocal

activity, increased eye contact, changes in facial expression, and physical movement.

The residents at Paradise View are high-functioning and suffer less from dementia than the residents in other

parts of the Jewish Home Lifecare system. The medical director at the nursing home, Richard Neufeld, MD,

says the drum circle could be used with residents who are suffering from dementia. "There is no reason why this

drum circle can't be used in other units with higher dementia," he says. "I'm not sure in a demented unit how

many would participate, but we should try it out."

Neufeld also says that medical research on the health effects of Paradise View's drum circle have not been

tested, but it could "reduce agitation, reduce blood pressure."

Source: Catherine Bilkey/New York Sun

http://www.therapytimes.com/content=0302J84C4896BC8440A040441

5

Education: Music Therapy and Language

Written by Myra J. Staum, Ph.D., RMT-BC

Director and Professor of Music Therapy

Willamette University, Salem, Oregon

Music Therapy is the unique application of music to enhance personal lives by creating positive

changes in human behavior. It is an allied health profession utilizing music as a tool to encourage

development in social/ emotional, cognitive/learning, and perceptual-motor areas. Music Therapy has

a wide variety of functions with the exceptional child, adolescent and adult in medical, institutional and

educational settings. Music is effective because it is a nonverbal form of communication, it is a natural

reinforcer, it is immediate in time and provides motivation for practicing nonmusical skills. Most

importantly, it is a successful medium because almost everyone responds positively to at least some

kind of music.

The training of a music therapist involves a full curriculum of music classes, along with selected

courses in psychology, special education, and anatomy with specific core courses and field

experiences in music therapy. Following coursework, students complete a six-month full time clinical

internship and a written board certification exam. Registered, board certified professionals must then

maintain continuing education credits or retake the exam to remain current in their practice.

Music Therapy is particularly useful with autistic children owing in part to the nonverbal, non

threatening nature of the medium. Parallel music activities are designed to support the objectives of

the child as observed by the therapist or as indicated by a parent, teacher or other professional. A

music therapist might observe, for instance, the child's need to socially interact with others. Musical

games like passing a ball back and forth to music or playing sticks and cymbals with another person

might be used to foster this interaction. Eye contact might be encouraged with imitative clapping

games near the eyes or with activities which focus attention on an instrument played near the face.

Preferred music may be used contingently for a wide variety of cooperative social behaviors like

sitting in a chair or staying with a group of other children in a circle.

Music Therapy is particularly effective in the development and remediation of speech. The severe

deficit in communication observed among autistic children includes expressive speech which may be

nonexistent or impersonal. Speech can range from complete mutism to grunts, cries, explosive

shrieks, guttural sounds, and humming. There may be musically intoned vocalizations with some

consonant-vowel combinations, a sophisticated babbling interspersed with vaguely recognizable

word-like sounds, or a seemingly foreign sounding jargon. Higher level autistic speech may involve

echolalia, delayed echolalia or pronominal reversal, while some children may progress to appropriate

phrases, sentences, and longer sentences with non expressive or monotonic speech. Since autistic

children are often mainstreamed into music classes in the public schools, a music teacher may

experience the rewards of having an autistic child involved in music activities while assisting with

language.

It has been noted time and again that autistic children evidence unusual sensitivities to music. Some

have perfect pitch, while many have been noted to play instruments with exceptional musicality. Music

therapists traditionally work with autistic children because of this unusual responsiveness which is

adaptable to non-music goals Some children have unusual sensitivities only to certain sounds. One

boy, after playing a xylophone bar, would spontaneously sing up the harmonic series from the

fundamental pitch. Through careful structuring, syllable sounds were paired with his singing of the

harmonics and the boy began incorporating consonant-vowel sounds into his vocal play. Soon simple

2-3 note tunes were played on the xylophone by the therapist who modeled more complex

verbalizations, and the child gradually began imitating them.

Since autistic children sometimes sing when they may not speak, music therapists and music

educators can work systematically on speech through vocal music activities. In the music classroom,

songs with simple words, repetitive phrases, and even repetitive nonsense syllables can assist the

autistic child's language. Meaningful word phrases and songs presented with visual and tactile cues

can facilitate this process even further. One six-year old echolalic child was taught speech by having

the therapist/teacher sing simple question/answer phrases set to a familiar melody with full rhythmic

and harmonic accompaniment The child held the objects while singing:

Do you eat an apple? Yes, yes.

Do you eat an apple? Yes, yes.

Do you eat an apple? Yes, yes.

Yes, yes, yes.

and

Do you eat a pencil? No, no.

Do you eat a pencil? No, no.

Do you eat a pencil? No, no.

No, no, no.

Another autistic child learned noun and action verb phrases . A large doll was manipulated by the

therapist/teacher and a song presented:

This is a doll.

This is a doll.

The doll is jumping.

The doll is jumping.

This is a doll.

This is a doll.

Later, words were substituted for walking, sitting, sleeping, etc. In these songs, the bold words were

faded out gradually by the therapist/teacher. Since each phrase was repeated, the child could use his

echolalic imitation to respond accurately. When the music was eliminated completely, the child was

able to verbalize the entire sentence in response to the questions, "What is this?" and "What is the

doll doing?"

Other autistic children have learned entire meaningful responses when both questions and answers

were incorporated into a song. The following phrases were sung with one child to the approximate

tune of Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star and words were faded out gradually in backward progression.

While attention to environmental sounds was the primary focus for this child, the song structure

assisted her in responding in a full, grammatically correct sentence:

Listen, listen, what do you hear? (sound played on tape)

I hear an ambulance.

(I hear a baby cry.)

(I hear my mother calling, etc.)

