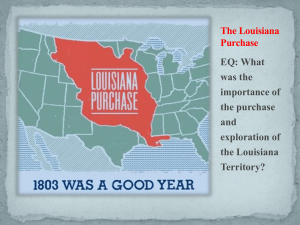

The Louisiana Purchase (1803)

advertisement

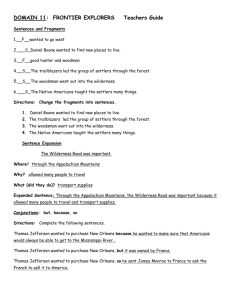

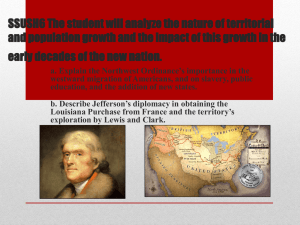

The Louisiana Purchase http://www.monticello.org/site/jefferson/louisiana-purchase The Louisiana Purchase (1803) was a land deal between the United States and France, in which the U.S. acquired approximately 827,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River for $15 million dollars. "This little event, of France's possessing herself of Louisiana, is the embryo of a tornado which will burst on the countries on both sides of the Atlantic and involve in it's effects their highest destinies." 1805 Map of Louisiana by Samuel Lewis; courtesy the Library of Congress President Thomas Jefferson wrote this prediction in an April 1802 letter to Pierre Samuel du Pont amid reports that Spain would retrocede to France the vast territory of Louisiana. As the United States had expanded westward, navigation of the Mississippi River and access to the port of New Orleans had become critical to American commerce, so this transfer of authority was cause for concern. Within a week of his letter to du Pont, Jefferson wrote U.S. Minister to France Robert Livingston: "Every eye in the U.S. is now fixed on this affair of Louisiana. Perhaps nothing since the revolutionary war has produced more uneasy sensations through the body of the nation." Background The presence of Spain was not so provocative. A conflict over navigation of the Mississippi had been resolved in 1795 with a treaty in which Spain recognized the United States' right to use the river and to deposit goods in New Orleans for transfer to oceangoing vessels. In his letter to Livingston, Jefferson wrote, "Spain might have retained [New Orleans] quietly for years. Her pacific dispositions, her feeble state, would induce her to increase our facilities there, so that her possession of the place would be hardly felt by us." He went on to speculate that "it would not perhaps be very long before some circumstance might arise which might make the cession of it to us the price of something of more worth to her." Napoleon Bonaparte; courtesy the Library of Congress Jefferson's vision of obtaining territory from Spain was altered by the prospect of having the much more powerful France of Napoleon Bonaparte as a next-door neighbor. France had surrendered its North American possessions at the end of the French and Indian War. New Orleans and Louisiana west of the Mississippi were transferred to Spain in 1762, and French territories east of the Mississippi, including Canada, were ceded to Britain the next year. But Napoleon, who took power in 1799, aimed to restore France's presence on the continent. The Louisiana situation reached a crisis point in October 1802 when Spain's King Charles IV signed a decree transferring the territory to France and the Spanish agent in New Orleans, acting on orders from the Spanish court, revoked Americans' access to the port's warehouses. These moves prompted outrage in the United States. 1815 Plan of New Orleans by I. Tanesse; courtesy the Library of Congress While Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison worked to resolve the issue through diplomatic channels, some factions in the West and the opposition Federalist Party called for war and advocated secession by the western territories in order to seize control of the lower Mississippi and New Orleans. Negotiations Aware of the need for action more visible than diplomatic maneuvering and concerned with the threat of disunion, Jefferson in January 1803 recommended that James Monroe join Livingston in Paris as minister extraordinary. (Later that same month, Jefferson asked Congress to fund an expedition that would cross the Louisiana territory, regardless of who controlled it, and proceed on to the Pacific. This would become the Lewis and Clark Expedition.) Monroe was a close personal friend and political ally of Jefferson's, but he also owned land in Kentucky and had spoken openly for the rights of the western territories. Jefferson urged Monroe to accept the posting, saying he possessed "the unlimited confidence of the administration and of the western people." Jefferson added: "All eyes, all hopes, are now fixed on you, for on the event of this mission depends the future destinies of this republic.” Shortly thereafter, Jefferson wrote to Kentucky's governor, James Garrard, to inform him of Monroe's appointment and to assure him that Monroe was empowered to enter into "arrangements that may effectually secure our rights & interest in the Mississippi, and in the country eastward of that." As Jefferson noted in that letter, Monroe's charge was to obtain land east of the Mississippi. Monroe's instructions, drawn up by Madison and approved by Jefferson, allocated up to $10 million for