Water Quality 103: Hydromodification

advertisement

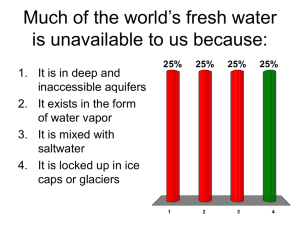

Water Quality 103: Hydromodification Bryan Duggan Water and Environmental Specialist If one was to compare aerial photographs of watersheds in human settled valleys as opposed to wilderness valleys, immediate differences in channel complexity would be noted. In a wilderness setting a river will often meander excessively if the landscape allows it, occupying multiply channels and connecting often with its floodplain through wetlands. An urbanized valley requires roads, culverts, dikes, canals, and even dams for human utilization; the river is often constrained and straightened as if its sole purpose was to drain the landscape as quickly as possible. These changes have a direct effect upon the hydrology of the valley and is often referred to as hydromodification. Hydromodification is the systematic response to alterations made by planned human interventions upon the hydrology of a given water body that changes the spatial and time patterns of the water body in such a way that complexity and ecosystem functionality is diminished. These anthropocentric changes upon the landscape are designed to improve drainage, store water, or even to improve access. The cumulative impact of these changes can drain wetlands, increase flood velocities, disrupt the water-sediment balance, and redirect surface and groundwater flows; which in turn could cause degradation of water resources. Since the dawn of recorded history, humans of all cultures have modified their environments to benefit human needs and values directly. This is nothing new, or deserving of a negative value judgment, but rather it is important for use to understand the impacts of such projects upon the hydrology and functionality of these water bodies in order to maintain ecological functionality. All natural water bodies provide some basic ecosystem services such as regulating water quality, providing wildlife habitat, recharging aquifers, and retaining stormwater runoff. Hydromodification can reduce the ability of a watershed to effectively provide these services. Immediate examples of hydromodification on Coquille Trust Lands include the small earthen dams on Fourth and Tarheel Creeks on the Empire Reservation. These dams serve to hold back and store water for use in fisheries, agricultural and recreational goals for the Tribe. The hydrology of the original streams has been altered to serve additional purposes other than habitat and watershed drainage; in turn the impacts of the stored water changes the flow patterns out into the bay, delaying seasonal freshets, altering groundwater levels and directly impacting physical water traits, such as temperature and dissolved oxygen levels within the aquatic environment. Such changes also have an indirect effect upon estuarine water quality and even the time and quality of salmon runs. On a riverine system, hydromodification includes multiple activities such as large wood removal, channelization of the river, fragmenting of reaches, and constraining river floodplains with roads and dikes. These changes reduce water holding times within the ecosystem and can contribute significantly to soil erosion. Roads located within river floodplains are often the most constraining of landscape modifications. Not only can they constrain a river to one channel which leads to an increase in discharge velocity and depth of that channel, roads also fragment river reaches, isolating wildlife populations from habitats necessary for life cycle stages. The channelization, or damming of a stream may be undertaken for several advantageous reasons. One is to make the river more navigable. Another may be to restrict the river in the bottom lands to make more lands available for agriculture. A third reason is for flood control, with the idea of giving the river as sufficiently large and deep a channel as possible to facilitate flood waters; all of which are reasonable and useful services. It is not necessary to dismantle our public works to restore stream functionality. There are advantages and disadvantages to river engineering and once we identify those influences we can address the losses through mitigation. Road culverts can be redesigned for fish passage, and where appropriate river channels can be released from their constraints to slow and retain flood waters, recharge ground waters and revitalize wetlands. Even low impact developments when designed intelligently can mimic the hydrological processes by infiltrating, retaining, and slowly releasing stormwater on a site by site basis. Instream restoration can add large wood in areas to restore complexity to the aquatic environment. This has the added benefit of creating fish and wildlife Habitat and retaining flood water sediments which can ultimately end up in our estuaries and cost a lot to dredge. Human development has brought many advantages to us economically and socially and has enabled us to farm once unavailable lands. Hydromodification can often be reduced with thoughtful planning and the use of low impact development designs, and where these changes can’t be avoided, additional solutions can be used, including instream restoration. When new development occurs at sites near streams that have already been degraded, more emphasis on stream restoration should be considered.