Autistic children have also made enormous strides in eliminating their monotonic speech by singing

songs composed to match the rhythm, stress, flow and inflection of the sentence followed by a

gradual fading of the musical cues. Parents and teachers alike can assist the child in remembering

these prosodic features of speech by prompting the child with the song.

While composing specialized songs is time consuming for the teacher with a classroom full of other

children, it should be remembered that the repertoire of elementary songs are generally repetitive in

nature. Even in higher level elementary vocal method books, repetition of simple phrases is common.

While the words in such books may not seem critical for the autistic child's survival at the moment,

simply increasing the capacity to put words together is a vitally important beginning for these children.

For those teachers whose time is limited to large groups, almost all singing experiences are

invaluable to the autistic child when songs are presented slowly, clearly, and with careful focusing of

the child's attention to the ongoing activity. To hear an autistic child leave a class quietly singing a

song with all the words is a pleasant occurrence. To hear the same child attempt to use these words

in conversation outside of the music class is to have made a very special contribution to the language

potential of this child.

http://www.autism.com/edu_music_therapy.asp

6

Composite effects of group drumming music therapy on

modulation of neuroendocrine-immune parameters in normal

subjects

Bittman BB, Berk LS, Felten DL, Westengard J, Simonton OC, Pappas J, Ninehouser

M, Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 7 (1): 38-47 JAN 2001

Abstract:

Context Drum circles have been part of healing rituals in many cultures throughout the world since antiquity.

Although drum circles are gaining increased interest as a complementary therapeutic strategy in the traditional

medical arena, limited scientific data documenting biological benefits associated with percussion activities exist.

Objective To determine the role of group-drumming music therapy as a composite activity with potential for

alteration of stress-related hormones and enhancement of specific immunologic measures associated with

natural killer cell activity and cell-mediated immunity.

Design A single trial experimental intervention with control groups.

Setting The Mind-Body Wellness Center, an outpatient medical facility in Meadville, Pa.

Participants A total of 111 age- and sex-matched volunteer subjects (55 men and 56 women, with a mean age of

30.4 years) were recruited.

Intervention Six preliminary supervised groups were studied using various control and experimental paradigms

designed to separate drumming components for the ultimate determination of a single experimental model,

including 2 control groups (resting and listening) as well as 4 group-drumming experimental models (basic,

impact, shamanic, and composite). The composite drumming group using a music therapy protocol was selected

based on preliminary statistical analysis, which demonstrated immune modulation in a direction opposite to that

expected with the classical stress response. The final experimental design included the original composite

drumming group plus 50 additional age- and sex-matched volunteer subjects who were randomly assigned to

participate in group drumming or control sessions.

Main Outcome Measures Pre- and postintervention measurements of plasma cortisol, plasma

dehydroepiandrosterone, plasma dehydroepiandrosterone-to-cortisol ratio, natural killer cell activity,

lymphokine-activated killer cell activity, plasma interleukin-2, plasma interferon-gamma, the Beck Anxiety

Inventory, and the Beck Depression Inventory II.

Results Group drumming resulted in increased dehydroepiandrosterone-to-cortisol ratios, increased natural killer

cell activity, and increased lymphokine-activated killer cell activity without alteration in plasma interleukin 2 or

interferon-gamma, or in the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory II.

Conclusions Drumming is a complex composite intervention with the potential to modulate specific

neuroendocrine and neuroimmune parameters in a direction opposite to that expected with the classic stress

response.

http://www.djembedirect.com/drumtherapy-article_4.htm

7

The Beat of Harmony:

Drumming with Oncology Patients

by Christine K. Stevens, MSW, M.A., MT-BC

Edited by Erin Salez

Harmony - a. the unique blending of two separate tones into one pleasing sound.

Beyond the musical definition, harmony also exists in the sense of community created when a group

makes music together. On a Saturday morning in Santa Monica, California, two separate groups

joined together for an experience that was unique, powerful and impactful. A group of twelve

volunteer drummers from the Remo Percussion Center brought the joy and spirit they found in

drumming to a group of cancer patients at The Wellness Community. In the joining of the two groups,

there was a common chord of health and wellness, achieved through the experience of recreational

music making.

It began with a basket of fruit shakers in the center of a circle. Out of the quiet anxiety of a group of

strangers meeting for the first time, first a chuckle and then some laughter began as one by one,

people chose a shaker and started making music. But it went deeper than that. Participants

commented on the meaning of letting go and giving themselves permission to not be perfect, lessons

important for all of us.

Through a series of rhythm activities geared towards putting people at ease with the process of

making music, the group became more comfortable and relaxed. In one hour, they were playing their

hearts out on the drums, creating moments of expression unrivaled by any words.

The session ended with an experience called guided imagery drumming where participants closed

their eyes and drummed to a story. As a meditative activity, the drumming created a distraction from

the chatter of the critical and worrying mind. After the drum circle, one patient commented that it was

the first time she forgot about her cancer. She began to feel good again.

In the words of Nikki Fiske, a mother, teacher, cancer patient, and a first time drummer?

"It felt so relaxing and freeing to concentrate on the rhythms and be completely in the moment.

Without judgment, without pressure? we each drummed to our own internal rhythms, yet we worked

together as a group to create a unique and harmonious sound. There was a lot of laughter, sharing

and mutual applause. When I left, after two hours of drumming, it was with spirit, heart and courage

lifted up!"

Drumming also has important biological effects. According to a study (111 normal subjects) performed

at the Mind-Body Wellness Center in Meadville, PA, one hour of group drumming following a protocol

entitled, Group Empowerment Drumming™ was shown to significantly increase circulating white

blood cells called natural killer (NK) cells that seek out and destroy cancer and virally infected cells.

(Bittman et al. Alternative Therapy, January, 2001).

