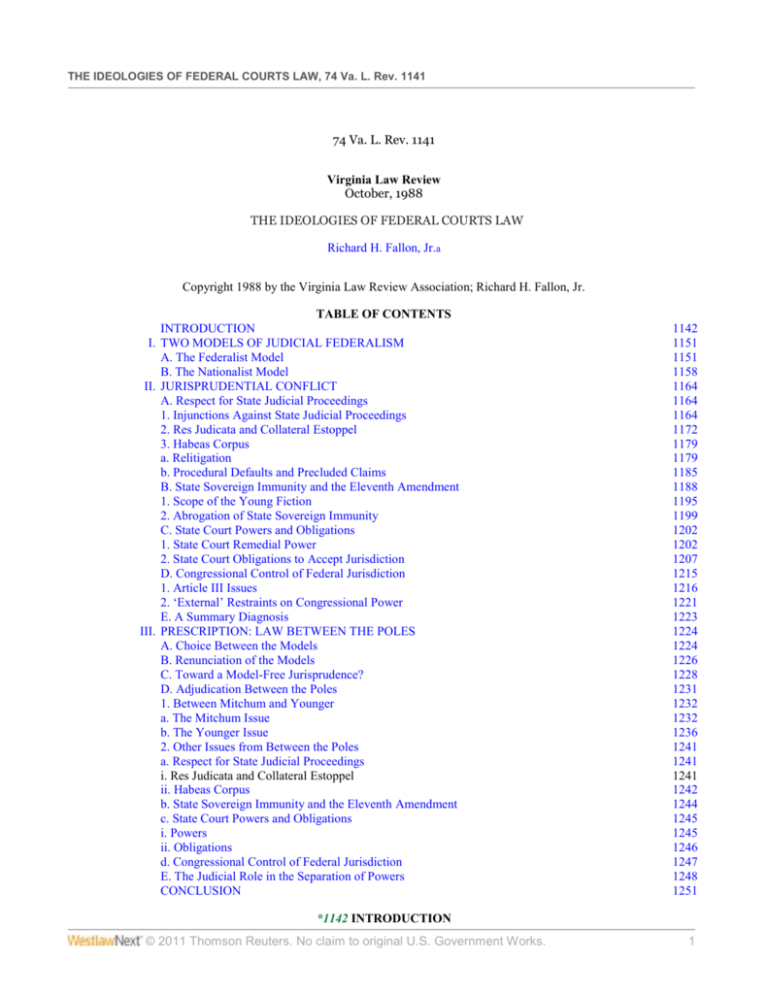

74 Virginia Law Review 1141 The Ideologies of Federal Courts Law

advertisement