Why Violence Has Declined

advertisement

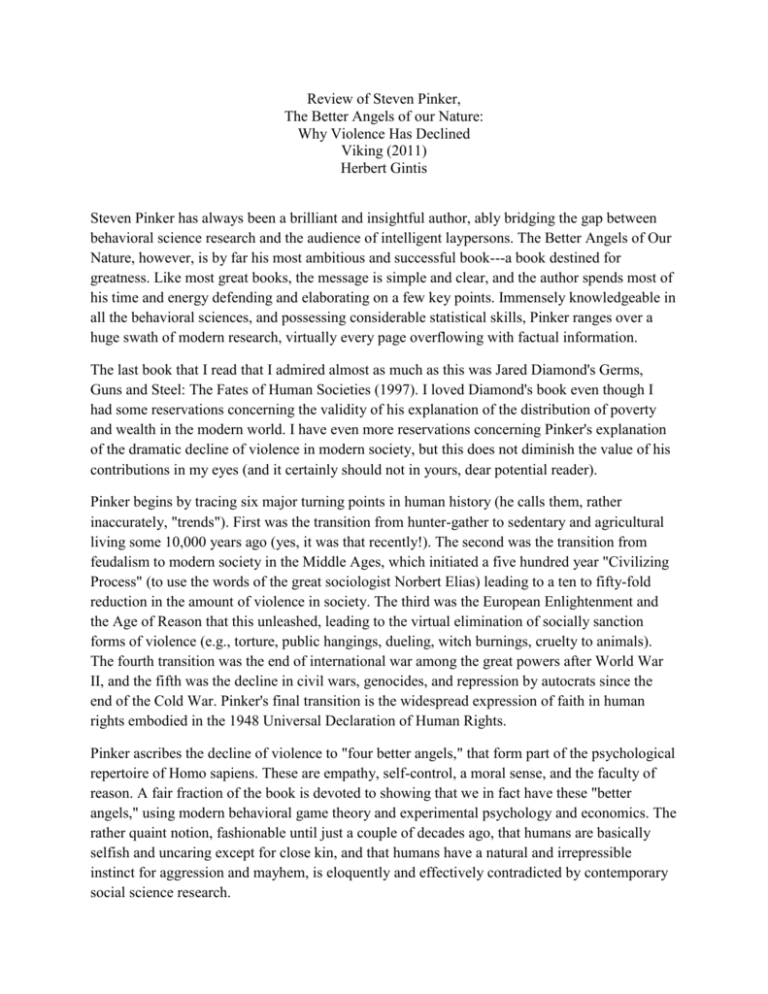

Review of Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Viking (2011) Herbert Gintis Steven Pinker has always been a brilliant and insightful author, ably bridging the gap between behavioral science research and the audience of intelligent laypersons. The Better Angels of Our Nature, however, is by far his most ambitious and successful book---a book destined for greatness. Like most great books, the message is simple and clear, and the author spends most of his time and energy defending and elaborating on a few key points. Immensely knowledgeable in all the behavioral sciences, and possessing considerable statistical skills, Pinker ranges over a huge swath of modern research, virtually every page overflowing with factual information. The last book that I read that I admired almost as much as this was Jared Diamond's Germs, Guns and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (1997). I loved Diamond's book even though I had some reservations concerning the validity of his explanation of the distribution of poverty and wealth in the modern world. I have even more reservations concerning Pinker's explanation of the dramatic decline of violence in modern society, but this does not diminish the value of his contributions in my eyes (and it certainly should not in yours, dear potential reader). Pinker begins by tracing six major turning points in human history (he calls them, rather inaccurately, "trends"). First was the transition from hunter-gather to sedentary and agricultural living some 10,000 years ago (yes, it was that recently!). The second was the transition from feudalism to modern society in the Middle Ages, which initiated a five hundred year "Civilizing Process" (to use the words of the great sociologist Norbert Elias) leading to a ten to fifty-fold reduction in the amount of violence in society. The third was the European Enlightenment and the Age of Reason that this unleashed, leading to the virtual elimination of socially sanction forms of violence (e.g., torture, public hangings, dueling, witch burnings, cruelty to animals). The fourth transition was the end of international war among the great powers after World War II, and the fifth was the decline in civil wars, genocides, and repression by autocrats since the end of the Cold War. Pinker's final transition is the widespread expression of faith in human rights embodied in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Pinker ascribes the decline of violence to "four better angels," that form part of the psychological repertoire of Homo sapiens. These are empathy, self-control, a moral sense, and the faculty of reason. A fair fraction of the book is devoted to showing that we in fact have these "better angels," using modern behavioral game theory and experimental psychology and economics. The rather quaint notion, fashionable until just a couple of decades ago, that humans are basically selfish and uncaring except for close kin, and that humans have a natural and irrepressible instinct for aggression and mayhem, is eloquently and effectively contradicted by contemporary social science research. The better angels of our human nature do not operate, however, in a social vacuum. Rather, Pinker asserts, there are five historical forces that have led to the triumph of empathy, selfcontrol, a moral sense, and the faculty of reason over the equally powerful human thirst to exploit and dominate other groups, and to take revenge against those who have offended us with no sense of self-control, temperance, or forgiveness. The first of these historical forces he calls "Leviathan" (following Hobbes)---the rise of the state and judiciary that enforces a monopoly of coercion, and funnels disputes between individuals and groups through the judicial apparatus. The second is commerce, the globalization of which starting in the sixteen century, which changes international relations into a positive sum game that is crippled by war. The third historical force is feminization, through which the interests and values of women are increasing respected and generalized to both sexes. The fourth is cosmopolitanism, including literacy, mobility, and mass media, which lead people increasingly to understand the mind-sets and desires of others unlike themselves, and to expand their circle of sympathy to larger and larger groupings of individuals. The fifth, says Pinker, is the "escalator of reason," through which people can learn from the past the futility of acting out their primitive urges, and rather turn to peaceful solutions to their problems. Perhaps the most surprising, and welcome, aspect of Pinker's new work is that it is implicitly a devastating nail-in-the-coffin critique of the brand of evolutionary psychology with which Pinker has identified for many years. The brand of evolutionary psychology initiated by Lida Cosmides and John Tooby began with with a high-precision and effective attack on mainstream psychology and sociology, which they called the Standard Social Sciences Model (SSSM). According to the SSSM, the human mind is a blank slate at birth (nota bene: the title of one of Pinker's books was The Blank Slate), and