James Gordon, MD of the Mind-Body Center in Washington D.C. states "Oncologists should be open

to group drumming if their patients are interested in it. Drumming can put people in a state of

relaxation. It was used as a healing technique 1,000 years ago. Why not now?" (MAMM Magazine,

July/August, 2001)

Remo drum volunteers agreed that they received more from the experience than they gave.

Professional drummer Sam Kestenholtz commented, "Seeing and feeling the spirits of the participants

being lifted as the group played together was an experience like no other. It was like a room full of

strangers became a community of one."

http://www.ubdrumcircles.com/article_oncology.html

------------------------------------------------------------8

Workshop, Saturday, April 16

The power of music

Inspirational… powerful… moving. Investigate how the power of music can transform the way you experience

your daily life, including practical and useful ways in which music can reduce stress and pain, and how using

music intentionally can improve the brain’s ability to focus attention and improve memory. You will leave this

session mentally and musically stimulated, in a good mood, able to better communicate with people, inspired

and feeling hopeful about work and life.

Jennifer Buchanan specializes in the benefits of music in health and education. A professional music therapist,

singer and educator, Jennifer is known for her warm, compassionate use and knowledge of music that builds

people up. Jennifer has witnessed the power of music first-hand developing hundreds of music therapy programs

in Alberta through her well-established company JB Music Therapy Inc. and as past president of the Canadian

Association of Music Therapy.

Jennifer’s music-centered workshop is specifically designed to educate the audience on using music to promote

relaxation at work or at home, attain better focus and improve productivity, assist in finding new inspiration by

igniting creative thinking, unlock important memories and develop meaningful relationships through positive

social music experiences.

Jennifer will be featured at other times throughout the weekend as well.

http://convio.cancer.ca/site/PageServer?pagename=LWCC_SK_sessions

9

The Healing Power of the Drum: Book Review

New York psychotherapist and drum facilitator Robert Lawrence Friedman, writes in his 2000 soft-cover book,

"The Healing Power of the Drum: A Psychotherapist Explores the Healing Power of Rhythm," how individuals

through drumming can attain psychological, physiological and spiritual wellbeing. Clocking in at 208 pages, the

book is both a personal account and an introductory guide to the subject in which he quotes many leading

authorities on their experience drumming in different settings.

"The Healing Power of the Drum" is an easy to read and non-technical book that presents readers with ways

they can achieve increased health benefits from the activity of drumming and shows innovative ways to enhance

their own wellness. The author explores drumming and drums, such as the djembe and conga, from a

multidimensional perspective, explaining the drum's ability to release anger, create joy, alter brain rhythms,

induce trance, and create empowerment. The book includes cutting-edge research how Alzheimer patients have

been able to stay focused for short periods with a drum in their hands. The book also discusses research into

brainwave studies concluding how drumming has positively increased attention span.

Robert Friedman is currently president of Stress Solutions Inc., providing stress-management seminars to

corporate clients and is also affiliated with the St. Barnabas Health Care System in New Jersey.

http://www.x8drums.com/v/blog/2007/04/healing-power-of-drum-book-review.asp

10

Slotoroff, C. 1994. Music Therapy Perspectives, Special Issue: Psychiatric

music therapy. Vol 12, Issue 2. p. 111-116.

Abstract

Describes an improvisational technique that uses drumming and cognitive-behavioral methods to

address issues of power in an experiential and symbolic manner. This drumming technique was

developed in an inpatient short-term psychiatric setting with adults and adolescents who had a history

of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. The author describes the use of this technique with a middleaged woman and an 11-yr-old boy who had been victims of abuse. Although the insights gained and

the increased sense of power and/or self-control during a session will result in lasting, significant

behavioral, cognitive, or emotional changes, the authors suggest that seeds of awareness and of

possibility may be planted. Additionally, this work may serve to inform and support verbal and

nonverbal therapy during and after hospitalization.

Notes

improvisational drumming & cognitive behavioral methods in short term psychiatric setting;

assertiveness & anger management; middle aged female & 11 yr old male survivors of abuse &

trauma

http://www.djembedirect.com/drumtherapy-article_8.htm

11

"Good Vibrations" Interview with David DiLullo (Global Drum

Circles) and Rick Allen (Raven Drum and Def Leppard)

*****by Barbara Stahura*****

The following interview was published in Science of Mind Magazine, April 2010 Issue.

Excerpt reprinted courtesy of Science of Mind Magazine.

Perhaps our innate attraction to rhythm comes from our original exposure in our first home: our

mother’s womb. During the nine months we live there, we are bathed in all manner of sounds from our

mother’s body, most prominently the beat of her heart. Steady and soothing, the heartbeat’s rhythm

surrounds and enfolds us, becoming forever embedded in our psyche and physiology. Even before

birth, we are rhythmic beings.

In addition, nature is full of other rhythms--wave beats on the shore, the circle of day into night and

back again, lunar cycles, the seasons, and much more--while we might not pay them much conscious

attention, they are nevertheless an intrinsic part of us.

Whether a rhythm comes to us from within or without, our instinctive connection with it often moves us

to create our own rhythms--and for that, drumming can’t be beat.

Drumming at its most basic doesn’t require much equipment: a hand or a stick and something hollow

to pound on. Give a toddler a wooden spoon and a pot, and you’ll see--hear--this in joyful, abandoned

action. Yet humans have been drumming with purpose and intention for eons: to make music, to heal

one another, to enhance community, to engage with Spirit. When used therapeutically, drumming

involves all facets of our being, including the physical, emotional, cognitive, psychological, and

spiritual.