the purchase of New Orleans and all or part of the Floridas. If this bid failed, Monroe was instructed to try to purchase just New Orleans, or, at the very least, secure U.S. access to the Mississippi and the port. But when Monroe reached Paris on April 12, 1803, he learned from Livingston that a very different offer was on the table. Napoleon's plans to re-establish France in the New World were unraveling. The French army sent to suppress a rebellion by slaves and free blacks in the sugar-rich colony of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti) had been decimated by yellow fever, and a new war with Britain seemed inevitable. France's minister of finance, Francois de Barbé-Marbois, who had always doubted Louisiana's worth, counseled Napoleon that Louisiana would be less valuable without Saint Domingue and, in the event of war, the territory would likely be taken by the British from Canada. France could not afford to send forces to occupy the entire Mississippi Valley, so why not abandon the idea of empire in America and sell the territory to the United States? Napoleon agreed. On April 11, Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand told Livingston that France was willing to sell all of Louisiana. Livingston informed Monroe upon his arrival the next day. Seizing on what Jefferson later called "a fugitive occurrence," Monroe and Livingston immediately entered into negotiations and on April 30 reached an agreement that exceeded their authority - the purchase of the Louisiana territory, including New Orleans, for $15 million. The acquisition of approximately 827,000 square miles would double the size of the United States. Though rumors of the purchase preceded notification from Monroe and Livingston, their message reached Washington in time for an official announcement on July 4, 1803. The purchase treaty had to be ratified by the end of October, which gave Jefferson and his Cabinet time to deliberate the issues of boundaries and constitutionality. Exact boundaries would have to be negotiated with Spain and England and so would not be set for several years, and Jefferson's Cabinet members argued that the constitutional amendment he proposed was not necessary. As time for ratification of the purchase treaty grew short, Jefferson accepted his Cabinet's counsel and rationalized: "It is the case of a guardian, investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory; and saying to him when of age, I did this for your good.” The Senate ratified the treaty on October 20th by a vote of 24 to 7. Spain, upset by the sale but without the military power to block it, formally returned Louisiana to France on November 30th. France officially transferred the territory to the Americans on December 20th, and the United States took formal possession on December 30th. Jefferson's prediction of a "tornado" that would burst upon the countries on both sides of the Atlantic had been averted, but his belief that the affair of Louisiana would impact upon "their highest destinies" proved prophetic indeed. Louisiana Purchase http://geography.about.com/od/historyofgeography/a/louisianapurcha.htm On April 30, 1803 the nation of France sold 828,000 square miles (2,144,510 square km) of land west of the Mississippi River to the young United States of America in a treaty commonly known as the Louisiana Purchase. President Thomas Jefferson, in one of his greatest achievements, more than doubled the size of the United States at a time when the young nation's population growth was beginning to quicken. The Louisiana Purchase was an incredible deal for the United States, the final cost totaling less than five cents per acre at $15 million (about $283 million in today's dollars). France's land was mainly unexplored wilderness, and so the fertile soils and other valuable natural resources we know are present today might not have been factored in the relatively low cost at the time. The Louisiana Purchase stretched from the Mississippi River to the beginning of the Rocky Mountains. Official boundaries were not determined, except that the eastern border ran from the source of the Mississippi River north to the 31 degrees north. Present states that were included in part or whole of the Louisiana Purchase were: Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming. Historical Context of the Louisiana Purchase As the Mississippi River became the chief trading channel for goods shipped among the states it bordered, the American government became greatly interested in purchasing New Orleans, an important port city and mouth of the river. Beginning in 1801, and with little luck at first, Thomas Jefferson sent envoys to France to negotiate the small purchase they had in mind. France controlled the vast stretches of land west of the Mississippi, known as Louisiana, from 1699 until 1762, the year it