Ecological Impacts During the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

Ecological Impacts during the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

Mace G Barron

Gulf Ecology Division, US EPA

1 Sabine Island Drive, Gulf Breeze, FL 32561

Introduction

The Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill was the largest spill and response effort in

United States history. Nearly 800 million L of oil was spilled in the Gulf of Mexico, and nearly 7 million L of chemical dispersants were applied in at the ocean surface and subsea

1

. The DWH spill was a deep ocean well blowout that occurred on April 20, 2010 at a depth of 1600 meters,

66 km offshore of Louisiana. Estimates of the leak were continually revised from initial values of

795,000 L per day to final estimates of 9.8 million L per day. Approximately 180,000 km

2 of the

Gulf of Mexico had visible oiling of surface water (Fig. 1). Spill response countermeasures used to reduce or remove oil at the ocean surface included oil collection from the wellhead, surface oil skimming, in situ burning, and subsurface wellhead and aerial applications of chemical dispersants 2 . Multiple attempts to cap or close the well occurred during the three month spill, with successful capping on July 15, 2010; the well was declared closed on September 19, 2010.

This presentation is focused on impacts and events during the three month spill, including major

Federal and multi-stake holder research efforts that included dispersant testing, estimation of spill rate and oil fate, subsea assessments, shoreline and wildlife oiling determinations, and coastal condition assessment.

Dispersant Testing

USEPA performed a series of laboratory tests to determine the efficacy and toxicity of eight dispersants that were listed on the Product Schedule of the National Contingency Plan

3

, including Corexit 9500, which was the dispersant predominantly applied during the DWH spill.

The results of this testing program indicated that Corexit 9500 had similar efficacy and toxicity

4 as the other tested products.

Estimating Spill Rate and Oil Fate

A consensus estimate of the rate of oil release from the wellhead was developed by the

Flow Rate Technical Group based on high resolution videography. A value of 9.8 million L/d, was used in the calculation of the oil budget 5 . The fate of the spilled oil was calculated by the team of scientists and engineers in the Federal Interagency Solutions Group based on estimates of leak rate and surface behavior, dissolution, evaporation, weathering by emulsification, natural and chemical dispersion, in situ burning, and mechanical recovery (FISC, 2010). These calculations show that about 20% of the oil was recovered at the well head or through skimming, and about 35% dissipated through natural processes. There was high uncertainty in the amount of oil chemically dispersed (10 to 29%) and remaining as residual oil (11 to 30%)

5

.

Subsea Plume Assessment

An extensive assessment of deep water plume size and trajectory, and potential dissolved oxygen depressions due to oil degradation and dispersion were conducted during the DWH spill by the Joint Analysis Group

6

. The JAG concluded that fluorescence spectroscopy, dissolved oxygen, and petroleum chemistry vertical profiles were indicative of a deep water plume at 1100 to 1400 m that was consistent with water movement patterns near the well head

6

. The JAG also

concluded that subsea dissolved oxygen depressions did not approach hypoxic levels and were stable after August 2010

6

.

Near-term Impact Assessments

More than 1600 km of Gulf of Mexico shoreline were visibly oiled during the DWH spill.

Maximum oiling occurred along the shorelines and barrier islands of Louisiana, Mississpi,

Alabama, and western Florida, as well as wetland areas of Louisiana (Fig. 1). Shoreline cleaning and natural processes have removed a substantial amount of the oil from these areas, leaving a limited number of areas with clean up still in progress

1

. Several large scale sampling, monitoring, and assessments of subsea, onshore and offshore water and sediment were performed during the spill to both guide post-spill oil removal and to determine near-term impacts from the spill.

Based on thousands of available samples, research cruises and field efforts, the

Operational Science Advisory Team (OSAT) concluded there were no deposits of liquid phase

DWH oil beyond the shoreline, no exceedences of human health or dispersant toxicity benchmarks, and less than 1% incidence of water and sediment samples exceeding aquatic toxicity benchmarks

7

. A second OSAT assessment was conducted specifically to determine if beach cleanup should continue. OSAT reported that 80% of PAHs in the residual oil present in the beach environment had been depleted, and there were minimal risks of leaching of buried oil

8

. The report concluded that there would be greater impacts to wildlife from continuing beach clean up compared to leaving the residual oil in place, and there were continuing risks to shore birds from ingestion of residual oil and to the eggs and hatchlings of sea turtles from buried oil

8

.

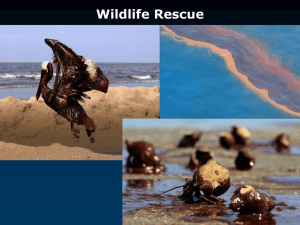

Reported wildlife oiling during the DWH spill included observations of oiled birds, sea turtles, and dolphins. There were nearly 10,000 bird observations, including 2085 categorized as visibly oiled alive, and 2303 visibly oiled dead

9

. Figure 2 shows the spatial distribution of avian oiling observations. Oil impacts on marine mammals included 140 dead animals and numerous dolphin strandings.

The impacts of the DWH spill on the condition of near coastal areas and estuaries was assessed using a variety of sediment and water quality indicators, including analytical chemistry measurements in water, sediment and tissues, and benthic organism surveys and toxicity testing.