Today, serious research is demonstrating how drumming, particularly in drum circles, produces

beneficial results such as antiviral and immunologic effects, stress reduction, better movement after a

stroke or neurological disorder, and even reduction in addictive urges. It can enhance motor

coordination and attention span, reduce anxiety, and help build relationship skills.

Sustained drumming can create the “high” of aerobic exercise because it increases heart rate and

blood flow. It also synchronizes the hemispheres of the brain, causing brain waves on both sides to

entrain, of fall into the same pattern, which can produce effects similar to deep meditation.

Entrainment also occurs among members of the drumming group, bringing about a sense of oneness

and community.

Drummers David DiLullo and Rick Allen know these benefits firsthand. Their drum circles have

attracted hundreds of participants. Before turning to drum circles, DiLullo directed dozens of marching

percussion programs involving up to 100 participants, including the UCLA Marching Band. In 2004, he

became a member of the Center for Spiritual Living in San Jose, California, and a year later took over

management of its music programs.

Fascinated with world drums (drums from many cultures), he soon gathered a “massive collection” of

drums and began wondering what to do with all of them. After attending a drum circle led by Jim

Greiner, a pioneer of community drumming, he knew. He started a drum circle at the center, where

participants use his drums. Now, he also heads Global Drum Circles (golbaldrumcircles.com), the

largest drum circle in Silicon Valley, which recently held a drum circle with 230 attendees. All of their

events in the last eighteen months have sold out. Endorsed as an educator by two drum companies,

he has also worked with the Peninsula Stroke Association in Palo Alto, facilitating therapeutic drum

circles for patients recovering from stroke and brain injury.

DiLullo began playing drums at age fourteen and later became a professional. In his teens, drumming

was simply fun. Now, he says, “Drumming is the way I connect to Spirit. I’ve never been good at

traditional meditation techniques.”

Drum circles can range from totally unfacilitated, where there is no leader and spontaneity reigns, all

the way to extremely structured groups directed by an experienced leader. Many circles are also

targeted to people who already know how to drum. But DiLullo’s are open to everyone, even people

who have never picked up a drum before.

At one of his recent circles, he says that about one-third of the participants had never touched a drum

before and another third had never participated in a drum circle. Yet everyone joined in

enthusiastically, and they are coming back with their friends.

Most people who come to his drum circles don’t realize the benefits of community drumming, at least

at first. They might come out of curiosity or because it looks like fun or to add music-making to their

lives. Then, DiLullo explains, “People get hooked. There’s a sense of community that doesn’t happen

in a concert, for instance. A violin circle would take months to teach the first song.” He laughs as he

imagines this. “But with drumming, it’s instant. You’re making music together in minutes, and

everyone realizes they are now drummers.”

Just the physical act of sitting in a circle enhances the sense of unity with one another, which is

further enlarged to connection with something higher and more universal when everyone is playing

the same rhythm. Sustained drumming, especially in a group, touches a primal, spiritual place in the

participants. DiLullo suspects this has something to do with our ancient cellular memories as well as

physiological responses that occur far below conscious awareness. He believes the vehicle that

carries drummers to an altered state is the vibration, since our bodies vibrate along with the drums

and in a way become drums themselves.

Shamans have known of drumming’s transformative powers for millennia, understanding how it can

take people to an altered consciousness where they can heal. In his drum circles, “People have shifts

in consciousness,” DiLullo explains. “Drumming can be a platform for meditation. And it’s very clear

that people are turning to it as an alternative healing method.”

In contemporary society, we live very much in our head and often ignore our bodies’ subtle sensations

and messages. But with drumming, says DiLullo, “You’re very much in your body, and it takes you to

a place where you can reach your inner-self. Historically, drum circles were used for celebration or

rites of passage, and even today it’s as if we’re still gathering around a fire at night,” he explains.

“Native American shamans called drumming the ‘canoe’ that would carry your consciousness across

the passage [to a spiritual state].”

The ancient practice of drumming for spiritual purposes is beginning a real reemergence today, with a

small but enthusiastic base of drum circle leader eager to bring others into the fold. DiLullo has no

doubts it will continue to grow, comparing to the emergence of yoga in the West. “With drumming, you

can bring music, beat and rhythm into your spiritual practice very easily,” he says.

Like DiLullo, Rick Allen began drumming in his childhood and joined the band Def Leppard on his

fifteenth birthday. But when he was twenty-one, an auto accident ripped away his left arm. At first, he

thought he wouldn’t be able to do much of anything, let alone drum. But then his brother brought a

stereo to his hospital room and played Allen’s favorite bands, like Led Zeppelin and David Bowie.

Almost without thinking, he began tapping out the rhythms with his feet. He realized that all his years

of drumming had made it almost instinctive for him. As he said much later in an interview with

Beliefnet, “All the information was in my head. I just needed to channel it somewhere.”

Before too long, a friend had designed a custom electronic drum kit with pedals for Allen, and he set

about learning to play the high hat, kick drum, snare, and tom-tom with his left foot. In 1986, Def

Leppard played their first big engagement since the accident at England’s Donington Park, where

Allen received a huge welcome back from tens of thousands of fans.

Able to drum again, Allen believed he was fully recovered. But for years he struggled unknowingly to

deal with the energetic trauma his psyche had endured from the accident but never released. When

he met Lauren Monroe in 2000, the deeper healing began.

A healer from childhood, Monroe has studied with Benedictine monks, tribal healers of Brazil, North

America, and New Zealand, and is an initiated minister of Deeksha healing from The Oneness

University in Southern India. She also holds degrees in dance choreography, education, and

massage therapy. She had never been a Def Leppard fan but was familiar with Allen’s story.