gave the land to its Spanish ally. The great French general Napoleon Bonaparte took back the land in 1800 and had every intention of asserting his presence in the region. Unfortunately for him, there were several reasons why selling the land was all but necessary: A prominent French commander recently lost a fierce battle in Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) that took up much needed resources and cut off the connection to the ports of North America’s southern coast. French officials in the United States reported to Napoleon on the country's quickly increasing population. This highlighted the difficulty France might have in holding back the western frontier of American pioneers. France did not have a strong enough navy to maintain control of lands so far away from home, separated by the Atlantic ocean. Napoleon wanted to consolidate his resources so that he could focus on conquering England. Believing he lacked the troops and materials to wage an effective war, the French general wished to sell France's land to raise funds. And so, Napoleon rejected America's proposal to purchase New Orleans, choosing instead to offer the entirety of France's North American possessions as the Louisiana Purchase. Led by U.S. Secretary of State James Madison, American negotiators took advantage of the deal and signed on the President's behalf. Back in the United States the treaty was approved in Congress by a vote of twenty-four to seven. Lewis and Clark Journals (Go online and read and review this web site) http://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/ The Louisiana Purchase did not prompt the expedition to explore west of the Mississippi; Lewis was already on his way across the Appalachians in the summer of 1803 when Jefferson sent him definite word of the diplomatic windfall that had occurred in Paris the previous April. Jefferson's hopes had always pointed toward eventual American penetration of the lands beyond the Mississippi, but the French decision to sell this vast territory presented the United States with an opportunity of which the president could only have dreamed for the distant future. Now an expedition became all the more important as an inspection and an assertion of sovereignty over the new empire. [9] Jefferson and Lewis agreed that there must be a second-in-command competent to carry on if something were to happen to the commander; Lewis's choice was his old army friend William Clark. Four years older than Lewis, he had also served several years in the army on the frontier and had been Lewis's immediate superior for a time. After resigning his captain's commission in 1796, he had engaged in family business in Kentucky and Indiana. Clark had visited Lewis in Washington and had made Jefferson's acquaintance. In accepting Lewis's offer, Clark wrote, "The enterprise &c. is Such as I have long anticipated"; his words suggest that the two friends had discussed the possibility of such an expedition, and that Jefferson may have earlier given them both some hint of his plans. [10] Jefferson had much more in mind, however. The captains were to open a highway for the American fur trade, to win over the Indians from Spanish or British influence, and to lay the foundation for what Jefferson hoped would be a carefully regulated trade and intercourse with the Indians that would avoid some of the evils of unrestrained competition and interracial conflict so common in American experience. Further, they were to observe and record the whole range of natural history and ethnology of the area and the possible resources for future settlers. Jefferson expected a great deal of two infantry officers, but they met the challenge. [14] Lewis, a student of plants and animals since boyhood, made significant additions to zoological and botanical knowledge, providing the first scientific descriptions of many new species. Only in recent decades have his contributions been fully appreciated. The captains also made the first attempt at a systematic record of the meteorology of the West and less successfully attempted to determine the latitude and longitude of significant geographical points. [15] Jefferson's instructions also reflected his lifelong interest in ethnology, and in carrying them out Lewis and Clark displayed an objectivity and tolerance rare in their generation. Lacking the conceptual tools of the modern anthropologist, they nonetheless provided the first general survey of the life and material culture of the village Indians of the Missouri, the Rocky Mountain tribes, and those of the Northwest Coast. They also achieved, on the whole, a record for peaceful cooperation with the Indians that few of their predecessors or successors could equal. [16] Lewis crossed the Appalachians in the summer of 1803, supervised the construction of his keelboat in Pittsburgh, and started down