Prolonged Pyrexia - edited - Ankur Institute of Child Health

advertisement

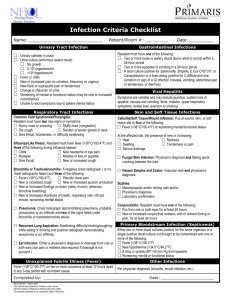

Prolonged Pyrexia: Dr Raju C Shah, MD, Dped, FIAP Prolonged Pyrexia (Fever) of unknown origin (PUO/FUO) has been described using several definitions. In 1961 Petersdorf and Beeson defined FUO in adults as fever, documented temperature above 101° F on several occasions, persisting for more than 3 weeks and an uncertain diagnosis after extensive evaluation in the hospital for 1 week.[1] These definitions, although still employed, may not be very useful for pediatric patients in today's clinical environment. Many diagnostic tests were not available when the FUO definitions were made .This increased armamentarium of diagnostic tests has changed the approach to patients with prolonged fevers. Indeed, many cases defined as FUO in the past are now diagnosed early in the course of illness. Fever of more than 2 weeks duration is considered prolonged pyrexia undiagnosed after extensive investigations. The biggest concern in evaluating FUO is identifying patients whose fever has a serious or lifethreatening cause in which diagnostic delay could lead to a poor outcome. In a comprehensive overview of fever in pediatric patients Kathryn Edwards[2] pointed out that the initial approach to any patient with history of prolonged fever is to document its presence and the pattern(s) of presentation. Most research conducted with children has identified infectious diseases as the most common cause of FUO, with anywhere between 30% and 70% of cases explained by infection. [3, 4] Obtaining a comprehensive exposure and travel history is essential for establishing a working differential diagnosis. Many diseases are endemic to certain regions of the world (i.e., typhoid fever, tuberculosis, malaria) or to certain countries (i.e., ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease, blastomycosis, tularemia, and histoplasmosis).[3, 4] Exposure to pets or wild animals may also give a clue to the diagnosis (i.e., cat-scratch disease, brucellosis, leptospirosis, salmonellosis, tularemia, visceral larva migrans, and toxoplasmosis) [3] In addition attention to localized infection as the cause of FUO is also helpful. Urinary tract infections, sinusitis, mastoiditis, or central nervous system infections are some common diseases presenting as FUO.[3, 4] Clinicians must remember that PUO is more likely to be uncommon presentation of common disease rather than an uncommon disease. In most of cases diagnostic difficulties posed by inappropriately treated pyrexias and most errors in diagnosis can be due to cursory incomplete examination than due to lack of knowledge & skills. When one examines any child with prolonged pyrexia it is very important to look for red flag if any like • Fever lasting over 4 wks • Bone pains, adenopathy, patechie and ecchymoses • Persistent thrombocytosis, elevated PMC, leucopenia, pancytopenia, dropping HB • Mouth ulcers, hair fall, extreme weakness • Features of Kawasaki Disease If yes – hospitalize at a higher center for investigations and management. History is very useful in any case of prolonged pyrexia. The following questions might be helpful: What is the timing of the current illness? When did the fever start? How long has the fever been present? Are there any related symptoms? What is the patient's medical history? The history may not be applicable in all cases, but it must be explored to reveal potential high risk or complicating factors. Has the child's activity significantly changed during the illness? Is the child tolerating fluids at home? Has the child been less interested in eating? Have the stool patterns changed in consistency or frequency? Has there been recent antibiotic use? Has there been exposure to illness through babysitters, day care contacts, or other caregivers? Are others at home sick? Have the sleep patterns changed? Has the patient been snoring more at night than usual? Has there been any recent travel that might have exposed the child to illnesses? Clinical Pearl: The clinician should be aware that even the most thorough evaluation can fail to reveal the underlying cause of FUO. If no cause can be determined, repeated physical examinations and patience are then the best approach. The three most common etiological categories of FUO in children in order of frequency are infectious diseases, connective tissue diseases, and neoplasm. In addition, there are causes of FUO, such as drug fever, factitious fever, central nervous system dysfunction, and others, that do not fit into