ANTIQUITY TO 1590 Copyright 1999, John Koopman. Conservatory

advertisement

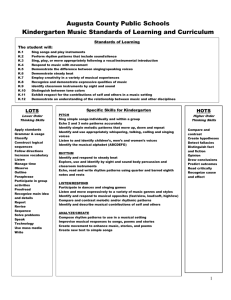

ANTIQUITY TO 1590 Copyright 1999, John Koopman. Conservatory of Music, Lawrence University, Appleton, WI PREHISTORIC VOCALISM In the beginning was the voice. Voice is sounding breath, the audible sign of life. --Ibid. Men sang out their feelings long before they were able to speak their thoughts. But of course we must not imagine that "singing" means exactly the same thing here as in a modern concert hall. When we say that speech originated in song, what we mean is merely that our comparatively monotonous spoken language and our highly developed vocal music are differentiations of primitive utterances, which had more in them of the latter than of the former. These utterances were, at first, like the singing of birds and the roaring of many animals and the crooning of babies, exclamative, not communicative--that is, they came forth from an inner craving of the individual without any thought of any fellowcreatures. Our remote ancestors had not the slightest notion that such a thing as communicating ideas and feelings to someone else was possible. --Otto Jespersen, Language, Its Nature, Development and Origin Singing, the vocal production of musical tones, is so basic to man its origins are long lost in antiquity and predate the development of spoken language. The voice is presumed to be the original musical instrument, and there is no human culture, no matter how remote or isolated, that does not sing. Not only is singing ancient and universal, in primitive cultures it is an important function associated not so much with entertainment or frivolity as with matters vital to the individual, social group, or religion. Primitive man sings to invoke his gods with prayers and incantations, celebrate his rites of passage with chants and songs, and recount his history and heroics with ballads and epics. There are even cultures that regard singing as such an awesome act they have creation myths relating that they were sung into existence. It is likely the earliest singing was individualistic and improvisatory, a simple imitation of the sounds heard in nature. At what point the singing of meaningful, communicative sounds began cannot be established, but it was doubtless an important step in the creation of language. Many anthropologists believe the development of a lowered larynx (important to articulate speech, as it effectively makes the flexible lower tongue the front wall of the pharynx) was a relatively recent aspect of human evolution. There are no bones in the human larynx, so archaeological remains offer no direct physical evidence of the vocal apparatus of prehistoric man. We lack studies that correlate vocal characteristics to body size, the basic gender difference aside, but there is general belief large-bodied peoples (Slavs, for example) frequently produce low-voiced singers, while small-bodied peoples (Mediterraneans, for example) produce more high-voiced singers. If there is any validity in this, the voice that belonged to the owner of the prehistoric jaw bone unearthed in 1909, at Heidelberg, Germany, may have been remarkable--it is half-again the size of a modern jaw. Carrying the idea of relating body size to vocalism into more recent periods, we see modern man has grown too large to fit the armor of medieval knights and, still more recently, we suspect an increasing rarity of the male alto voice type. Tempting though it is to see a relationship between such things, we lack the means to support it factually. Based on our knowledge of the singing of present-day primitive peoples, a possible scenario of musical development would begin with simple melodic patterns based on several tones. Pitch matching (several persons singing in unison) might emerge next, with singing in parallel motion (the natural result of women or children singing with men), call-and-answer phrases, drone basses and canon as subsequent steps. All this could lead to an evolving sense of tonic and scale structure (primitive music often uses pentatonic scales) and the development of such basic musical devices as melodic sequences and cadential formulae. HISTORICAL ANTIQUITY The major early cultures that were sources for Western music each had distinguishing musical characteristics that related, in some degree, to their respective languages. Experts recognize that a culture's spoken language and its musical expression influence each other, but the relationship is very complex and not well understood. That modern French woodwind players produce a distinctive timbre, that 6/8 metrics are nonexistent in Hungarian folksong, and that Western classical vocal technique developed in an Italian-speaking region are examples of the relationship. It is not known when or where art music--as distinct from folk music--began, but there is evidence the