Sampling was performed between April and September with the indicators (including specific chemical analytes) and sample locations varying across the surveys. Baseline information was available from previous regional surveys 1 . Comparison of the condition information across surveys indicated some impacts during the spill, but minimal impacts after the well was capped

9

.

Natural Resource Damage Assessment

The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA) established liability for the discharge and substantial threat of a discharge of oil to navigable waters and shorelines. The responsibility for acting on behalf of the public lies with designated Federal, state, tribal, and natural resource trustees. Trustees for the DWH spill include the U.S. Departments of Commerce, Interior and

Defense, USDA, USEPA and the five affected states (TX, LA, MS, AL, FL). The Natural

Resource Damage Asssessment is ongoing and has included over 90 offshore cruises and 30,000 samples of water, sediment, tissues, and oil from the deep ocean, offshore, and coastal areas 10 .

Transmitters have been placed in whale sharks, bluefin tuna, and sperm whales to assess exposures to pelagic species. Other activities included complex modeling of oil distribution, fate and effects, and toxicity testing of multiple species. Over 7000 km of shoreline have been

surveyed for oil impacts. The conclusions of the Natural Resource Damage Assessment may not be available for several years.

Conclusions

The affected areas of the Gulf of Mexico included a diversity of environments, including the deep ocean, offshore pelagic areas, and coastal beaches and wetlands. Multiple species of pelagic, tidal, and estuarine organisms, sea turtles, marine mammals and birds were impacted, and over 20 million hectares of the Gulf of Mexico were closed to fishing during the DWH spill

(Fig. 3). Impacts to the deep ocean will be difficult to determine and remain uncertain. Initial reports suggest developmental toxicity to early life stages of aquatic organisms were likely, that coastal wetlands are recovering, and that some oil persists. Seafood has been deemed safe by

Federal agencies and fishery closures have been removed, but there have been periodic anecdotal reports of unexplained physical abnormalities in fish, shrimp, and dolphins. The assessment of impacts to the Gulf of Mexico is ongoing, and may require years to complete because of the complexity and diversity of the affected species and environments, and the presense of multiple existing stressors with complex interactions between the spilled oil, fishing pressure, natural mortality and changing environmental conditions.

References

1. Barron, MG. (2012). Ecological impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill: implications for immuntoxicity. Toxicol Path 40:315-320.

2. Carriger, J and MG Barron. 2011. Minimizing risks from spilled oil to ecosystem services using influence diagrams: The Deepwater Horizon spill response.

45:7631-7639

Environ Sci Technol

3. USEPA. (2011). Environmental Protection Agency National Contingency Plan Product

Schedule. Office of Emergency management. June 2011. http://www.epa.gov/emergencies/docs/oil/ncp/schedule.pdf

4. Hemmer, MJ, MG Barron and R Greene. (2011). Comparative toxicity of eight oil dispersants, Louisiana sweet crude oil (LSC) and chemically dispersed LSC to two aquatic test species. Environ Tox Chem 30:2244-2252.

5. FISC. (2010). Oil budget Calculator, Deepwater Horizon. Technical Documentation, A

Report to the National Incident Command. Federal Interagency Solutions Group (FISC).

November, 2010.

6. JAG. (2011). Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, Joint Analysis Group.

[www.ncddc.noaa.gov/activities/healthy-oceans/jag/reports]

7. OSAT. (2010). Summary Report for Sub-Sea and SubSurface Oil and Dispersant

Detection: Sampling and monitoring. Operational Science Advisory Team (OSAT).

Prepared from U.S. Coast Guard. December 2010.

[ www.restorethegulf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/OSAT_Report_FINAL_17DE

C.pdf

]

8. OSAT. (2011). Summary Report for Fate and Effects of Remnant Oil Remaining in the

Beach Environment. Operational Science Advisory Team (OSAT-2). Prepared from U.S.

Coast Guard. http://www.restorethegulf.gov/sites/default/files/u316/OSAT-

2%20Report%20no%20ltr.pdf

February 2011.

9. USFWS. (2011). Deepwater horizon Response Consolidated Fish and Wildlife Collection

Report. April 20, 2011. http://www.fws.gov/home/dhoilspill/pdfs/ConsolidatedWildlifeTable042011.pdf

10.

NOAA DOI. (2011). Assessing the impacts of oil: Next Steps. Fact Sheet. Deepwater

Horizon BP oil spill, Natural Resource Damage Assessment. March 2011. http://www.gulfspillrestoration.noaa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/NRDA-NEXT-

STEPS-DOI-NOAA-JOINT-3-11.pdf

March 2011.

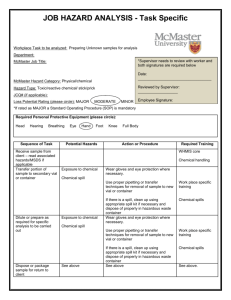

Figure 1. Cumulative surface water oiling (days) and maximum shoreline oil (none to heavy) during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Map created April 2013 using the NOAA Environmental

Response Management Application ( http://Gomex.erma.noaa.gov/erma.html

).

Figure 2. Reported avian oiling observations during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Map created April 2013 using the NOAA Environmental Response Management Application

( http://Gomex.erma.noaa.gov/erma.html

).

Figure 3. Boundaries of Federal fishery closures during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (May 2-

Oct 22, 2010). Map created April 2013 using the NOAA Environmental Response Management

Application ( http://Gomex.erma.noaa.gov/erma.html

).