(2014) Terrorism, Discourse and Analysis Thereof

advertisement

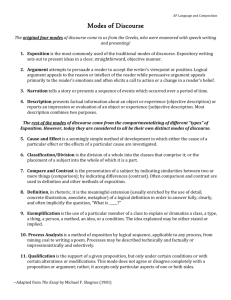

Terrorism, Discourse and Analysis Thereof: A Reply to Clément Lee Jarvis This is the submitted, pre-print version of a paper subsequently accepted for publication and forthcoming in Global Discourse: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Current Affairs and Applied Contemporary Thought. The accepted version of the paper can be found online here: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23269995.2014.930599?journalCode=rgld20#. U7M0BfldWV0 DOI: 10.1080/23269995.2014.930599 Terrorism, Discourse and Analysis Thereof: A Reply to Clément Lee Jarvis1 School of Political, Social and International Studies, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Norwich Research Park, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, NR4 7TJ Clément’s discussion of Al-Muhajiroun (AM) presents, in my view, an important contribution to discursive studies of ‘terrorism’ and ‘counterterrorism’ on two principal grounds. In the first instance, it focuses on the written and spoken language of a relatively under-explored group, which had been extremely visible within UK politics until its proscription in 2010. Most significant here - as Clément demonstrates - is that AM’s language departed quite markedly from that of more intensively analysed organisations, not least in its initial ambiguity toward the meaning of the 9/11 attacks and the lessons thereof. In this sense, Clément usefully broadens our understanding of the different ways in which groups that might be deemed ‘terrorist’ legitimise their campaigns, and of the significance of changes therein. The second reason that this article merits wide reading is the use to which recognition theory is put in its attempt to explore transformations in AM’s articulation of its own struggle. Of particular interest here is the turn toward self- and divine- recognition as sources for self-validation; a turn that was made necessary, for Clément, following the denial of the ‘West’s’ status as a significant other with whom recognition might be negotiated. In making these contributions, Clément’s analysis speaks to (yet does not directly address) contemporary developments within what some have termed ‘critical terrorism studies’ (e.g. Jackson et al 2009, Jackson et al 2011). Although heterogeneous, contributions to this ‘project’ - if it may be described thus - share Clément’s desire to engage with, destabilise and deconstruct representations of (counter-)terrorist violence. In the process, they pull attention to the constitutive and performative functions of such representations, and their role in the continuous (re)making of social worlds. Where recent work in this area goes beyond Clément’s, however, is by demonstrating that categories such as ‘radicalisation’ must also be approached as discursive productions rather than given the taken-for-granted status they are afforded in this discussion (e.g. Baker-Beall et al forthcoming). Thus, whilst Clément takes the growing radicalisation of AM as her object of analysis - as something to be explained (here, through recognition theory and discourse analysis) - it might be more useful, I think, to begin our analysis with the ways in which AM is itself discursively constructed as a radicalising entity by legislators, academics and other interested parties. As Heath-Kelly (2013) argues (focusing - as does Clément - on the UK context), ‘radicalisation’ has a particular history and an important role in contemporary security politics, each of which should be acknowledge in the discussion and analysis of groups such as AM before they are described thus. 1 Email: l.jarvis@uea.ac.uk This brings me to my second point, which is Clément’s treatment of discourse more generally. Although not fully elaborated, Clément makes a distinction, following Neumann, between two types of discourse analysis. These might be thought of as forward and backward looking variants which seek either to explore the range of possible outcomes from discursive acts, or, alternatively, to begin with such outcomes and investigate their (prior) conditions of possibility within the realm of representation. While potentially useful, discourse here is treated with a thinness which implies that there exists something beyond or beneath it. This comes through in the article’s empirical analysis in which AM’s struggle for recognition is connected to, but seemingly distinct from, the articulation of events and identities. In other words, a desire for recognition is depicted here that exceeds the relational construction of identity to which Clément points: a desire that may be satisfied or frustrated given how discursive developments play out. Whether we agree with Clément’s ontology or not, her approach to discourse is one in which it is possible to say something about the ‘truth’ of particular social meanings away from their content. It is possible, put otherwise, to engage in explanatory analysis of this group’s discursive practices and the consequences thereof because of the importance of recognition within social interaction. This example of what we might call ‘discursive discovery’ may be contrasted with two alternative approaches to discourse analysis (see Howarth 2000: 128-130; Jarvis 2009). The first, ‘discursive recovery’, involves reconstructing the purposes or intentions behind discursive acts. This would involve, in this example, asking why AM sought to construct its struggle as it did, and searching for intentionality within this construction. The second, termed here ‘discursive invention’ (see Caputo 1997), approaches the meaning of discourse instead as something which is invented in the context-bound, active negotiation that takes place between discourse and analyst. This type of study would likely focus on destabilising and deconstructing AM’s struggle - in its own terms - rather than seeking to explain this via the extra-discursive role of affective factors such as recognition. And, in so doing, it would recognise that any destabilisation was a product of the inventive reading of the analyst herself. In this sense, it might be more useful, I suggest, to substitute Clément’s two approaches to discourse analysis with three that are organised around an epistemological rather than temporal division. References Baker-Beall, C., Heath-Kelly, C. and Jarvis, L. eds. Forthcoming. Counter-Radicalisation: Critical Perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge. Caputo, J. 1997. Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida. New York, NY: Fordham University Press. Heath-Kelly, C. 2013. “Counter-Terrorism and the Counterfactual: Producing the ‘Radicalisation’ Discourse and the UK PREVENT Strategy.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 15(3): 394-415. Howarth, D. 2000. Discourse. Buckingham: Open University Press. Jackson, R., Breen Smyth, M. and Gunning, J. eds. 2009. Critical Terrorism Studies: A New Research Agenda. Abingdon: Routledge. Jackson, R., Jarvis, L., Gunning, J. and Breen Smyth, M. 2011. Terrorism: A Critical Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave. Jarvis, L. 2009. Times of Terror: Discourse, Temporality and the War on Terror. Basingstoke: Palgrave.