various Mesopotamian cultures that thrived from 3500 to 500 B.C. already considered music an art, and their writings mention both professional musicians and liturgical music. It is a song, the Sumerian Hymn to Creation, dated before 800 B.C., which is the oldest notated music extant. Egyptian musical culture existed by the 4th millennium B.C., and music was prominent in the social and religious life of the Old Kingdom. Egyptian instruments changed significantly as the New Kingdom era (1700-1500 B.C.) began. The change, which may have reflected foreign influence, was from delicate timbre instruments to louder ones and was surely followed by similar changes in singing tone for, over time, a culture's instrumental timbres and vocal tone always tend to match. There are many drawings extant showing that large choruses and orchestras existed in the New Kingdom. Grecian culture had a highly developed art music that showed signs of both a folk music origin and some Egyptian influence. The poetry of Sappho (600 B.C.) and others was often sung in contests, with melodies and rhythms based on the poetic meters. Singing was associated with all forms of literature and with dance. The ode, the dithyramb (a choral tribute to Bacchus and the forerunner of tragedy), and the drama all employed singers who moved to the rhythm of the music. By 500 B.C. ventriloquism had been described, and both choruses and solo voices were being used in drama. Greek philosophers attached great value to music and to its cultural purposes. The PYTHAGOREAN SCALE (see Glossary) and a complex theory of music were developed. The Judaic culture has preserved some melodies that may go back to 500 B.C. The Psalms of David and the Song of Solomon were sung, and we know of an early presence of professional musicians. Both responsorial (a soloist answered by the congregation) and antiphonal (alternating congregational groups) styles were used in singing the Psalms. After the destruction of the Second Temple, in 70 A.D., Jewish music became exclusively vocal. As the dispersed and transient Jews would learn, the human voice is a readily portable instrument, and communal singing serves to bond its participants in both form and purpose. Like the Egyptians, Jewish singers may have shared musical directions and reminders with hand-signs (CHEIRONOMY). Cantillation, the intoning of sacred texts using ancient melodic formulae, written with symbols called ta'amim, was an important musical format. Jewish prayer chants, which were based on ancient melodic lines and often highly ornamented, would have a considerable influence on Christian plainchant. What little we know of Roman music shows it to have been derived from the Greeks but primarily instrumental and military in nature. Still, Seneca (4 B.C.-64 A.D.) wrote of being disturbed late one night by loud sounds coming from a group of singers practicing vocal exercises. Singing was such an important part of early Christian worship that its ritual and music developed together and became almost inseparable. It borrowed music from other religions and from existing secular tunes and slowly developed a form of liturgical chant. It was a style based on sinuous melodies of limited range, expressed in free, unmetered rhythms. These were sung as solos or in unison by unaccompanied male voices. The various scale formats in which they developed were eventually refined into a complex theoretical system of so-called church modes. As the Christian church became organized it tried to suppress secularism and secular singing while advancing both itself and its chosen musical style--plainchant. As a result, little evidence remains of the secular musical activity during the early centuries A.D., and we can more easily follow the evolution of singing as it is reflected in the development of sacred music, specifically that of the Latin-speaking Roman Church. THIRTEEN CENTURIES OF SACRED MUSIC In the fourth century A.D., Christianity became established as the official religion of the Roman Empire and a SCHOLA CANTORUM was founded by Pope Sylvester. The Roman Catholic Church would control the development of Western music for the next thirteen centuries, a span that saw music change from simple unison chant to the highly developed polyphonic choral style of Palestrina. This era was marked by a recurrent pattern, roughly three centuries in period, when the reigning Pope, concerned with the purity of the church's music, would order stylistic retrenchment and place new restraints on the creativity of those who were prone to elaborate the music of the MASS. Three styles of chant melody evolved: syllabic (for clergy and congregation), neumatic (several notes to a syllable, for choristers) and melismatic (florid, for soloists). Metricity in either chant texts or melodies was uncommon, but occurred as early as the fourth century. About 600 A.D., Pope Gregory (whence