Artificial

advertisement

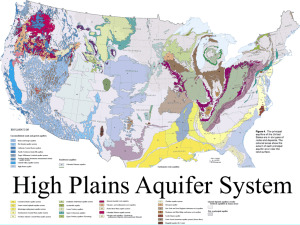

Aquifer Recharge projects catching on in water-strapped cities The Ogallala Aquifer occupies the High Plains of the United States, extending northward from western Texas to South Dakota and is the major aquifer for Howard & Martin Counties. The Ogallala was created 10 million years ago by fluvial deposition from streams that flowed eastward from the Rocky Mountains during the Pliocene epoch. Erosion has removed the deposits between the mountains and the existing western boundary of the Ogallala, so there is no longer water recharge being received from the Rockies. Natural recharge to the Ogallala aquifer occurs primarily from rain, snowmelt, river and reservoir leakage, or from irrigation. It is recognized that playa lakes are the primary points of most natural recharge. Recent studies have estimated an average recharge rate for the entire High Plains region of approximately 0.5 of an inch per year. The amount of water in storage in an aquifer is reflected in the elevation of its water table. If the rate of recharge is less than the natural discharge rate, the water table will decline and the aquifer's storage will decrease. The use of artificial recharge to store surplus surface water underground can be expected to increase as growing populations demand more water. Artificial Storage and Recovery (ASR) programs are being implemented as a way to store water in aquifers during times when water is available and recover the water when it is needed. The State of Texas has seen ASR programs implemented in such places as the San Antonio Water System (SAWS). The Corpus Christi Aquifer Storage and Recovery Conservation District is in the preliminary testing stage for the ASR program. As the artificial aquifer recharge gains momentum state wide it is also becoming of interest nationally. Utilities and water managers from Florida to California are beginning to rely on recharged aquifers to help maintain water supplies during periods of drought. For instance, Florida aquifers are routinely recharged in the winter, and then tapped in the summer when water demand exceeds supply. In other areas, geologic constraints and the need for long-term storage have led water managers to view aquifer recharges and withdrawals as a last resort. In Albuquerque, water officials hope the Bear Canyon pilot project will demonstrate that infiltrated water from the Rio Grande can recharge the over pumped Middle Rio Grande Basin aquifer and effectively store water for use in times of drought. Stephanie Moore, manager of the project, noted that cities typically store water in reservoirs, but in dry states like New Mexico, 10 to 15 percent of that water is lost to evaporation. Storing some of the water underground reduces that loss to about 3 percent, and shields it from the vagaries of the elements. Researchers continue to work on methods to increase natural recharge to the aquifer and to improve water-use efficiency. The prospects for the future of the Ogallala aquifer ultimately depend upon its management by each of its water users. The Permian Basin Underground Water Conservation District invites you to view their website at www.pbuwcd.com for more information on Recharge Enhancement. You can also call their office at 432-756-2136 or email us at permianbasin@sbcglobal.net.