Classic Play Monologues: Moliere, Wilde, Chekov

advertisement

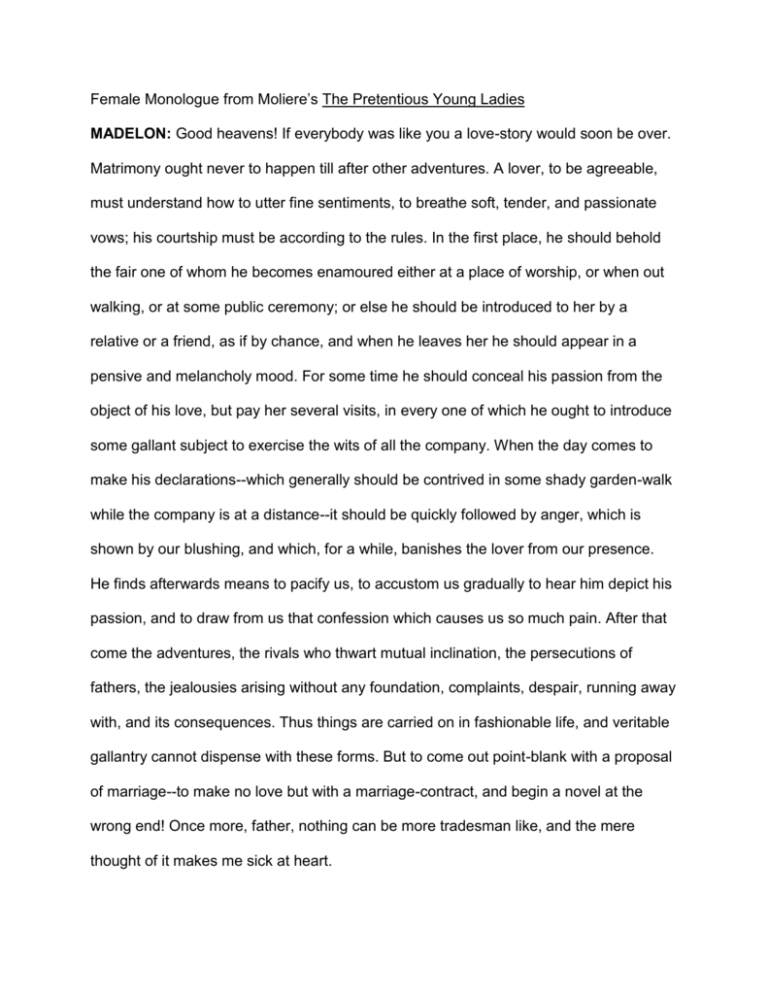

Female Monologue from Moliere’s The Pretentious Young Ladies MADELON: Good heavens! If everybody was like you a love-story would soon be over. Matrimony ought never to happen till after other adventures. A lover, to be agreeable, must understand how to utter fine sentiments, to breathe soft, tender, and passionate vows; his courtship must be according to the rules. In the first place, he should behold the fair one of whom he becomes enamoured either at a place of worship, or when out walking, or at some public ceremony; or else he should be introduced to her by a relative or a friend, as if by chance, and when he leaves her he should appear in a pensive and melancholy mood. For some time he should conceal his passion from the object of his love, but pay her several visits, in every one of which he ought to introduce some gallant subject to exercise the wits of all the company. When the day comes to make his declarations--which generally should be contrived in some shady garden-walk while the company is at a distance--it should be quickly followed by anger, which is shown by our blushing, and which, for a while, banishes the lover from our presence. He finds afterwards means to pacify us, to accustom us gradually to hear him depict his passion, and to draw from us that confession which causes us so much pain. After that come the adventures, the rivals who thwart mutual inclination, the persecutions of fathers, the jealousies arising without any foundation, complaints, despair, running away with, and its consequences. Thus things are carried on in fashionable life, and veritable gallantry cannot dispense with these forms. But to come out point-blank with a proposal of marriage--to make no love but with a marriage-contract, and begin a novel at the wrong end! Once more, father, nothing can be more tradesman like, and the mere thought of it makes me sick at heart. Female Monologue from Fourteen, by Alice Gerstenberg MRS. PRINGLE: I shall go mad! I'll never entertain again--never--never--people ought to know whether they're coming or not--but they accept and regret and regret and accept--they drive me wild. This is my last dinner party--my very last--a fiasco--an utter fiasco! A haphazard crowd--hurried together--when I had planned everything so beautifully--now how shall I seat them--how shall I seat them? If I put Mr. Tupper here and Mrs. Conley there then Mrs. Tupper has to sit next to her husband and if I want Mr. Morgan there--Oh! It's impossible--I might as well put their names in a hat and draw them out at random--never again! I'm through! Through with society--with parties--with friends--I wipe my slate clean--they'll miss my entertainments--they'll wish they had been more considerate--after this, I'm going to live for myself! I'm going to be selfish and hard--and unsociable--and drink my liquor myself instead of offering it gratis to the whole town!--I'm through--Through with men like Oliver Farnsworth!--I don't care how rich they are! How influential they are--how important they are! They're nothing without courtesy and consideration--business--off on train--nonsense--didn't want to come-didn't want to meet a sweet, pretty girl--didn't want to marry her--well, he's not good enough for you!--don't you marry him! Don't you dare marry him! I won't let you marry him! Do you hear? If you tried to elope or anything like that, I'd break it off--yes, I would-Oliver Farnsworth will never get recognition from me!