Pro Versus Anti Globalization Forces In OB Research And Applications

advertisement

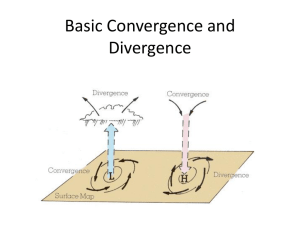

ISRAEL ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR CONFERENCE (IOBC) 2016 Symposium Proposal: Pro Versus Anti Globalization Forces In Ob Research And Applications Synopsis: Globalization is defined as the geographical dispersion of the business value chain, overlaid on increasing intra-regional and inter-regional flows of people, goods, companies, and ideas, and their respective interdependencies (Ronen &Shenkar, 2013). In recent decades, globalization has been on a steady march. The Globalization Index, by A.T. Kearney and Foreign Policy, shows rises on all indicators from economic integration (trade and foreign investment) to personal contact (travel and tourism), technological connectivity and political engagement (number of international treaties ratified). The popular viewof globalization, associated with Thomas Friedman’s popular bestseller The Word is Flat, which sees the world as populated byhomogenous actors, sharing values, attitudes and behavior, may be somewhat misleading. Research shows that it has not taken place, that not even ten percent of world’s population have fully “globalized” and that globalizationapplies only to the elites (Leung et al., 2005). Huntington (1993, 1997) hypothesizes that culture, not ideology or economics, will be the main fault line dividing humankind. The on-going debate is whether ConvergenceForcesor Divergence Forcesare dominating the globe. In this symposium, we will present research which support both views. Convergence Forces Convergence of national cultures is promoted by different forces, some historic, like colonization, and other more recent, like technology and communication. Political and trade blocs such as the EU, NAFTA and MERCOSUR have lowered the barriers to trade. People are constantly on the move, and thus exposed to different cultures and value systems (Gelfand et al., 2007:481). MNEs seek to transform themselves into ‘global organizations’, and strive to internationalize their board of directors and adopted “global management,” characterized by high mobility and cross-cultural teams, that would transcend national boundaries (Boeker, 1989; Brodbeck, 2000; Chatman &Jehn, 1994). As noted by Yip Document1 [Type text] 1 (1992), "Global organizationsmust now learn to integrate these diverse value systems to create their universal corporate culture”.The shift was consistent with the view of convergenceproponents, that cultural diversity is eroding (e.g., Cowen, 2002) or rapidly changing (e.g., Leung, Bhagat, Buchan, Erez, & Gibson, 2005), with some going as far as claiming that geographical distance is no longer a major factor in global business (Cairncross, 2001; Govindarajan& Gupta, 2001; Leung et al., 2005:359). Divergence Forces Contrary to that view, proponents of the divergence thesis hold that cultural variations are here to stay, because of how deeply rooted they, in part due to the fact that they have evolved to adapt to specific ecological conditions (Gelfand et al., 2011;Roos, Gelfand, Nau, &Lun, 2015). Some go further and argue that globalization mayreinforce cultural identities as those are threatened by incursion of foreign cultures (Huntington, 1997). Contrary to common assumption, enhancedcultural interaction may actually intensify cultural consciousness as awareness of differences triggers animosities and reinforces one’s own culture(Huntington, 1993, 1997; Leung et al., 2005).Examples include the disintegration of multicultural national entities (e.g., Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia) and the establishment of new nations (e.g., Kosovo) along cultural and ethnic lines.Today, Europecomprises some 40 countries with 45 official languages and multiple diversity factors (Diamond, 2005). Ronen &Shenkar (2013) updated cultural map shows that little has changed from the previous clustering solution that was generated in 1985, and that the same cultures continue to cluster together, and the GLOBE research project also showed strong correlations between cultural values and practices in their study with that of Hofstede (1980). In order to overcome the continued debate between convergence and divergence, Ronen offers a hybrid scenario aptly described as “semiglobalization” or an “intermediate degree of globalization”. Forces such as computer-mediated communication may be powerful, but they have the potential to increase both cultural convergence and divergence (Leung et al., 2005:360); technology in general has the power not only to converge but also to sustain cultural divergence (Hofstede, 2001; Leung, et al., 2005). Various studies find evidence for both continuity and change (Inglehart& Baker; 2000; Leung, 2005). Leung et al. (2005) observe that whereas Document1 [Type text] 2 consumer values and lifestyles show signs of convergence, significant cultural divergence persists. Even where economic development is concerned, countryspecific modes are likely to produce cultural variants (Leung et al., 2005). Institutions have their own traditions and cultures, which mediate outside influences (Bamber& Lansbury, 1998), and their endurance provides a foundation for cultural stability; this produces variable impact for individualism, long-term orientation, and power distance on the one hand, and uncertainty avoidance and masculinity on the other, since the latter reflects stable institutional traditions, such as language, religion and climate, that are less likely to change over time (Tang &Koveos, 2008). As Smith et al. (1997) note, the adoptionof some shared values does not indicate that world is converging, as it is possible that those values will evolve via interaction with other cultural values as well as with institutional and other host country variables. Exposure to other cultures is unavoidable, the authors acknowledge, but the curiosity and fascination associate with, sayconsuming ethnic