systemic vasculitis

advertisement

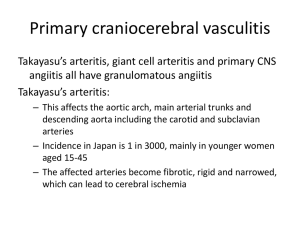

SYSTEMIC VASCULITIS Vasculitis is a nonspecific term that encompasses a large and heterogeneous group of disorders that are characterized by inflammation of blood vessels. The term "systemic necrotizing vasculitis" describes a systemic process in which blood vessel architecture has been destroyed by inflammatory cells. As described by Mandell and Hoffman,1 vasculitis-induced injury to blood vessels may lead to increased vascular permeability, vessel weakening that causes aneurysm formation or hemorrhage, and intimal proliferation and thrombosis that result in obstruction and local ischemia. Because systemic vasculitis can affect vessels of all sizes and distributions, it has a wide spectrum of clinical features. Knowing the size of the vessels affected in a particular patient is important, since vessel size carries implications for the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of the disease. It is critical to distinguish vasculitis occurring as a primary autoimmune disorder from vasculitis secondary to infection, drugs, malignancy or connective tissue disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or rheumatoid arthritis. Immunosuppressive therapy, which is sometimes used in the treatment of certain types of vasculitis, can have catastrophic consequences in the face of a systemic infection, as can delayed or inappropriate treatment of primary systemic vasculitis. Consequently, much of the diagnostic work-up in a patient with suspected vasculitis is directed at excluding secondary causes or conditions that can mimic vasculitis. When systemic vasculitis is suspected, the first step in the evaluation is to exclude other processes such as infection, thrombosis or neoplasia. Classification of Vasculitis Vasculitis may be classified by the size and type of vessel involvement, by the histopathologic features (leukocytoclastic, granulomatous vasculitis, etc.) or by the pattern of clinical features. Identifying the type of vasculitis is important, since certain types may be selflimited, whereas others may require corticosteroid therapy, with or without a cytotoxic agent, or other modalities such as plasmapheresis. Initially in the work-up, however, determining the extent of visceral organ involvement is more important than identifying the type of vasculitis, so that organs at risk of damage are not jeopardized if treatment is delayed or inadequate. The clinical features of primary vasculitis syndromes often overlap, and many patients do not fit neatly into a well-defined type of vasculitis. These patients may be described as having "undifferentiated systemic vasculitis." Such cases require close follow-up, looking for signs of involvement in other organs or signs that may lead to a specific diagnosis. Clinical Features and Primary Treatment of the Major Systemic Vasculitis Syndromes Systemic vasculitis Common presenting syndrome features Vasculitis of small vessels Hypersensitivity Palpable purpura vasculitis Henoch-Schönlein Palpable purpura, purpura arthritis, glomerulonephritis, intestinal ischemia Cryoglobulinemia Arthritis, Raynaud's phenomenon, glomerulonephritis, palpable purpura Vasculitis of small and medium-sized vessels Polyarteritis Peripheral neuropathy, nodosa mononeuritis multiplex, intestinal ischemia, renal ischemia, testicular pain, livedo reticularis Microscopic Pulmonary hemorrhage, polyangiitis glomerulonephritis Primary treatment Often self-limited if offending agent is removed. If isolated to skin, may not require therapy. In more severe cases, moderate- to high-dose corticosteroid therapy may be needed. Often self-limited and requires no treatment. Steroid therapy for some cases of gastrointestinal or renal involvement. Corticosteroids; plasmapheresis for severe involvement. Antiviral therapy required if associated with hepatitis C. High-dose corticosteroids, often with cytotoxic agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide [Cytoxan]) High-dose corticosteroids, often with cytotoxic agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide) Churg-Strauss vasculitis Wegener's granulomatosis Kawasaki disease Allergic rhinitis, asthma, eosinophilia, pulmonary infiltrates, coronary arteritis, intestinal ischemia Recurrent epistaxis or sinusitis, pulmonary infiltrates and/or nodules, glomerulonephritis, ocular involvement Fever, conjunctivitis, lymphadenopathy, desquamating rash, mucositis, arthritis, coronary artery aneurysms High-dose corticosteroids, often with cytotoxic agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide) High-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide. Corticosteroids and methotrexate may be used for less severe involvement. High-dose aspirin and intravenous immune globulin Vasculitis of large vessels Giant cell, or Headache, polymyalgia High-dose corticosteroids temporal, arteritis rheumatica, jaw or tongue claudication, scalp tenderness, fever, vision disturbances Takayasu's arteritis Extremity claudication, High-dose corticosteroids athralgias, constitutional symptoms, renal ischemia When to Suspect Systemic Vasculitis In particular, two types of presentation should alert the clinician to the possibility of systemic vasculitis: unexplained ischemia, such as claudication, limb ischemia, angina, transient ischemic attack, stroke, mesenteric ischemia and cutaneous ischemia, particularly in a young patient or a patient without risk factors for atherosclerosis and multiple organ dysfunction in a systemically ill patient, especially in