the Ohio on August 31. He picked up Clark at Clarksville, Indiana, and gathered the first of their recruits. Both leaders were commissioned officers in the army, and most of their men were enlisted in the army, some signed up especially for the trip, others already in the service and detailed for the expedition by their commanding officers. Lewis expected that Clark would hold the same captain's rank as he, but red tape in the Department of War resulted in Clark's receiving only a second lieutenant's commission. They concealed this embarrassing fact from the men, and Clark is always "Capt. C." in Lewis's journals. There was no disturbance in their remarkably harmonious relationship, and Lewis apparently treated Clark as "equal in every point of view," a partner whose abilities were complementary to his own. Nonetheless the situation irked Clark, who had been a captain in his earlier period of service and Lewis's superior officer. After the expedition's return he sent the commission back to the secretary of war as soon as possible, remarking that it had served its purpose, and in later years he concealed his lower official status from all but a few. [19] A long winter's stay across from St. Louis, at River Dubois in Illinois, waiting for spring and for the transfer of Louisiana to the United States, enabled the captains to gather their men, evaluate and discipline them, and collect some additional information—notably the personal advice of James Mackay and the Missouri River maps of John Evans (Atlas maps 7– 12). By the spring of 1804 they had eliminated a few less desirable recruits, had given the rest some idea of what was expected of them, and were ready to begin the great adventure. For the first stage of the journey, as far as the Mandan villages, they followed the footsteps of others. There were maps of the route, however sketchy, and the Indians had had some acquaintance with traders. In this period the captains devoted much time to informing the Indians of the change of sovereignty, to insuring as much as possible that the Indians transferred their nominal allegiance, and to alleviating intertribal conflicts. The journey was marred in this period by some disciplinary problems, by the death of Sergeant Charles Floyd—the only man of the Corps who died on the trip—near present Sioux City, Iowa, and by their nearly violent encounter with the Teton Sioux near present Pierre, South Dakota. They passed the winter of 1804–5 at Fort Mandan, near the Mandan and Hidatsa villages in North Dakota; the wait for the Missouri to thaw allowed them to gather much information from the Indians on the geography as far as the Missouri headwaters. In April 1805, they sent back their heavy keelboat and some enlisted men and "proceeded on" up the Missouri in canoes and pirogues. With them now was the Shoshone woman Sacagawea, with her husband Toussaint Charbonneau and their infant son Jean Baptiste. More than four months of travel, including a month-long portage of the Great Falls of the Missouri, ended at the Continental Divide on the Montana-Idaho border, with the dawning realization that the portage to the waters of the Columbia would not be the simple matter they had hoped. [20] Promises of guns and trade maintained the expedition's friendly relations with the Shoshones; in exchange, the captains secured horses and guides for the trip across the mountains. They could not have known it beforehand, but they had come to one of the most difficult places for crossing the Rockies, and they had barely enough time to make the trip before winter closed the trails. After a cold, hungry trek across what Sergeant Patrick Gass called "this horrible mountainous desert," they reached the country of the Nez Perces on the Clearwater River in Idaho; there they built canoes and hurried on down the Clearwater, the Snake, and the Columbia to the Pacific. [21] All the way from Fort Mandan they had journeyed through country known only to the native inhabitants, until they neared the mouth of the Columbia and reentered the world of known geography. Clark's note of November 7, 1805: "Ocian in view! O! the joy," though premature, expressed the emotions of them all. They passed a dreary, damp winter at Fort Clatsop, on the Oregon side of the Columbia estuary, knowing that snow would delay their returning earlier. Nonetheless, they accomplished considerable scientific work there, and the journals are rich with ethnographic and natural history materials. Jefferson had considered the possibility of at least part of the party returning by sea, if they should meet any trading vessels on the coast. The captains had apparently abandoned this idea, and in any case they met no ships, though evidence of white contact with the local people was abundant. On March 23, 1806, they began their return by canoe and horseback, delaying a month