individual psychological characteristics are determined purely by the dominant culture in which the individual is raised. "Human nature," as Karl Marx proclaimed in the Theses on Feuerbach, "is the sum of social relations" (Marxism and mainstream social theory agreed on this central tenet). Thus, in a culture that approves of violence there will be lots of violence, which in a culture that approves of pacific relations, there will be peace. In a society that recognizes differences between the sexes, there will be exhibited exactly those differences so recognized. And so on. The SSSM would be a mixed blessing if it were true. On the one hand, we could engineer culture to produces people who are kind, considerate, and helpful to one another. On the other hand, a totalitarian state could produce people who willingly follow the dictates of Big Brother, inevitably rat on the deviations of their friends and family members from the Socially Desirable Behavior, and live on hay and cider while their masters dined on caviar and Champagne (Yves Montand one sang "Il faut une chasuble d'or pour chanter Beni Createur. Nous en tissons, grands de l'Eglise, et nous, pauvres canuts, n'ont pas de chemises.") However, the SSSM is surely not true, as we have learned from the work of Cosmides and Tooby, followed by a few decades of behavioral economic and psychology. Just a Marx's materialism is Hegel's idealism "stood on its head," so Cosmides and Tooby's evolutionary psychology is the SSSM stood on its head: genes are everything and culture is a palsied epiphenomenon, the instantaneous representation of the human gene pool. However, Pinker's explanation of the remarkable decline in violence that hallmarks human prehistory and history has an explanation in which genes and culture interact in a rather balanced manner (this is called "gene-culture coevolution"). Humans have empathy and a moral sense not because these virtues are impressed upon us as blank slates, but because we evolved in such a manner that those with empathy and a moral sense had more offspring that the sociopaths, and they passed the genes that precondition empathy and morality on to their offspring. Culture is thus not an epiphenomenon that is completely subservient so social structure, but a driving force in the transformation of social structure. The problem with Pinker's argument is that it leaves us with a sense of post hoc propter hoc. Humans became nicer in many different ways at once over the years (the Civilizing Process) and we really cannot say why it came out the way it did. I think Pinker's stress on the role of the state in reducing violence is undoubtedly correct, but why did the growth of state power not lead to the sort of totalitarian despotism that was so feared in the early twentieth century, and so hoped for by the Communists, Nazi, and Fascist states of the world? Why has cosmopolitanism led to the spread of liberating information technologies, rather than highly efficient despotic control of information by an authoritarian state? One could answer that the human drive for freedom and dignity, a legacy from our huntergatherer past, accounts for the control of the means of coercion by the mass of citizens (note that in a fully efficient coercive state, there is no violence at all--although there might be some ineluctable "reeducation")? I think the answer probably lies in the nature technology. The egalitarian nature of simple hunter-gatherer societies was predicated on the existence of lethal weapons, making it impossible, in an age before property, for an individual to control the group through force, because anyone can kill anyone else, catching him by surprise, at low persona cost. With the advent of sedentary and agricultural communities, private property permitted a ruling class to control the masses by force, and primitive egalitarianism was completely eclipsed in the human world. Only with the development of the handgun and bored rifle in the eighteenth and later centuries prevented the hegemony of a ruling class of mounted warriors. The age of democracy was at the same time the age of foot soldiers and the infantrybased army. In thinking about Pinker's argument, I am led to think that he understates the role of information technology in the decline of violence. When my Jewish ancestors were murdered in Polish pogroms, their tormenters were told that Jews sacrificed Christians on their Holy Days, and their unleavened bread was an admixture of wheat and Christian blood. My mother-in-law recounted to me the following story. As a young bride, she took the bus every Saturday to visit her husband where he was stationed. After a couple of weeks, she became friendly with another young bride in the same situation, and thereafter they sat together passing the time talking during the trip. One day my mother-in-law mentioned that she was Jewish. Her friend, completely horrified, pushed her away in disgust, and asked her where her horns were, which her priest had assured her all Jewish women had under the kerchiefs. My point is that now you just can't get away with manipulating people into believing such falsehoods because there is no power so despotic as to be able to shields its people from the truth.