English PG Handbook 2015-16

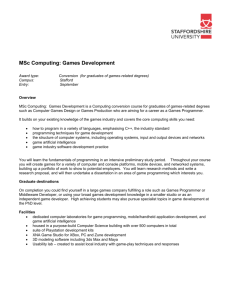

advertisement