among the Nez Perces in Idaho waiting for the snow to melt in the Bitterroot Mountains. Having crossed the Bitterroots, they split the party. So confident were they now of their ability to survive that they separated in order to add to their geographical knowledge. Lewis crossed the Continental Divide to the northeast to find a shorter passage over the mountains and to explore the Marias River in present Montana, while Clark went southeast to travel down the Yellowstone. Lewis's trip led him to a tragic encounter on the Marias in which he and his men killed two Blackfeet, the only real violence of the trip. Clark's journey was relatively uneventful. Reunited in North Dakota, Lewis and Clark again visited the Mandan and Hidatsa villages, left Sacagawea, Charbonneau, and young Jean Baptiste there, and hurried on down the Missouri to St. Louis. Traders along the way told them that virtually everyone had given them up as lost, rumor asserting that they were dead at the hands of Indians or that "the Spanyards had us in the mines &C.," in Sergeant John Ordway's words. [22] Only the president still retained some hope. They arrived at St. Louis on September 23, 1806; three days later Clark closed his journal on an anticlimactic note: "a fine morning we commenced wrighting &c." The Journals of Lewis and Clark August 30th 1803. [1] The Expedition's Route, August 30, 1803–August 24, 1804 (Journals 2, University of Nebraska Press, used with permission.) Left Pittsburgh [2] this day at 11 ock with a party of 11 hands 7 of which are soldiers, a pilot and three young men on trial they having proposed to go with me throughout the voyage. [3] Arrived at Bruno's Island [4] 3 miles below halted a few minutes. went on shore and being invited on by some of the gentlemen present to try my airgun [5] which I had purchased brought it on shore charged it and fired myself seven times fifty five yards with pretty good success; after which a Mr. Blaze Cenas [6] being unacquainted with the management of the gun suffered her to discharge herself accedentaly the ball passed through the hat of a woman about 40 yards distanc cuting her temple about the fourth of the diameter of the ball; shee fell instantly and the blood gusing from her temple we were all in the greatest consternation supposed she was dead by [but] in a minute she revived to our enespressable satisfaction, and by examination we found the wound by no means mortal or even dangerous; called the hands aboard and proceeded to a ripple of McKee's rock* [7] where we were obleged to get out all hands and lift the boat [8] over about thirty yards; the river is extreemly low; said to be more so than it has been known for four years; about [blank] we passed another ripple near [erasure] Past another bear or ripple with more dificulty than either of the others halted for the night much fatiegued after labouring with my men all day— [9] the water being sufficiently temperate was much in our favor; gave my men some whiskey and retired to rest at 8 OClock— 11th November— [1] Arrived as Massac [2] engaged George Drewyer [3] in the public service as an Indian Interpretter, contracted to pay him 25 dollards pr. month for his services.— Mr Swan [4] Assistant Millitary agent at that place advanced him thirty dollars on account of his pay.— January 1, 1804 [Clark] January 1st 1804 Snow about an inch deep Cloudy to day, a woman Come forward wishing to wash and doe Such things as may be necessary for the Detachmt Several men Come from the Countrey to See us & Shoot with the men, they bring Sugare &c. to trade, I purchase Sugar 6 lb at per pound, I put up a Dollar to be Shot for, the two best Shots to win Gibson best the Countrey people won ther dollar— (R [Reed?] & Ws. [Wiser, Windsor?] Drunk) a Perogue Passed Loaded with Salt & Dry goods. Jos: Vaun [1] offers to let the Contrator have Beef at 4$ pd. [pound or produce?] or 3$ 50 Cents in money, Pokers hake, the Nut is Sheshake, a plant growing in the ponds with a large broad leaf, stem in the middle of the leaf in french Volies [2] Three men Mr. Lisbet [3] Blacksmith &c, one Man offers to sell pork at [blank] apply to Hannerberry, [4] the blacksmith has traveled far to the north, & Visited the Mandols [Mandans] on Missouris, a quiet people 6 Day fr[om] [Ossini?] [5] or Red river & that the M: [Missouri River] is about 150 yds. over at this nation . Lewis and Clark http://geography.about.com/od/historyofgeography/a/louisianapurcha.htm Meriwether Lewis and William Clark led a government-sponsored expedition to explore the vast wilderness of the west soon after the signing of the Louisiana Purchase. The team, also known as the Corps of Discovery, left St. Louis, Missouri in 1804 and returned to the same spot in 1806. Traveling 8,000 miles (12,800 km), the expedition gathered huge amounts of information about the landscapes, flora (plants), fauna (animals), resources, and people (mostly Native Americans) it encountered across the vast territory of the Louisiana Purchase. The team first traveled northwest up the Missouri River, and traveled west from its end, all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Bison, grizzly bears, prairie dogs, bighorn sheep, and antelope were just a few of the animals that Lewis and Clark encountered. The pair even had a couple of birds named after them: Clark’s nutcracker and Lewis’s woodpecker. In total, the journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition described 180 plants and 125 animals that were unknown to scientists at the time. The expedition also led to the acquisition of the Oregon Territory, making the west further accessible to the pioneers coming from the east. Perhaps the biggest benefit to the trip, though, was that the United States government finally had a grasp on what exactly it had purchased. The Louisiana Purchase offered America what the Native Americans had known about for years: a variety of natural formations (waterfalls, mountains, plains, wetlands, among many others) covered by a wide array of wildlife and natural resources. Lewis and Clark Timeline http://www.nationalgeographic.com/lewisandclark/resources_timeline_1803.html January 18, 1803 U.S. President Thomas Jefferson sends a secret message to Congress asking for approval and funding of an expedition to explore the Western part of the continent. Spring 1803 Meriwether Lewis begins his training as the expedition's leader in Philadelphia. July 4, 1803 News of the Louisiana Purchase is announced; Lewis will now be exploring land largely owned by the United States. Summer 1803 In Pittsburgh, Lewis oversees construction of a keelboat, then picks up William Clark and other recruits as he travels down the Ohio River. Fall/Winter 1803 Lewis and Clark establish Camp Wood, the winter camp for their Corps of Discovery, on the Wood River in Illinois. Exploration: Lewis and Clark http://www.ushistory.org/us/21b.asp Originally named the Corps of Discovery, the 1803 expedition led by Lewis and Clark came in contact with people and places never before seen, and returned with stories that Americans in the East could hardly believe. On this map, the outbound leg of the expedition is red and the inbound route is blue. Even before Jefferson had completed the Louisiana Purchase, he had begun to make plans for a bold journey to explore the vast interior of North America that remained completely unknown to American citizens. That plan took on new importance once the United States had acquired the huge new territory from France. In May 1804, a group of 50 Americans led by MERIWETHER LEWIS, Jefferson's personal secretary, and WILLIAM CLARK, an army officer, headed northwest along the Missouri River from St. Louis. Their varied instructions reveal the multiple goals that Jefferson hoped the expedition could accomplish. While trying to find a route across the continent, they were also expected to make detailed observations of the natural resources and geography of the west. Furthermore, they were to establish good relations with native groups in an attempt to disrupt British dominance of the lucrative Indian fur trade of the continental interior. In mid-October, 1805 William Clark entered into his elkskin-bound diary — a map of the Columbia River. One of the purposes of the expedition, which was not realized, was to find a water route across the entire United States. By mid-October 1804, the LEWIS AND CLARK EXPEDITION reached the MANDAN villages on the banks of the upper Missouri River in present-day NORTH DAKOTA. Here they found several large, successful settlements with an overall population of about 5,000 people. The Mandan villages were an important trade center that brought together many different native groups as well as a handful of multilingual Frenchmen. The expedition chose to spend the winter in this attractive location and it proved to be a crucial decision for the success of their journey. During the winter they established good relations with the Mandans and received a great deal of information about the best route for heading west to the Pacific Ocean. The expedition also hired several of the Frenchmen who lived among the Mandans to serve as guides and translators. Along with them came a fifteen-year-old SHOSHONE named SACAJAWEA who was married to one of the Frenchmen. Her knowledge of the west and language skills played an important role in the success of the expedition. Additionally, the presence of Sacajawea and her baby helped assure other Indian groups encountered further west that this could not be a war party. From the Mandan villages the now enlarged expedition headed west to cross the Rockies, the highest mountain range in North America. By the winter of 1805 they had