“I knew how much suffering and how much bravery was a part of his being and life experience,” she

says. “When he came to me, I felt a lot of things that guided me to work with him in a very spiritual

and energetic way. And I treated this whole person, which includes both of this arms. I don’t think

Rick’s ever had a treatment like that before, but it was important to connect with his arm that wasn’t

there and also into his heart. It was a beautiful experience, and when he left I felt like I had just

worked on some type of spiritual king or something. It was really beautiful.”

Allen was also deeply touched with the intensity of the healing.

“I’d never experienced that kind of massage work before, where you incorporate a physical aspect,

but also the energetic work that can sometimes go along with that,” he says. “And that, for me, was

just profound.”

They married in 2003, but in 2001, they created the Raven Drum Foundation “to educate and

empower individuals and communities in crisis through healing arts programs, drumming events, and

collaborative partnerships,” according to the nonprofit foundation’s Web site (ravendrum.org). Monroe

understood that drumming has been used in healing ceremonies and rituals for millennia. And, as an

experienced drummer himself, Allen understood the power of drumming as an integral part only of Def

Leppard’s music, but of music in general.

“It’s so primal. It’s fantastic,” he says. “Any form of drumming, to me, is…this sounds odd, but it really

becomes a mindless activity because it you allow yourself to fall into it wholly, you kind of disappear.

And time just…oh man, we were just doing that for two hours?”

They began by working with at-risk and incarcerated teens and gang members in the Los Angeles

area, conduction drum circles and healing workshops at juvenile detention centers. But in 2005, they

turned that program over to a staff member and shifted their focus after Allen traveled to Walter Reed

Army Hospital in Washington, D.C., to meet wounded military personnel from the wars in Iraq and

Afghanistan. He visited the amputee ward and the occupational therapy unit. The experience moved

him deeply and inspired him to begin expanding Raven Drum’s work with veterans.

“My own experience with trauma is obviously different from combat trauma, but the way it manifests in

the body is very similar,” he explains. “We’re all different; we process it in a completely different way. I

just find it really, really easy to connect with people. I don’t even have to say anything. I just walk in,

they see my physical form, and immediately they welcome me in a way that is so beautiful. They

make me feel like a warrior. And they allow me to share my experience, and then, ultimately, what

happens is they share their experiences. There’s this wonderful thing that happens where I’m inspired

by them, and they’re inspired by my journey.”

Allen returned to Walter Reed for another visit, and this time Monroe accompanied him.

“After experiencing some of the boys there--and they were boys, very young soldiers--that were

wounded, we just saw the need,” she recalls. “We met their moms or the caretakers or their girlfriends

or their wives, and we saw that this isn’t going to stop soon. We know we can help; we can do

something here. And we came back, and we started working on a plan about how to develop some

programs to share.”

In order to give back to the men and women of the U.S. military, Raven Drum Foundation created an

innovative healing modality, called the Resiliency Program, which included drum circles. It is designed

specifically for current and former military personnel from any war to help them deal not only with

combat-related trauma, but also with the everyday stresses, anxieties, and depression that are

common in military families during wartime. Teens are included with a self-care program designed

specifically for them, and female veterans will soon have their own program.

According to the Raven Drum Web site, new research demonstrates that humans experience

traumatic experience of any kind primarily as a bodily impact. In other words, even if we believe we

have experienced a trauma “only” mentally or emotionally, it still must come through our body to be

experienced at all. And so our body is affected by it, and stores this experience as a memory, just as

it stores all our experiences. After a traumatic event, many people believe that if they do not

consciously think about it, or if they “bury” it, the aftereffects simply will fade away. Unfortunately, this

is not true. The trauma remains “trapped” in the body and can lead to all sorts of dysfunctional coping

mechanisms, such as substance abuse, depression, and worse. It will cause physical, emotional, and

spiritual pain that often deepens over time.

“When you have any kind of traumatic syndrome or crisis in your life,” Monroe explains, “you carry

very intense emotions that, oftentimes, you don’t even know are there”.

Not surprisingly, their drum circles frequently are witness to displays of emotion. Many of the

participants dealing with trauma don’t necessarily know the extent of their hidden negative emotions.

But drumming can help bring them to the surface, where they are released. Participants can trace

their experience of how they felt before the circle again how they felt afterward. “We hear more often

than not that people have less anger or sadness or feelings of depression after experiencing the drum

circle. We also witness a lot of tears from people,” says Monroe.

Allen chimes in to say, “Including me. I’m the crier. I love to rain all over the drum kit, you know? But

it’s so beautiful, it really is. It’s, again so experiential you can’t necessarily explain it. It’s like you just

feel this wave of grace and it does something really profound. You go into the gratitude.”

http://www.globaldrumcircles.com/druminterview.cfm

12

Drumming helps your brain and your health

When I was a kid, watching Ringo Starr play the drums inspired me to be a drummer. He looked like

he was having a blast! At rock concerts, I always watch the drummer, pounding away in multiple

rhythms, holding the beat for everyone else. I’m lucky I can carry even one rhythm—which explains

why I’m not a rock drummer—but I have attended drum circles where no experience or talent is

required. All that’s needed is the desire to make some rhythmic noise in community with

others. If you haven’t tried a drum circle, I hope you have the opportunity one day. It’s magical, as

drummers David DiLullo and Rick Allen can attest. In addition to having fun, people in their

drum circles come for meditation, stress reduction, healing, and transformation.

David runs Global Drum Circles in California’s Bay Area, and some of the participants have been

people with brain injury or stroke, a few of whom were brought by their neurologists.

David says drum circles are helpful for people with various brain injuries because “there’s an

exercising of the brain. It takes a lot of coordination between the right and left hemispheres. When

your right and left hands are doing something in a synchronized manner, you’re promoting balance

between the hemispheres.”

