The Black Eagle Project - Eagles Fare Restaurant

advertisement

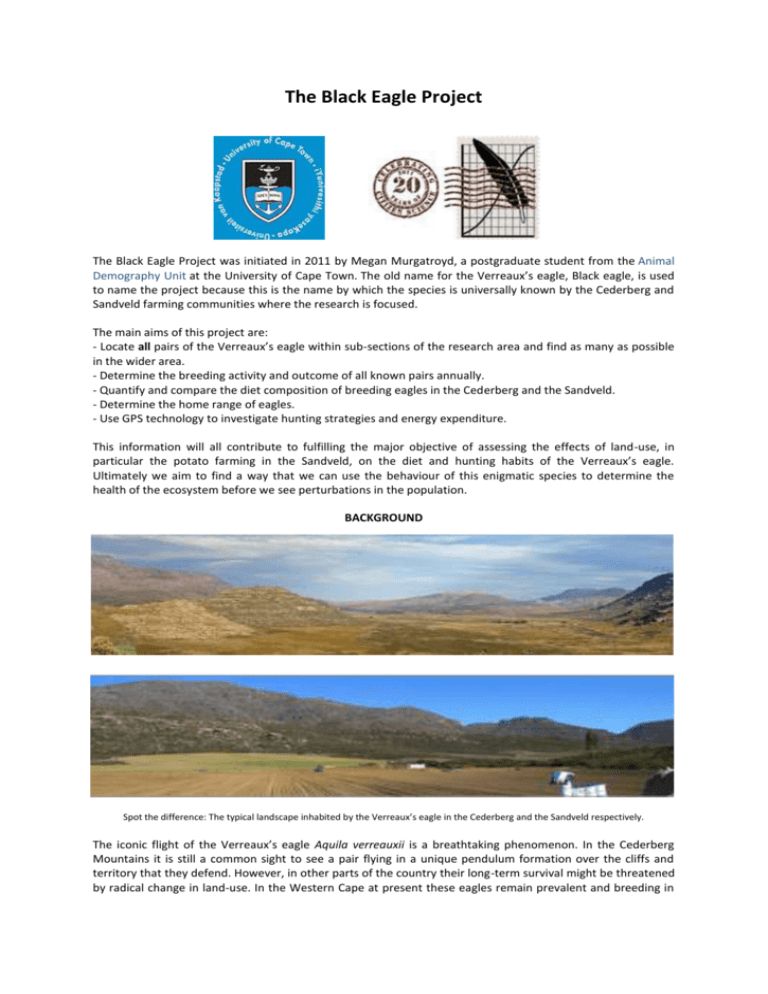

The Black Eagle Project The Black Eagle Project was initiated in 2011 by Megan Murgatroyd, a postgraduate student from the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town. The old name for the Verreaux’s eagle, Black eagle, is used to name the project because this is the name by which the species is universally known by the Cederberg and Sandveld farming communities where the research is focused. The main aims of this project are: - Locate all pairs of the Verreaux’s eagle within sub-sections of the research area and find as many as possible in the wider area. - Determine the breeding activity and outcome of all known pairs annually. - Quantify and compare the diet composition of breeding eagles in the Cederberg and the Sandveld. - Determine the home range of eagles. - Use GPS technology to investigate hunting strategies and energy expenditure. This information will all contribute to fulfilling the major objective of assessing the effects of land-use, in particular the potato farming in the Sandveld, on the diet and hunting habits of the Verreaux’s eagle. Ultimately we aim to find a way that we can use the behaviour of this enigmatic species to determine the health of the ecosystem before we see perturbations in the population. BACKGROUND Spot the difference: The typical landscape inhabited by the Verreaux’s eagle in the Cederberg and the Sandveld respectively. The iconic flight of the Verreaux’s eagle Aquila verreauxii is a breathtaking phenomenon. In the Cederberg Mountains it is still a common sight to see a pair flying in a unique pendulum formation over the cliffs and territory that they defend. However, in other parts of the country their long-term survival might be threatened by radical change in land-use. In the Western Cape at present these eagles remain prevalent and breeding in the Sandveld. Yet this area is now classed as the second most highly threatened ecosystem in South Africa and at least 50% of the land has been converted for agriculture (C.A.P.E. 2008; Low 2004). The main focus of the project is the Verreaux’s eagle and its main prey, the Rock hyrax Procavia capensis. In particular, the project aims to measure the impacts of land-use on the diet and hunting behaviour of these eagles by researching and comparing those breeding in the Cederberg Mountains and those in the Sandveld. We are taking an ecosystem approach. As a top predator this eagle is vulnerable to perturbations to the environment at any lower trophic level. As an umbrella species, successful conservation of the Verreaux’s eagle is dependent on the entire ecosystem remaining healthy. At the same time, the conservation of this top predator helps enable the ecosystem to remain healthy by preventing trophic cascades, the process whereby the loss of a predator enables a prey species to increase in abundance in such a way that the stability of the ecosystem is disturbed. The distribution of this eagle coincides closely with that of their staple food, the Rock hyrax. Habitat change appears to be a cause of declining prey availability for the Verreaux’s eagle. Declines in the Rock hyrax are thought to be the major driver behind losses of the Verreaux’s eagle from former breeding grounds. For example on the Cape Peninsula the number of breeding pairs has gone from at least five to just one in the last 20 years (Jenkins & van Zyl 2009; Rodrigues). SABAP and Citizen Science The first Southern African Bird Atlas Project (SABAP) 1 took place in the early 1990s and a subsequent one, SABAP2 began in 2007. SABAP is a citizen science project hosted by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town. Any keen birders can register as an observer and their data will contribute in a big way to detecting changes in avian populations throughout Southern Africa. So far throughout the project there have 1022 voluntary participants. This is a comparison