the presence of other suggestive clinical features. Clinical Features That Raise Suspicion of Vasculiti General clinical feature Signs or presenting disorder Constitutional symptoms Polymyalgia rheumatica Type of vasculitis Fever, fatigue, malaise, Any type of vasculitis anorexia, weight loss Proximal muscle pain with Giant cell arteritis; less morning stiffness commonly, other vasculitides Nondestructive Joint swelling, warmth, Polyarteritis, Wegener's oligoarthritis painful range of motion granulomatosis, ChurgStrauss vasculitis Skin lesions Livedo reticularis, necrotic Polyarteritis, Churglesions, ulcers, nodules, Strauss vasculitis, digital tip infarcts Wegener's granulomatosis, hypersensitivity vasculitis Palpable purpura Any type of vasculitis except giant cell arteritis and Takayasu's arteritis Multiple Injury to two or more Polyarteritis, Churgmononeuropathy separate peripheral nerves Strauss vasculitis, (mononeuritis (e.g., patient presents with Wegener's multiplex) both right foot drop and granulomatosis, left wrist drop) cryoglobulinemia Renal involvement Ischemic renal failure Polyarteritis, Takayasu's related to arteritis arteritis; less commonly, Churg-Strauss vasculitis and Wegener's granulomatosis Glomerulonephritis Microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener's granulomatosis, cryoglobulinemia, ChurgStrauss vasculitis,HenochSchönlein purpura General Approach to Diagnosis When systemic vasculitis is suspected, the diagnostic work-up can be approached in a stepwise fashion: 1. Attempt to exclude other processes, particularly infection, thrombosis and neoplasia, that can cause secondary vasculitis or can have features that mimic vasculitis. This must be done quickly to provide appropriate therapy for a potentially life-threatening condition. In addition, anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapy of the systemic vasculitides is potentially toxic and may mask certain disorders, such as infection or a perforated viscus. Conditions That Can Mimic Primary Systemic Vasculitis Embolic disease Endocarditis Atrial myxoma Cholesterol embolization Vessel stenosis or "spasm" Atherosclerosis Fibromuscular dysplasia Drug-induced vasospasm (e.g., ergots, cocaine, phenylpropanolamine) Intravascular lymphoma Vessel thrombosis Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura Antiphospholipid antibody syndome Heparin- or warfarin-induced thrombosis Systemic infection Malignancy Other connective tissue disorders 2. Consider the patient's age, sex and ethnic origin, since certain vasculitis syndromes occur more commonly in specific populations. Demographic Associations of the Vasculitides Age group Male-tofemale ratio Child M=F M>F Young adult M=F Middle age Elderly F>M M>F F>M Ethnic origin Type of vasculitis Any Asian > white > others Middle Eastern > others Asian >> others Any Henoch-Schönlein purpura Kawasaki disease Caucasian >> others Behçet's disease Takayasu's arteritis Wegener's granulomatosis, polyarteritis, Churg-Strauss vasculitis Giant cell arteritis 3. Determine which organs are involved and estimate the size of vessel involvement. The type and extent of organ involvement in vasculitis can be helpful in determining the specific type of vasculitis and the degree of urgency in initiating treatment. The clinical features in a given patient can be used to discern the size of the vessels affected by vasculitis. It should be recognized that the terms "small," "medium" and "large" to describe vessel size have different meanings for a pathologist, an angiographer and a clinician. Clues for Identifying the type of Vessel Involvement in Vasculitis Clinical feature Cutaneous Palpable purpura Skin ulcers Gangrene in an extremity Gastrointestinal tract Abdominal pain or mesenteric ischemia Gastrointestinal bleeding Renal Glomerulonephritis Ischemic renal failure Pulmonary Pulmonary hemorrhage Most likely affected Most commonly associated systemic vessel vasculitis Postcapillary venules Any type of vasculitis except giant cell arteritis and Takayasu's arteritis Arterioles to small Polyarteritis, Churg-Strauss vasculitis, arteries Wegener's granulomatosis, hypersensitivity vasculitis Small to mediumPolyarteritis, Churg-Strauss vasculitis, sized arteries Wegener's granulomatosis Small to mediumsized arteries Capillaries to medium-sized arteries Henoch-Schönlein purpura, polyarteritis, Churg-Strauss vasculitis Henoch-Schönlein purpura, polyarteritis, Churg-Strauss vasculitis Capillaries Microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener's granulomatosis, cryoglobulinemia, Churg-Strauss vasculitis, HenochSchönlein purpura Polyarteritis, Takayasu's arteritis; less commonly, Churg-Strauss vasculitis and Wegener's granulomatosis Small to mediumsized arteries Capillaries; less commonly small to medium-sized arteries Microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener's granulomatosis Pulmonary infiltrates or cavities Neurologic Peripheral neuropathy Stroke Small to mediumsized arteries Churg-Strauss vasculitis, microscopic polyangiitis Small arteries Polyarteritis, Churg-Strauss vasculitis, Wegener's granulomatosis, cryoglobulinemia Small, medium-sized Giant cell arteritis, SLE-associated or large arteries vasculitis 4. Attempt to distinguish the specific type of vasculitis on the basis of the above information and the pattern of the clinical features. Laboratory Testing Although occasionally helpful in classifying vasculitis, laboratory testing is most important in determining organ involvement and excluding the presence of other diseases. Important