the above categories. In a few cases, there may be a very slow progression to obvious clinical manifestations of rheumatic disease or chronic inflammatory disorder. Commonest causes of fever are – Typhoid, Respiratory infections, Tuberculosis, UTI, Deep seated abscesses, Extended viral infections, Osteomyelitis, Brucellosis, endocarditis, Connective tissue inflammation and malignancies esp. related to blood and lymphnodes. However, in the majority of patients, fever will eventually resolve without any specific cause ever being delineated [5, 6]. Some of the periodic fever may also need to be ruled out. The most important periodic fever syndromes identified are PFAPA (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis) syndrome, familial Mediterranean fever, hyper-IgD syndrome (HIDS), and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (familial Hibernian syndrome). In many cases, a definitive diagnosis is never established and fever resolves. Clinical Pearl: Assiduous examination of ears, nose, throat, sinuses & chest very important as more than 50% cases are having Respiratory cause. Clues to FUO Cause To help narrow down what is causing fever in the child, following questions can help: Has he been around anyone else that has been sick? Has he traveled out of the country recently? (Malaria) Has he been around any farm animals or wild animals? (Brucellosis, Tularemia) Do you have any pets? (reptiles - Salmonella infections, Birds - Psittacosis) Has he been bitten by a tick? (Lyme Disease, Q Fever, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever) Has he been scratched by a kitten? (cat-scratch disease) Has he eaten any raw or undercooked foods or drink unpasteurized milk or juice? Does he have a heart murmur? (bacterial endocarditis) Has he been taking any medications? (drug fever) Does anything like this run in the family? (familial Mediterranean fever) In addition to the fever, has he had other symptoms, like night sweats and weight loss? (lymphoma) Clinical Pearls: • In most of cases diagnostic difficulties posed by inappropriately treated pyrexias • Most errors in diagnosis due to cursory, incomplete examination than due to lack of knowledge & skills In all cases of prolonged pyrexia following algorithmic approach can make the task easier. Algorithm for Prolonged Pyrexia Fever of more than 15 days Proven Etiology or Site of Infection identified No diagnosis / No response to empirical therapy Review basis of Diagnosis Definitive Presumptive Consider Resistant Infection Attempt definitive diagnosis with appropriate serology, histology, microbiology Change / Add Antibiotic Change / add antibiotic Consider complications of disease Or Immunodeficiency Search for associated complications Drain pus, hematoma, if identified Remove shunts, prostheses, etc. Consider resistance only if microbial diagnosis available or only as a last option Rule out immunodeficiency Review Symptoms, Physical signs and Investigations at every stage & Reconsider Diagnosis Consider second pathology only as last option - Review symptoms, signs and investigations - Perform additional relevant investigations Definitive/ Presumptive Institute appropriate treatment Continue to observe/investigate No definitive diagnosis Next page.. Algorithm for Prolonged Pyrexia (page 2) No definitive diagnosis Child toxic, sick, unstable, High risk group Yes Specific therapy, If not possible – use broad-spectrum antibiotic combination Continue to observe/investigate No Stop antibiotics Observe Reinvestigate Review Symptoms, Physical signs and Investigations at every stage & Reconsider Diagnosis Consider second pathology only as last option References: 1. Miller L, Sisson B, Tucker L, Schaller J. Prolonged fevers of unknown origin in children: Patterns of presentation and outcome. J Pediatr. 1996; 12:419-423. 2. Edwards K. Fever: From FUO to PFAPA to recurrent or persistent. Program and abstracts from the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference and Exhibition; October 9-13, 2004; San Francisco, California. Session S375. 3. Campbell J. Fever of unknown origin in a previously healthy child. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2002;13:64-66. 4. Miller M, Szer I, Yogev R, Bernstein B. Fever of unknown origin. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1995;42:999-1015. 5. Steele R. Fever of unknown origin. A time for patience with your patients. Clin Pediatr. 2000;39:719-720. 6. Alpern ER, Henretig FM. Fever. Fleisher GR, Ludwg S, Henretig FM, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:295-306.