map of data generated by the first and second bird atlas projects for the Verreaux’s Eagle in the Western Cape. Each square is a quarter degree grid cell (QDGC). The top and bottom numbers in each cell are the reporting rates for the QDGC respectively. The reporting rate is a measure of abundance. In red cells, Verreaux’s Eagles were recorded in SABAP1 but not in SABAP2. In orange cells the reporting rate has decreased. In yellow cells, reporting rates are identical. In green cells reporting rates have increased. Blue cells indicate where Verreaux’s Eagles were not recorded in SABAP1 but have in SABAP2 (this is most frequently likely to be due to poor coverage in SABAP1 rather than to genuine increases in range). In pink cells (which are mostly in the Northern Cape), the species was recorded in SABAP1, but have not yet been visited in SABAP2. The predominant shades in the Western Cape are red and orange, indicating range contractions and decreases in abundance of Verreaux’s Eagle. As a result of this the Verreaux’s eagle has been placed on ‘Special Watch’. Therefore you are invited to report ALL incidental sightings of this species. Over the next year I will be reviewing this data and will be reflecting upon the overall conservation status of this species in the Western Cape – this is a great way to be actively involved and I urge you to sign up! How do you find a nest? This is the first thing that everyone wants to know. In truth, I’m not telling! Eagles are sensitive to disturbance and over the years they have suffered from egg collectors and chick theft. Although these are diminishing trades all I’ll say is there is many kilometers of hiking involved in nest finding! How do you know the breeding success? Once the nest has been found all observations are made from a distance with a telescope. During the breeding season (May-Nov) I make regular visits to check for incubation, chicks and finally fledged young. Sometimes it can take hours to work out what is going on in a nest – you can’t see into them and if the adult is lying still incubating in the nest cup then you just have to wait and watch for the tip of a wing or tail feathers to flicker above the edge of the nest! When finally you get to see a chick being fed or standing on the edge of the nest and stretching its wings in preparation for its first flight… the reward is great! How do you analyze the diet? Sightings of eagles actually making a kill are few and far between. Although I often see an eagle carrying prey it is normally impossible to correctly identify what it is. Therefore we will be using two main techniques for the diet analysis. Firstly, we will install time-lapse nest cameras. These photos will enable us to identify prey species which are returned to the nest. The cameras will also give us important additional information such as the exact date of chick fledging which is normally very difficult to be accurate about. Secondly, we will analyze prey remains. After finishing with prey an adult eagle will carry the remains a short distance from the nest and drop them. I will be searching for these bone fragments at sites where access to the base of the cliff is possible. GPS technology What? Why? How?... coming soon!! Megan Murgatroyd Megan grew up in England with a fascination for African wildlife and wilderness. Her practical year of her degree (BSc Conservation biology, University of the West of England) took her to Namibia as a research assistant looking at the effects of diamond mining on the Damara tern. Since completing her degree she has worked for BirdWatch Ireland as a little tern warden, tried her hand at organic farming, and made an epic journey from Ethiopia to Cape Town by public transport! In 2010 she volunteered for the CLT in their Limietberg surveys and this was followed by founding the Black Eagle Project in 2011. The research which is being carried out will all contribute to her PhD with the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town.