routine tests include complete blood cell count, urinalysis, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine and liver enzyme levels. Leukocytosis, anemia of chronic disease, a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and an elevated C-reactive protein level are commonly found in most types of vasculitis. Although ESR is almost always elevated in vasculitis, a normal ESR does not rule out systemic vasculitis.1 If the patient has renal failure or proteinuria and hematuria on urinalysis, a fresh-spun urine sample should be evaluated for red blood cell casts or dysmorphic red cells that would suggest the presence of a glomerulonephritis. Laboratory Tests to Consider in the Evaluation of Systemic Vasculitis Laboratory test Purpose or interpretation Routine tests (including complete blood cell count, liver enzymes, creatinine, urinalysis) Blood cultures Erythrocyte sedimentation rate C-reactive protein Rheumatoid factor Evaluate for hematologic, renal and other organ involvement Rule out infection High value suggests inflammatory disease High value suggests inflammatory disease Very high titers in rheumatoid arthritis, Antinuclear antibody Complements (C3, C4, CH50) Cryoglobulins ANCA Creatine phosphokinase RPR/VDRL Serum protein electrophoresis Hepatitis B and C serology HIV Anti-glomerular basement membrane Sjögren's syndrome and cryoglobulinemiaassociated vasculitis Screen for SLE and Sjögren's syndrome Low complement levels suggest consumption by immune complexes, which are commonly found in SLE and cryoglobulinemia Must be present to diagnose mixed essential cryoglobulinemia but can be found in any primary or secondary vasculitis Cytoplasmic ANCA pattern specific for Wegener's granulomatosis; perinuclear ANCA pattern may occur in other vasculitides Elevation suggests myositis, which can occur in many vasculitis syndromes Rule out syphilis Evaluate for plasma cell dyscrasias Rule out hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection Rule out HIV infection Rule out Goodpasture's syndrome, which can mimic vasculitis and cause pulmonary hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; ANCA = anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; RPR = rapid plasmin reagin; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus. Chest radiographs may reveal asymptomatic pulmonary involvement. If findings suggestive of peripheral neuropathy or muscle inflammation are noted on the history and physical examination, nerve conduction velocity and electromyographic testing can help confirm these suspicions and serve as a guide for biopsy. Although rheumatoid factor can be present in any inflammatory disease, it is more often found in rheumatoid arthritisassociated vasculitis, Sjögren's syndrome and mixed cryoglobulinemia. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies should be obtained, since these infections are sometimes associated with vasculitis.8-10 While complement levels (C3, C4 and CH50) are often normal or high in other types of vasculitis, they tend to be low in SLE-associated vasculitis, cryoglobulinemia and hepatitis B and Cassociated vasculitis, reflecting consumption by circulating immune complexes. Cryoglobulins can be present in malignancy (plasma cell dyscrasias, lymphoma and leukemia), chronic infections (hepatitis B, hepatitis C and endocarditis), inflammatory rheumatic disease (Sjögren's syndrome, SLE and rheumatoid arthritis) or in the syndrome of mixed essential cryoglobulinemia. Mixed essential cryoglobulinemia is now known to be strongly associated with hepatitis C. Cryoglobulins are antibodies that reversibly precipitate in cold. They should be collected in a warmed tube and kept warm on transport to the laboratory. There are two staining patterns for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Cytoplasmic ANCA (C-ANCA) most often represents antibody to proteinase 3 and is present in up to 90 percent of patients with active, diffuse Wegener's granulomatosis and quite specific in the appropriate clinical setting. Perinuclear ANCA (P-ANCA), which is often caused by anti-myeloperoxidase antibody, is less specific but is often present when vasculitis affects small to medium-sized arteries. Arteriography and Biopsy Confirmation of a clinical suspicion of vasculitis usually requires arteriography, biopsy, or both. Evaluation should be directed toward establishing a tissue diagnosis, if possible. In general, because "blind" biopsy of asymptomatic sites or organs generally has a low yield,2 it is best to "go where the money is." For example, if a patient is over age 50 and presents with a new, unexplained headache and elevated ESR, with or without a tender or abnormal temporal artery, a temporal artery biopsy would be indicated. Similarly, in a patient who presents with a multisystem illness and testicular pain and swelling, a testicular biopsy should be considered. Sural nerve biopsy may be indicated in a patient with numbness and tingling in a lower extremity. If the urine sediment is abnormal, a renal biopsy might be obtained. If a biopsy is impractical, an angiogram may be diagnostic. An angiogram should be obtained in cases of suspected large-vessel vasculitis, such as of the branches of the aorta, which may be manifested as extremity ischemia or claudication. A patient with abdominal pain may have mesenteric or renal vasculitis. If visceral involvement is suspected (and in the absence of a surgical abdomen), a visceral angiogram to include the celiac, mesenteric, renal and, perhaps, hepatic arteries should be performed.