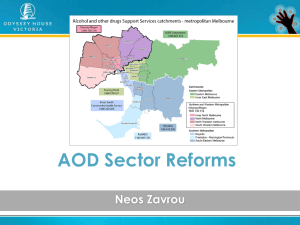

National Alcohol and other Drug Workforce Development Strategy

advertisement