reached the Pacific Ocean via the COLUMBIA RIVER, becoming the first U.S. citizens to succeed in a trans-continental crossing north of Mexico. They were not, however, the first whites to accomplish this feat since ALEXANDER MACKENZIE had done so for a British-Canadian fur-trading company in 1793. Nevertheless, the Columbia River proved a much easier route than the one Mackenzie had taken a decade earlier. When the long overdue expedition finally returned to St. Louis in September 1806, they were celebrated as heroes who had accomplished an extraordinary feat. The expedition combined several qualities from scientific and military to trade and diplomatic, but the underlying motivation was prompted by Thomas Jefferson's widely shared belief that the future prosperity of the republic required the expansion of yeoman farmers in the west. This noble dream for what Jefferson called an "EMPIRE OF LIBERTY" also had harsh consequences. For instance, FORT CLARK was soon established at the Mandan villages. At first it provided the Mandans with a useful alternative to trading with the British and also offered military support from their traditional native enemies the Sioux. During his travels across the continent with William Clark and the Corps of Discovery, Meriwether Lewis fell 20 feet into a cavern, got poisoned and was shot in the thigh. In this engraving, An American having struck a Bear but not kill'd him escapes into a Tree, the American was none other than Meriwether Lewis. However, Americans at the fort unwittingly brought new diseases to the area that decimated the local native population. Where the Mandans had a thriving and sophisticated trading center when Lewis and Clark arrived in 1804, by the late 1830s their total population had been reduced to less than 150. The nation's growth combined tragedy and triumph at every turn. The Voyage of Discovery: Sacagawea http://nebraskastudies.org/0400/frameset_reset.html?http://nebraskastudies.org/0400/stories/0401_0107.html Imagine being a young teenage Indian girl married to a French Canadian over 40 years old who won you as a result of a bet with some Indians who, in turn, had captured you from your own tribe. Then imagine becoming pregnant and accompanying your husband and a band of, mainly, white men on an 8,000-mile expedition for 28 months into some of America's most treacherous territories. Such was the fate of Sacagawea, a member of the Shoshone tribe, who had been taken prisoner by members of the Hidatsa tribe. Her husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, was an independent trader who lived among the Hidatsas. Lewis and Clark accepted Charbonneau's offer to sign on as an interpreter, not so much because of his abilities, but because of his wife, Sacagawea. Sacagawea spoke Shoshone as well as Hidatsas, and a little French. Sacagawea played a very important role in the success of the expedition, not as a guide as she's been described, but rather as a person who could read the landscape fairly well. She could read the rivers the valleys. She had a sense of what the landscapes said about direction, where they were, and where they were going. She also had a sense of what could be eaten along the way as well as finding food. Her service as an interpreter proved invaluable when she negotiated with the Shoshone for horses. Without those horses, who knows what would have happened to the expedition. On August 17, 1806 as Lewis and Clark prepared to return to St. Louis and "settled up" with Charbonneau. He received approximately $500 for his horse, his tepee, and his services. Needless to say, Sacagawea received nothing. Unfortunately, there is a sad ending to the story of Sacagawea; although, there seem to be a variety of interpretations of what the final story was. One account indicates she eventually moves to St. Louis. Sacagawea was a citizen of the West, but someone who had citizenship no place else. Where did she belong — in a Hidatsa village, with her Shoshone relatives, in St. Louis? Where was her home? The last glimpses we have of her are in 1811 when a traveler described her as a woman wearing the cast off clothing of white women, drifting through St. Louis, seemingly alone, having given up her children to the care of William Clark. Regardless of the various accounts of what happened to Sacagawea after the expedition, it appears most are in agreement that she died in approximately 1812 when she would have been in her early twenties. If ever there was a displaced person, it was Sacagawea. An orphan in a world made by the expedition. Clark did pay tribute to Sacagawea in a letter to Charbonneau referring to her as, "Your woman who accompanied you that long dangerous and fatiguing rout to the Pacific Ocean and back disserved a greater reward for her attention and services on that route than we had in our power to offer her."