Gregorian chant) reorganized the Schola Cantorum . His reforms standardized the liturgical repertory and changed the character of the Christian service from unbridled ecstasy to subdued reverence. By 800 A.D., the repertory was again being enlarged with newly created material called TROPES. Plainchant manuscripts are extant from the ninth century, which was also when the first known examples of polyphony occurred and the deterioration of chant began--to continue into the thirteenth century--as its original simplicity was gradually effaced by the ongoing use of specialized singers and their introduction of ornamentation and virtuosic effects (see JUBILUS ). About the tenth century, musical notation began suggesting pitch movement by placing symbols above or below a horizontal line and the slow development of multiple-line staffs began. In the graphic art of the Middle Ages, singers were often shown with strained expressions, their furrowed brows, protruding veins and exaggerated mouth positions suggesting an effortful, possibly nasal quality--twangy or reedy--like the instrumental colors of the time. Chaucer, in his fourteenth century Canterbury Tales, described singing of the time as being 'intoned through the nose'. Straight tone was the probable norm, with vibrato being reserved for use as an ornament, as were a stock of ancient vocal devices: portamenti, turns, trills, and the intentional use of the qualities of the various vocal registers. The yodel was probably used as well. THE RISE OF POLYPHONY The idea of high and low pitched voices arose with the coming of polyphony in the ninth century. As polyphony developed in complexity, better educated singers were required, and one of the training devices created (by Guido D'Arezzo, 11th century) was the Guidonian Hand, the basis of a sightreading technique, SOLMIZATION, still used today. By the eleventh century, portamenti were being used on certain consonants in chant performance and the singing of descants had begun. These were elaborations performed against a cantus firmus, the protracted notes of a plainchant melody. Those who sustained the prolonged notes were called 'holders' or tenors, while those who sang the descant part 'against' them were called contratenors. The contratenors often sang the 'high' part, eventually called the altus , and, later, those who sang a part intertwining with the altos were named--predictably--contraltos. Eventually these parts were surrounded by two outer contrapuntal voices, appropriately named sopranus (above) and bassus (below). Organum was the name given to early polyphony (800-1250 A.D.). Simple organum used two voice parts that sang in parallel fourths or fifths and eventually these two voices were doubled at the octave. Free organum (11th-12th centuries) employed an expanded harmonic vocabulary, allowing perfect fourths, major and minor thirds and the major second, while fifths and semitones were avoided. Parallel, oblique and contrary motion and crossing voices were increasingly used to obtain pleasing harmonies and to avoid the tritone, which was held to be 'the devil in music'. As polyphony developed (14th-17th centuries) rhythmic notation was introduced. The fourteenth century ars nova (new art) style developed bolder harmonies, required wider vocal ranges and used more interesting rhythms (though bar lines would not be introduced until late in the sixteenth century). Though ever higher treble voices were needed, the Church could not resign itself to the use of female voices (proscribed in I Corinthians 14:34) and turned instead to the increased use of boys with unchanged voices (putti ). But boys suffered the drawback of having relatively brief useful careers after their protracted training, and the next step was to use mature males singing in the falsetto register. The fifteenth century saw the Council of Trent attempt to restore purity to the liturgy by outlawing the use of such elaborative material as tropes and SEQUENCES. It also saw important new activity in the creation of polyphonic Masses and MOTETS. As the developing contrapuntal style generated interest in the range and timbre differences of the lower male voices, the last primary voice-type term, baritone (Greek for 'weighty sound'), came into use. Then, from Spain (where Moorish harem-guard eunuchs had been the probable models), came the first castrati. These were adult singers whose testicles had been surgically removed before puberty. (Youthful castration stabilized the infantile larynx and resulted in the development of an unusually large rib cage. Both soprano and alto voices resulted.) A castrato first joined the putti and falsettists (now called contraltini ) in the Papal Choir late in the sixteenth century. This was also when the rich polyphonic choral style of the Renaissance would end--while at its very peak-to be replaced by a revolutionary new musical