In addition, he explains that you’re doing something physical that “takes you out of your analytic brain

space. And going beyond that is the healing nature of vibration. Drumming is music therapy. You’re

bathing all the cells of your body in this vibration.”

He’s led a circle for the Peninsula Stroke Association, of Palo Alto. He reports that even

participants who had the use of only one arm did a great job keeping up with the rhythms. One

stroke survivor with partial paralysis said drumming in the circle allowed him to forget about his

affliction for the first time.

Especially for people who have had a stroke or brain injury, being part of a drum circle offers

the opportunity to have some fun while building up their confidence again. “Drumming is easy,”

says David. “If they can’t dance or play baseball, drumming is a wonderful way to feel active, and

they’re part of a group joined in the same activity.”

Rick Allen is the drummer for Def Leppard. As the result of an auto accident in the 1980s, he has

only one arm. But with a customized drum kit, he learned to use his left foot to take the place of his

missing left arm. In 2001, he and his wife, Lauren Monroe, created Raven Drum Foundation “to

serve, educate and empower veterans and people in crisis through the power of the

drum.” Their major project now is the Resiliency Program, which is an innovative healing program for

veterans, active duty military, and their families.

The Raven Drum Web site outlines some of the therapeutic benefits of drumming. On the

physical side, these include production of the body’s own pain killers, boosting the immune system,

control of chronic pain, and relief of stress and anxiety. In addition, drumming with a group adds the

benefits of creating a sense of connectedness with others and feeling oneself flowing with the natural

rhythms of life.

Joining in a drum circle can be fun and beneficial for anyone. Yet for people with brain injury, it can

offer a unique kind of healing experience not available anywhere else.

Today’s journaling exercises:

If you’re ready to do some private writing in your journal, choose one or more of these prompts to get

started. Try to write for at least five minutes.

If you’ve had a brain injury:

• My favorite kind of music is _________________ because…

• One thing I do to help me feel more connected to other people is…

If you’re a family caregiver:

• One of my favorite memories connected to music is… (See how much sensory detail you can

include. In addition to the music you heard, what did you see, touch, taste, and smell? How did all of

your senses contribute to this memory?)

http://journalafterbraininjury.wordpress.com/2009/11/20/drumming-helps-your-brainand-your-health/

13

Drums Of Illumination

A Frame Drum Roundtable With

Alessandra Belloni, Judy Piazza, And Miranda Rondeau

By Diane Gershuny Originally published in DRUM! Magazine’s March 2010 Issue

Shrouded in mystery, the frame drum can be traced back to the Paleolithic era, and has been

historically used as an ancient technology to alter consciousness in spiritual ritual. Images of women

playing the frame drum are pervasive in artifacts of goddess traditions from ancient civilizations in the

Near East, India, Greece, Rome, and other parts of the world.

Last November, internationally renowned tambourine virtuoso, singer, dancer, actress, and author

Alessandra Belloni brought together a group of kindred women frame drummers in a weekend

workshop and evening concert at Remo’s Recreational Music Center in North Hollywood to honor the

feminine and the healing power of the frame drum.

The group included devotional singer/frame drum artist and teacher Miranda Rondeau and Judy

Piazza, a multi-instrumentalist, workshop facilitator, recording artist, and educator who teaches the

Egyptian riq and has performed on many frame drums from various cultures.

We gathered together Belloni, Piazza, and Rondeau to talk about the history of the frame drum, and

how they learned from — and broke with — tradition in their own work.

DRUM! What inspired you to bring together these specific women artists?

BELLONI I had been conceiving of this event for a long time and chose a unique ensemble of women

artists who I believed were very different and all had the power to summon feminine power with frame

drums, voice, and ritual dance from ancient healing and musical traditions around the world, including

southern Italy, Brazil, Asia, and the Middle East. They were all my best students and they each took

their own path musically and artistically. I think we created a fiery global percussive journey in honor

of the feminine principle, for women and men alike. The workshop participants were taken by the

different skills and knowledge each woman had to offer, and the audience really loved the concert as

they all danced with us at the end.

DRUM! How did each of you take what you learned from Alessandra and apply that to your playing?

PIAZZA I met Alessandra early on in my drumming. I took her workshop in Vermont at a camp fair. I

was in a transitional point in my life. I had been a musician of many other instruments, and still am,

but the drums really shifted things in me. My first teacher and inspiration was Glen Velez, and then to

see a woman who had taken this path and was so proficient and passionate about living her gift in the

world, really inspired me.

BELLONI And that was great to see, too, because Glen Velez was my first student and he inspired

me to continue this path.

RONDEAU I started playing the frame drum 15 years ago, after I first saw Layne Redmond perform.

She gave a slide presentation of women playing the frame drum throughout history, and when I saw

that my heart cried out. It was like a homecoming. There was something familiar in seeing women

playing the drums. She was my first teacher, and then someone gave me an article that Alessandra

had written. When I read it I was crying because I was resonating with what she was speaking about

and I knew that I had to take her workshop. When she plays I feel the room fill up with the energy of

women drummers from ancient times.

DRUM! What is the connection between women and frame drums?

BELLONI The instrument goes back to prehistoric times. They were used mainly by women to honor

the goddesses and to heal the community, because they are highly spiritual, very feminine, and are

connected to the Moon and the Earth. We believe it was mainly a matriarchal society. The Earth

goddess, Cybele, was a very potent goddess from Anatolia [Turkey] who is also worshipped in

ancient Greece and Rome. The legend is that she was made from a black meteorite that fell from the

stars and is now worshipped as the “Black Madonna.” I was born in Rome where you can see still

frescos of Cybele with a frame drum or women holding a round instrument, not necessarily like a

tambourine, but with the skin and the frame. The tambourines were very popular in ancient Greece

and the women would use them to induce trance in their rites. They are now still used in southern Italy

ceremonies honoring the Black Madonna in the tammurriata. I’m really proud of the fact that I was

born in southern Italy and the tradition has never died there.

