Unit 2 - Ram Pages

advertisement

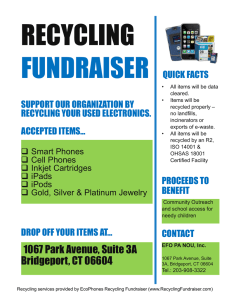

Hall 1 Lindsay Hall Professor Elise Glaum UNIV 111 November 4th, 2014 The Cycle in Recycle As I began watching the environmental documentary Bag It, my ears filled with oddly upbeat music and the voice of your average man—no Morgan Freeman-type tone—who had decided to look into the world’s obsession with plastic. Shopping bags caught in tree limbs, water bottles littering the streets, and plastic packaging floating in the ocean dominated the screen in front of me. It’s alarming how accustomed I have come to these images. Yes, of course they are still frightening, but I see that sort of thing everyday walking around outside—actually even inside. Just under my desk in my dorm is a plastic bag filled with plastic bags that are just sitting there. I’ve accumulated them over the past few months with trips to Kroger and Rite Aid and the various food choices on campus that insist on giving a complementary plastic bag with every meal. It has all become commonplace. What harm could they be, really? They have that familiar chasing arrow on them to indicate that they’re recyclable, so what’s so bad? My mind thought back to the trash room in GRC. The metal door opens to a room flooded with dim, yellow light in which two metal dumpsters reside. One is for trash and the other is designated for recyclables. It’s simple to tell which is which due to the superfluous amount of stickers indicating what you can and cannot put inside of it. There are three separate stickers that state specifically that you cannot put plastic bags in the recycling bin. How can that be? How can plastic bags not be put in the same recycling as plastic packaging? Hell—how can plastic bags not be put in the same Hall 2 recycling with every other recyclable out there—glass, plastic, paper, and cardboard? My ignorance hit me. How is that type of recycling even possible? What happened to separating papers from plastics? The ultimate question eating at me was something I felt I should already know the answer to: How does single-stream recycling work after it leaves our curbsides? As the documentary played on, it continually pushed the naivety of society, and I watched with fists clenched around my pillow, finding it hard to come to terms with. For something that is clearly such a large part of everyday life, it is crazy that a great deal of the population is clueless to the lifecycle of recyclables once they are out of their sight. I find it difficult to understand how we continue to function as such a clueless society. Of course, the type of recycling you have is all dependent on what area you live in. Some areas isolate their recycling with paper, plastics, and glass. Other areas simply throw all of the recyclables into one bin and call it a day. Once that recycling bin leaves the curb, we forget about those bottles and boxes and carry on with our lives, continuing to obtain and dispose of what seems like an endless supply of plastic. Just because people might be guilty of not knowing the whole recycling process does not necessarily mean they do not care, but rather they are just uninformed and undereducated on the process. According to Sarah Laskow, a writer for the Atlantic with a Bachelors degree in Literature from Yale University, the system of single-stream recycling first emerged in 1990s California, and it has only grown from there. This simpler process arose for two main reasons: 1) it is less of a hassle so more people tend to participate, and 2) it is only one pile for the collection truck to deal with which saves cities money (Laskow). The real action takes place once it reaches the material recovery facility, or MRF for short. These buildings act as the middlemen between recycling collection and the markets that use the materials to make new products. The MRFs that Hall 3 deal with single-stream recycling are referred to as “dirty” material recovery facilities due to the high level of work it takes to sort out the different objects. Salman Zafar, a celebrated expert in the fields of waste management and sustainability with a Masters degree in Chemical Engineering, states that these facilities use a combination of machinery, such as magnets, and manpower to complete the laborious separating of materials (Zafar). Due to the high-level of effort required to run such facilities, the process of single-stream recycling actually ends up being “more expensive than sorting things before they got to the dump” (Laskow). Essentially, the process was created to make things simpler and cheaper, but in reality it’s been making things more complicated and costly. Another problem that dirty MRFs face is the risk of cross-contamination between materials. The material that tends to be the biggest hassle is the glass. Through all the sorting, dumping, and crushing, the glass ends up broken and shattered and ultimately compromises the integrity of the other bales. Since it is sometimes difficult to ensure that the bales are purely one material, many recyclables end up in landfills as if the items had just been thrown out in the first place (Laskow). Items that end up in landfills pile up to essentially be mummified, and although they are carefully engineered, “they can leak liquids into the ground water” (Krusinski). So while many people intend to do good by recycling, it’s actually extremely complicated and isn’t a flawless method. MRFs have definite upsides too though. Many materials are recycled on again, like glass and aluminum, and some materials are put to use as fuel source to produce energy (Zafar). According to Dan Kulpinski, who has a Masters degree in Environmental Sciences and Policy, explains that the items that are recycled into new goods, an enormous amount of energy is saved. For example, to create an aluminum can from recycled materials “takes 95 percent less Hall 4 energy…than from virgin bauxite ore” (Kulpinski). The recyclables that do end up being processed and reused make a huge difference to the overall materials consumed and energy used to salvage raw resources. Overall, single-stream recycling is a convenience. Sorting out paper from plastic from glass seems like such a trivial thing to be annoyed about, but we would rather throw it all in one bin and leave it for someone else to figure out. We are so accustomed to convenience. That’s why plastic is so great to begin with—it’s disposable. Why bother doing the dishes when you can just throw them away? Or, recycle them rather. Recycling is the crutch that people use to fall back on to justify why their plastic consumption is acceptable, but the whole process just “lulls people into thinking they are making a difference” (Bag It). Hall Works Cited Bag It. Dir. Suzan Beraza. Narr. Jeb Berrier. Reel Thing, 2010. Film. Kulpinski, Dan. “Human Footprint: Where Does All the Stuff Go?” National Geographic. National Geographic Society, 2014. Web. 1 Nov. 2014. Laskow, Sarah. “Single-Stream Recycling Is Easier for Consumers, but Is It Better?” theatlantic.com. The Atlantic Monthly Group, 18 Sept. 2014. Web. 26 Oct. 2014. Zafar, Salman. “Introduction to MRF.” EcoMENA. EcoMENA, 18 Feb. 2013. Web. 27 Oct. 2014. 5

![School [recycling, compost, or waste reduction] case study](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005898792_1-08f8f34cac7a57869e865e0c3646f10a-300x300.png)