foods, should not be confusedwith adopting the set of values, or, in particular workrelated values, associated with that ethnicity. But which values will change? Will they be those that are least important? This too is impacted by culture: As Triandis (1989) put it, having reviewed 100 comparative studies of values: "the values that are most important in the West are least important worldwide" (Huntington 1993:41?). The findings above suggest the possibility of “crossvergence”, a meeting of convergence and divergence that will drive unique value systems as well as commonalities (Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung, &Terpstra, 1993; Ralston et al., 2008). Crossvergence proponents see integration of cultural and ideological influences that will result in a value system that borrows from as much from national culture as it does from economic ideology (Ralston et al., 2008). But is crossvergence itself a transitional state on the way to convergence? Simply put, we do not know. What we do know is that even if convergence forces are sustainable, their impact will take a long time and may be superficial, having but a minor impact on fundamental issues such as beliefs, norms, and ideas (Leunget al., 2005:359). Or, it can have divergent outcomes for different level of cultural entities. Child (1981) observed that studies showing convergence tend to include macro level variables, such as structure and technology, while divergence studies target micro level variables, such as the Document1 [Type text] 3 behavior of people in organizations (Child, 1981), with the latter more resistant to change because of their embedment in deep seated beliefs. One semi-globalization force is immigration. Ethnic groups, many retaining their home languages, now make up over half of the US population, and most European nations are now way less homogenous than just a few decades ago. The melting pot has been replaced with a mosaic, where immigrants retain much of their former culture or develop bicultural identity (Ryder, Alden, &Paulhus, 2000; Van de Vijver&Phalet (2004).This has rendered the old one-dimensional models, which were based on the perception that as individuals spend more time in a second culture,they simultaneously must become more oriented toward that culture and relinquish their heritage culture, at least partly obsolete (e.g., Cuellar, Harris, & Jasso, 1980; Suinn, Rickard-Figueroa, Lew, & Vigil, 1987; Huynh et al., 2009: 256-257). It was replaced, or at least supplemented by a bidimensional (bilinear) acculturation model that proposes individuals may have independent orientations toward their heritage culture and the host or dominant culture, i.e., independent cultural orientations (Berry, 2003; Cuellar, Arnold, and Maldonado, 1995; Ryder, Alden, &Paulhaus, 2000; Stephenson, 2000; Tsai, Ying, & Lee, 2000). Semi-globalization is also likely to vary based on the level and scope of involvement with international activities and exposure to global forces. For instance, Hewitt (2009) distinguishes between multinational (have crossborder operations that are primarily decentralized and autonomous, international (have a headquarters that retain some decision-making control but the organization is still largely decentralized), transitioning to global (taking steps to form worldwide strategies and policies and truly global (develop strategies and policies on a worldwide basis and share resources across borders). This implies a higher probability for adopting ‘universal’ values for the more global firms. Document1 [Type text] 4 Author 1 will discuss ambiculturalism. He will expand on the theme of East meets West in the widening the context of 'Eastern' and 'Western' philosophies beyond China and North America. In addition, Ashkanasy will present his fusion theory (2012) to strengthen this new direction of research by expanding its geographical and organizational focus. Author 2 will discuss and present research on the dual – global identity and local identity, which demonstrates that individuals who are exposed to the global context, develop multiple identities that enable them to feel a sense of belongingness to the culturally diverse global social group and at the same time maintain their own local cultural identity. This dual identity enables them to adjust to both cultural contexts. In that respect, her research supports the “crossvergence” approach, which advocates “both” instead of “either”/ “or”. Author 3 will discuss the critical role that psychological theory plays in understanding reactions to globalization, and in turn, how globalization research provides a new context that challenges, refines, and extends psychological theory. She will offer suggestions as to how psychology can take an active role in the future of globalization research, in particular in specifying the psychological dimensions on which globalization is construed (e.g., morality, power) and the implications these construals have for reactions to globalization. In addition, Gelfand will discuss the convergence and divergence perspective with respect to the strength of social norms or tightness-looseness. Author 4 will present the updated synthesized cultural clustering ofcountries based on similarity and dissimilarity in work related attitudes (Ronen &Shenkar, 2013). The new map uses an updated dataset and expands coverage to world areas that were nonaccessible at the time. Cluster boundaries are empirically rather than intuitively drawn, and the plot obtained is triple-nested, indicating three levels of similarity across given country pairs. Also delineated are cluster adjacency and cluster cohesiveness, which varies from the highly cohesive Arab and Anglo clusters to the least cohesive Confucian and Far Eastern clusters. In addition, the new map will be compared with that of 1985, to show strong support for the divergence (vs. convergence) argument. Implications for OB research and managerial practices are delineated. Document1 [Type text] 5