style centered on soloistic vocalism: monody. The happenstance that a number of leading choral composers (Gabrieli, Gesualdo, Guerrero, Hassler, le Jeune, di Lasso, Merulo, Morley, Nanini, Palestrina and de Victoria) all died within the span of twenty years (1594-1614), helps explain the abruptness with which the great polyphonic choral era ended. The nuove musiche (new music) style that began the Baroque period (1600-1750) was homophonic, and featured a melodic line supported by a vertically conceived harmonic accompaniment. From our modern vantage point it may be impossible to appreciate what a remarkable idea this was, but at a time when music was almost exclusively contrapuntal and each voice was horizontally conceived and of equal importance to those around it, it must have been revolutionary. The homophonic style is typified by the Protestant hymn or Chorale, and it may have been that the sixteenth-century Reformation movement--which used vernacular language in worship and expected its congregational members to participate in singing during the service--gave impetus to the use of the new, relatively simple homophony. THE RISE OF THEATRICAL MUSIC Though their purpose was to recreate ancient Greek drama, the FLORENTINE CAMERATA effectively established a completely new manner. Their operas (works) were what we would consider classical plays, sung throughout in a formless, text-centered recitative. Yet they altered the history of music by opening a new venue for musical creativity and performance--the secular world of the theater. The impact this had on singing was revolutionary: women's voices could be used, dramatic expressiveness entered the realm of singing, the skills of moving and acting while singing had to be learned and the reverberant acoustic of the church was traded for the less favoring design of the theater. Also, a new and competitive presence, the instrumental accompaniment, was developing. The old unaccompanied style, with its relative ease of emission, would soon be reserved for use 'in the church'--a cappella. Attending and heightening this time of artistic disjuncture would be the fundamental transition from modality to major-minor tonality. GLOSSARY of terms capitalized in the text. CHEIRONOMY or CHIRONOMY: Before the era of musical notation ensemble singing was often guided by a leader making hand signals to show pitches. A similar idea, the Curwin Hand Sign System, is in active use today. FLORENTINE CAMERATA: A group of artists intellectuals and musicians who, in Florence, at the end of the sixteenth century, often met to discuss ancient Greek drama and its performance style. JUBILUS: In early plainchant, an ornamental vocalization that was sung on the final vowel of the word alleluia. It was so popular with liturgical performers its use survived even the reforms of Pope Gregory, c. 600. MASS: The basic liturgical structure of the Roman Catholic sacred service and the music that attends it. The Mass developed over many centuries, and two categories of material came to make up its form: the Ordinary (items ordinarily present in every Mass) and the Proper (items inserted when proper to the occasion). Sung elements of the Ordinary are the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei. In the Proper, such sung sections as the Introit, Gradual, Alleluia, Offertory and Communion may occur. Portions of the Mass have been sung in plainchant since the earliest history of the Church, and for four centuries (1200 to 1600 A.D.) the polyphonic Mass was the primary format for serious musical composition. MOTET: An unaccompanied choral anthem intended for performance in the Catholic sacred service. It was an important form of composed music and underwent considerable change during its long span of active use (1250-1750 A.D.). PYTHAGOREAN SCALE: An eight-tone diatonic scale the Greek mathematician Pythagoras (c. 550 B.C.) created by reordering the tones he derived from a circle of fifths. SCHOLA CANTORUM: A training school for the papal choir in Rome. It became the center for the development and dissemination of the church's music and sent out singers to other churches. SEQUENCES: The oldest and most important form of TROPE, originally occurring on the alleluia of the Mass. Unlike older chant, this newly created material often used expanded vocal ranges and formal compositional devices such as melodic sequence. SOLMIZATION: A music reading method that associates syllables (do, re, mi, etc.) with pitches of the diatonic scale. Many ancient cultures had developed similar systems before this one was created for use in teaching sightreading to monks. TROPES: A textual addition to the official Catholic liturgy. Some were adapted to preexisting melismas (hence contrafacta ) but others were sung to new melodies freely derived from the plainchant melody. Continue on to Next Section Return to the Table of Contents