--He is beneath my notice! I hate Oliver Farnsworth! Female Monologue from An Ideal Husband, by Oscar Wilde MABEL CHILTERN: Well, Tommy has proposed to me again. Tommy really does nothing but propose to me. He proposed to me last night in the music-room, when I was quite unprotected, as there was an elaborate trio going on. I didn't dare to make the smallest repartee, I need hardly tell you. If I had, it would have stopped the music at once. Musical people are so absurdly unreasonable. They always want one to be perfectly dumb at the very moment when one is longing to be absolutely deaf. Then he proposed to me in broad daylight this morning, in front of that dreadful statue of Achilles. Really, the things that go on in front of that work of art are quite appalling. The police should interfere. At luncheon I saw by the glare in his eye that he was going to propose again, and I just managed to check him in time by assuring him that I was a bimetallist. Fortunately I don't know what bimetallism means. And I don't believe anybody else does either. But the observation crushed Tommy for ten minutes. He looked quite shocked. And then Tommy is so annoying in the way he proposes. If he proposed at the top of his voice, I should not mind so much. That might produce some effect on the public. But he does it in a horrid confidential way. When Tommy wants to be romantic he talks to one just like a doctor. I am very fond of Tommy, but his methods of proposing are quite out of date. I wish, Gertrude, you would speak to him, and tell him that once a week is quite often enough to propose to any one, and that it should always be done in a manner that attracts some attention. Female Monologue from A Woman of No Importance, by Oscar Wilde MRS. ALLONBY: The Ideal Man! Oh, the Ideal Man should talk to us as if we were goddesses, and treat us as if we were children. He should refuse all our serious requests, and gratify every one of our whims. He should encourage us to have caprices, and forbid us to have missions. He should always say much more than he means, and always mean much more than he says. He should never run down other pretty women. That would show he had no taste, or make one suspect that he had too much. No; he should be nice about them all, but say that somehow they don't attract him. If we ask him a question about anything, he should give us an answer all about ourselves. He should invariably praise us for whatever qualities he knows we haven't got. But he should be pitiless, quite pitiless, in reproaching us for the virtues that we have never dreamed of possessing. He should never believe that we know the use of useful things. That would be unforgivable. But he should shower on us everything we don't want. He should persistently compromise us in public, and treat us with absolute respect when we are alone. And yet he should be always ready to have a perfectly terrible scene, whenever we want one, and to become miserable, absolutely miserable, at a moment's notice, and to overwhelm us with just reproaches in less than twenty minutes, and to be positively violent at the end of half an hour, and to leave us for ever at a quarter to eight, when we have to go and dress for dinner. And when, after that, one has seen him for really the last time, and he has refused to take back the little things he has given one, and promised never to communicate with one again, or to write one any foolish letters, he should be perfectly broken-hearted, and telegraph to one all day long, and send one little notes every half-hour by a private hansom, and dine quite alone at the club, so that every one should know how unhappy he was. And after a whole dreadful week, during which one has gone about everywhere with one's husband, just to show how absolutely lonely one was, he may be given a third last parting, in the evening, and then, if his conduct has been quite irreproachable, and one has behaved really badly to him, he should be allowed to admit that he has been entirely in the wrong, and when he has admitted that, it becomes a woman's duty to forgive, and one can do it all over again from the beginning, with variations. Male Monologue from Chekov’s The Boor SMIRNOV: I don't understand how to behave in the company of ladies. Madam, in the course of my life I have seen more women than you have sparrows. Three times have I fought duels for women, twelve I jilted and nine jilted me. There was a time when I played the fool, used honeyed language, bowed and scraped. I loved, suffered, sighed to the moon, melted in love's torments. I loved