DRUM! Each of you plays multiple instruments, but what drew you to the drum specifically?

PIAZZA I had a total insatiable curiosity about women and frame drums and how they were

connected. The frame drum, in a broader sense, was so totally integral to healing, for men and for

women, because of it bringing alive the feminine aspect of our human nature. It’s much more subtle

— there’s a fluidity and motion with the drum unlike some of the larger drums. To use the healing

aspect of rhythm to connect to the mother, to the Earth, to all the elementals, became very important

to me, especially in my work as a music therapist.

RONDEAU I got into drum circle drumming at a [Grateful] Dead show, and I was magnetized. But I

dance — I didn’t think to drum. It wasn’t until I read Mickey Hart’s book, Drumming At The Edge Of

Magic. There’s a section where he talks about the technical side and the spiritual side, and in a way,

that gave me permission to play the drum. Inside my head, there was conditioning that said drumming

is for men. Later I saw Layne Redmond play, and I knew I was supposed to be playing this

instrument. I realized, too, that I had a lot of other conditioned, collective thoughts about women —

that they are inferior — and I carried that around. Healing began as I learned about the connection

between the drum and the divine feminine. The sound echoes the mother’s heartbeat. Its archetypal

shape represents wholeness, unity, and oneness. Like Judy was saying, the drum connects me to the

Mother and the Earth and elements that sustain us. This gave me new thought patterns about

women. Wendy Griffin, a women studies professor at Cal State Long Beach, created a group called

Lipushiau, [who was] the first written, named drummer in history, a high priestess. And our first gig

was a women’s conference at the university. All changed my life.

DRUM! How are you breaking boundaries in technique and approach?

BELLONI I’ve taken the Italian style into other rhythms. Traveling to Brazil was a big part of it. I

realized that the technique that is very loud and strong was perfect for Brazilian rhythms, and could be

heard over other instruments. I designed a Tam Brush for Pro-Mark that I use together with the

tambourine, so it keeps the sound of the drum. In my case, working with Glen [Velez] and other great

drummers, like Rick Allen from Def Leppard, I feel like I’m absorbing everything and using it in my

music. But mainly my playing style is a Latin American art with Brazilian rhythms.

PIAZZA I’ve been a part of the Arab community in Michigan, after moving there 25 years ago before I

came to California. I met a master Lebanese oud player and he asked me to play with him. I thought,

What are you thinking to ask a white woman to play in a traditional Lebanese situation? He got

flustered and said to me, “Music is not of the country, it’s of the heart.” This changed my life and took

me another huge step in becoming at peace as a white woman who is insatiably obsessed with the

drums. He gave me permission in a way, and had a lot to do with my own shifting and confidence in

playing out, and in feeling that I could. I was making beautiful music and people were responding. I

remember saying to Glen that I’d only been playing two years, and I had no business teaching. He

told me to just share what you know. I play in various settings and styles now, including

Andalusian/hip-hop fusion, yoga classes, kirtan or devotional music gatherings, women’s music

festivals, solo concerts, retreats, and festivals in and out of the country.

RONDEAU I think what I add the most is the vocals. There are not many people that are drumming

and singing. My vocal style transcends language, bypasses the intellect, and is devotional and

invoking in nature. I like the melodic part of the drum, and because I sing, I like to experiment with

where the different tones are in the drum. I’ve explored different ways to hit in two different places to

get the tone that I want and from there is where the music is inspired. As far as playing situations, I

open up for many consciousness-raising events as well as play for baby and bridal showers to

birthday rituals to funerals and memorials. I also work a lot with different goddess communities,

playing for their rituals to create a peaceful, meditative space as well as playing for dance and

kundalini yoga classes, and working with kids. I like sharing the frame drum and getting people

related to what it is. When I perform I try to make it participatory to initiate people to the possibility of

playing.

BELLONI Sometimes it can be two things. Unfortunately, because of my style, which is so powerful, it

can be inspiring to some and intimidating to others. I really want to turn that around and make it

accessible.

PIAZZA Like Miranda, I work with children as well. I think all of us have this in common, as far as

using the drum to connect and synergize, and with that synergy, we go deeper down the path of

rhythm at every level in our being. Children often have never seen drums played in this way. It’s

amazing what happens from that: Young people become inspired in their own modes of expression —

a seed is planted. Recently I heard from a student that was into head-banging music when I knew

him. He reached out to tell me how deeply he had been influenced by our time together in high

school.

DRUM! Is there a definitive technique involved with playing the frame drum or is it very much

individualistic?

BELLONI You have to start with the basics, whether it’s southern Italian, Brazilian, Irish, or South

Indian, and then take that technique and make it your own.

PIAZZA And there has absolutely been a lot of fusing of cultural styles.

DRUM! How has the technique evolved through that fusing?

BELLONI Glen Velez was the one to make everyone look at that. He took technique from many other

countries and made it his own. I think he deserves to be recognized because there’s a credible,

feminine energy coming from him that is not macho at all. Even though he was my first student and

we played together in a duo for many years, I learned a lot from him as far as technique. If it weren’t

for Glen, a lot of people wouldn’t be doing this right now.

DRUM! Are there other players carrying on the tradition and breaking new ground?

PIAZZA There are more and more people frame drumming, whether they’re carrying on the tradition

or making it their own.

BELLONI Like Layne Redmond — she was also inspired by Glen and is making it her own.

PIAZZA Rowan Storm.

BELLONI In Brazil, I know lots of them.