passionately, I loved to madness, loved in every key, chattered like a magpie on emancipation, sacrificed half my fortune in the tender passion, until now the devil knows I've had enough of it. Your obedient servant will let you lead him around by the nose no more. Enough! Black eyes, passionate eyes, coral lips, dimples in cheeks, moonlight whispers, soft, modest sights--for all that, madam, I wouldn't pay a kopeck! I am not speaking of present company, but of women in general; from the tiniest to the greatest, they are conceited, hypocritical, chattering, odious, deceitful from top to toe; vain, petty, cruel with a maddening logic and in this respect, please excuse my frankness, but one sparrow is worth ten of the aforementioned petticoat-philosophers. When one sees one of the romantic creatures before him he imagines he is looking at some holy being, so wonderful that its one breath could dissolve him in a sea of a thousand charms and delights; but if one looks into the soul--it's nothing but a common crocodile. But the worst of all is that this crocodile imagines it is a masterpiece of creation, and that it has a monopoly on all the tender passions. May the devil hang me upside down if there is anything to love about a woman! When she is in love, all she knows is how to complain and shed tears. If the man suffers and makes sacrifices she swings her train about and tries to lead him by the nose. You have the misfortune to be a woman, and naturally you know woman's nature; tell me on your honor, have you ever in your life seen a woman who was really true and faithful? Never! Only the old and the deformed are true and faithful. It's easier to find a cat with horns or a white woodcock, than a faithful woman. Male Monologue from Don Juan, by Moliere DON JUAN: What! would you have a man bind himself to the first girl he falls in love with, say farewell to the world for her sake, and have no eyes for anyone else? A fine thing, to be sure, to pride oneself upon the false honour of being faithful, to lose oneself in one passion for ever, and to be blind from our youth up to all the other beautiful women who can captivate our gaze! No, no; constancy is the share of fools. Every beautiful woman has a right to charm us, and the privilege of having been the first to be loved should not deprive the others of the just pretensions which the whole sex has over our hearts. As for me, beauty delights me wherever I meet with it, and I am easily overcome by the gentle violence with which it hurries us along. It matters not if I am already engaged: the love I have for a fair one cannot make me unjust towards the others; my eyes are always open to merit, and I pay the homage and tribute nature claims. Whatever may have taken place before, I cannot refuse my love to any of the lovely women I behold; and, as soon as a handsome face asks it of me, if I had ten thousand hearts I would give them all away. The first beginnings of love have, besides, indescribable charms, and the true pleasure of love consists in its variety. It is a most captivating delight to reduce by a hundred means the heart of a young beauty; to see day by day the gradual progress one makes; to combat with transport, tears, and sighs, the shrinking modesty of a heart unwilling to yield; and to force, inch by inch, all the little obstacles she opposes to our passion; to overcome the scruples upon which she prides herself, and to lead her, step by step, where we would bring her. But, once we have succeeded, there is nothing more to wish for; all the attraction of love is over, and we should fall asleep in the tameness of such a passion, unless some new object came to awake our desires and present to us the attractive perspective of a new conquest. In short, nothing can surpass the pleasure of triumphing over the resistance of a beautiful maiden; and I have in this the ambition of conquerors, who go from victory to victory, and cannot bring themselves to put limits to their longings. There is nothing that can restrain my impetuous yearnings. I have a heart big enough to be in love with the whole world; and, like Alexander, I could wish for other spheres to which I could extend my conquests. Male Monologue from Don Juan, by Moliere SGANARELLE: If you knew the man as I do, you would find it no hard matter to believe. I have no proof as yet. You know that I was ordered to start before him, and we have had no talk together since his arrival; but it is as a kind of warning that I tell you, inter nos, that you see in Don Juan, my master, one of the greatest scoundrels that ever trod the earth; a madman, a dog, a demon, a Turk, a heretic who believes neither in heaven, saints, God, nor devil; who spends his life like a regular brute, an epicurean hog; a true Sardanapalus, who shuts up his ears against all the admonitions that can be made to him, and who laughs at everything we believe in. You say that he has married your mistress; believe me, in order to satisfy his passion, he would have done more, and married along with her not only yourself, but her dog and her cat into the bargain. A marriage is nothing to him: it is the grand snare he makes use of to catch the fair sex. He is a wholesale marriage-monger; gentlewomen, young girls, middle-class women, peasant lasses, nothing is either too hot or too cold for him; and if I were to tell you the names of all those he has married in different places, the chapter would last from now till midnight. You seem surprised, and you grow pale; yet this is but a mere outline of the man, and to make a finished portrait we should require many more vigorous touches. Let it be sufficient that the wrath of Heaven must sooner or later make an end of him. He cannot escape; and it would be better for me to belong to the devil than to him. I am the witness of so much evil that I could wish him to be I don't know where. But if a great lord is also a wicked man, it is a terrible thing. I must be faithful to him, whatever I may think; in me fear takes the place of zeal, curbs my feelings, and often compels me to applaud what I most detest.-- Here he is, coming for a walk in this palace; let us part. But, listen: I have told you this in all frankness, and it has slipped rather quickly out of my mouth; but, if anything of what I have said should reach his ears, I would stoutly maintain that you have told a lie. Male Monologue from A Woman of No Importance, by Oscar Wilde Mother, how changeable you are! You don't seem to know your own mind for a single moment. An hour and a half ago in the Drawing-room you agreed to the whole thing; now you turn round and make objections, and try to force me to give up my one chance in life. Yes, my one chance. You don't suppose that men like Lord Illingworth are to be found every day, do you, mother? It is very strange that when I have had such a wonderful piece of good luck, the one person to put difficulties in my way should be my own mother. Besides, you know, mother, I love Hester Worsley. Who could help loving her? I love her more than I have ever told you, far more. And if I had a position, if I had prospects, I could - I could ask her to - Don't you understand now, mother, what it means to me to be Lord Illingworth's secretary? To start like that is to find a career ready for one - before one - waiting for one. If I were Lord Illingworth's secretary I could ask Hester to be my wife. As a wretched bank clerk with a hundred a year it would be an impertinence. Then I have my ambition left, at any rate. That is something - I am glad I have that! You have always tried to crush my ambition, mother - haven't you? You have told me that the world is a wicked place, that success is not worth having, that society is shallow, and all that sort of thing - well, I don't believe it, mother. I think the world must be delightful. I think society must be exquisite. I think success is a thing worth having. You have been wrong in all that you taught me, mother, quite wrong. Lord Illingworth is a successful man. He is a fashionable man. He is a man who lives in the world and for it. Well, I would give anything to be just like Lord Illingworth.