PIAZZA And that’s just it, for every one of us who have earned some recognition, there’s hundreds

back in the culture that are fantastic and that we’ve been inspired by, that have not received any

acknowledgment

http://www.drummagazine.com/handdrum/post/drums-of-illumination/

14

Complementary Therapy for Addiction: 'Drumming Out Drugs'

Winkelman, Michael, American Journal of Public Health; Apr2003, Vol. 93 Issue 4,

p647, 5p

Objectives. This article examines drumming activities as complementary addiction treatments and

discusses their reported effects.

Methods. I observed drumming circles for substance abuse (as a participant), interviewed counselors

and Internet mailing list participants, initiated a pilot program, and reviewed literature on the effects of

drumming.

Results. Research reviews indicate that drumming enhances recovery through inducing relaxation

and enhancing theta-wave production and brain-wave synchronization. Drumming produces

pleasurable experiences, enhanced awareness of preconscious dynamics, release of emotional

trauma, and reintegration of self. Drumming alleviates self-centeredness, isolation, and alienation,

creating a sense of connectedness with self and others. Drumming provides a secular approach to

accessing a higher power and applying spiritual perspectives.

Conclusions. Drumming circles have applications as complementary addiction therapy, particularly for

repeated relapse and when other counseling modalities have failed. (Am J Public Health.

2003;93:647-651)

Recent publications(n1-n8) reveal that substance abuse rehabilitation programs have incorporated

drumming and related community and shamanic activities into substance abuse treatment. Often

promoted as "Drumming out Drugs," these programs are incorporated in major rehabilitation

programs, community centers, conference workshops and training programs, and prison systems.

Although systematic evaluations of the effectiveness of drumming activities are lacking, experiences

of counselors and clients indicate that drumming can play a substantial role in addressing addiction.

Evidence suggesting that drumming enhances substance abuse recovery is found in studies on

psychophysiological effects of drumming(n9-n13) and the therapeutic applications to addictions

recovery of altered states of consciousness,(n14) meditation,(n15-n19) shamanism,(n20-n21) and

other shamanic practices.(n22-n24)

METHODS

This report is based on information acquired from observations of drumming activities in substance

abuse programs; interviews with program directors and counselors about the effects and experiences

induced; a pilot program introducing drumming for recovering addicts; and on-line discussions and

published material on drumming effects. Because of confidentiality issues, the programs observed did

not permit interviews with clients. Clients' perspectives were provided by the directors and counselors

involved in the program.

RESULTS

The following summarizes research done during 2001 on programs in Pennsylvania, Virginia,

Wisconsin, and Missouri. Participant observation was carded out in the first 2 locations; interviews

and published material were used for descriptions of activities and assessment of their effects at all

sites.

Mark Seaman and Earth Rhythms of West Reading, Pa

Seaman is recovering from addiction; he began drumming as a way to express himself and become

part of a community. He was searching for natural altered states of consciousness. His engagement

with drums led to a personal transformation and an involvement with the recovery industry through

counselors he knew at the Caron Foundation in Wernersville, Pa.(n3) They wanted to expose

adolescents in substance abuse treatment to drumming. The counselors said that these shut-down,

angry, disenfranchised youth came alive as drumming gave them an avenue of expression. Initially,

his programs were closely tied to the therapeutic process. Now, however, they are offered as

recreational activity, and use drumming to create healing energy.

Activities. Seaman's programs begin with his drumming as people enter the room. They pick up

drums and are free to play them as they choose. He then introduces warm-up exercises to make

people feel comfortable with the drums, teaching people how to hit the drums without emphasizing

anything technical. A vocal element is introduced to engage the group in coordinated chanting/singing

activities to get their energy going. He allows people to play spontaneously to lay the groundwork for

nonverbal communication and asks participants to show how they feel through playing a rhythm on

the drums. Call-and-response activities are used to connect the group. A subsequent activity gives

each participant the opportunity to briefly use the dram to express feelings. The group engages in the

creation of improvisational music that produces a feeling of great accomplishment and engages a

"letting go" process through visualization. Seaman ends his program with an application of the

Alcoholics Anonymous' 11th step (meditation), using meditation music and a variety of percussion

instruments to reinforce a visualization process to connect with a higher power. "I get people relaxed,

give them permission to leave their body and go on a journey. I talk about forgiveness, acceptance

and surrender. I work [on] release of guilt from the wreckage that they have produced through their

addictions. The visual imagery connects with the inner child, to release baggage, to awaken true

potential, to image contact with higher power that covers and embraces them in a space of joy and

healing."

Effects. The participants enthusiastically receive the drumming. Staff emphasized that the youths

particularly need drumming when group dynamics are stressed because of conflict within the group,

and when the group's sense of unity and purpose is disrupted by a client's relapse to drugs. Seaman

finds that drumming pulls a group together, giving a sense of community and connectedness. The

terminal meditation activity induces deep relaxation, eases personal and group tensions, and often

leads to strong emotional release. Seaman suggests that drumming produces an altered state of

consciousness and an experience of a rush of energy from the vibrations, with physical stimulation

producing emotional release. Because addicted people are very self-centered, are disconnected, and

feel isolated even around other people, the drumming produces the sense of connectedness that they

are desperate for, he says. "All of us need this reconnection to ourselves, to our soul, to a higher

power. Drums bring this out. Drums penetrate people at a deeper level. Drumming produces a sense

of connectedness and community, integrating body, mind and spirit." Seaman's program is designed

to induce a spiritual experience that is upbeat and fun. Meditation, "letting-go," and "rebirthing

experiences" allow people to leave behind the things they don't want (e.g. their addictions) and

engage the themes of recovery within the dynamics of group drumming.