Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) S1: Material and methods

advertisement

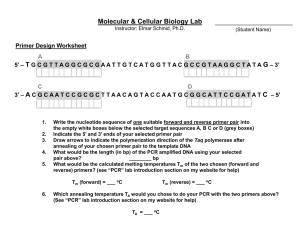

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) S1: Material and methods Eight Eurema mandarina females were captured on Tanegashima Island, Japan, from populations previously reported to be infected with both Wolbachia strains wCI and wFem [1]. These females were kept in isolation for egg-laying. Five females showed a female-only offspring ratio, whereas three had unbiased offspring ratios (ESM S1 Table 1). For the qPCR experiment we used 11 daughters of all-female broods; for unbiased broods we used eight males and eight females. The unbiased broods were either infected with wCI (a total of five females and five males from mothers 6-8) or cured from infection after tetracycline treatment (three females and three males from mother 6). ESM 1 Table 1. Eurema mandarina from Tanegashima and their offspring included in this study Mother Daughters Daughters Sons # n used in qPCR n 1 8 3 - Sons used in qPCR - 2 8 3 - - 3 2 2 - - 4 3 3 - - 5 6 0 - - 6 7 5 6 5 7 1 1 1 1 8 3 2 4 2 As control we included three female and three male E. mandarina from Hachijō-jima Island, Japan, from a population previously found to be infected only by wCI. We also included five females and five males of each wCI infected E. hecabe and uninfected E. smilax from various locations in Australia (ESM S2). DNA isolation Genomic DNA was extracted from single legs (the standard tissue used for Wolbachia detection in E. hecabe [1]) using the GenElute Mammalian Genomic Miniprep kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA was eluted in 100 µL elution solution and then stored at 4 °C. Wolbachia screening PCR PCR-based screening of Eurema individuals was performed using strain specific wsp primers for wCI and wFem [1]. Cycling conditions were 3 min at 94 °C, then 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 60 s, and a final step at 72 °C for 10 min, and the master mix was as listed in ESM 1 Table 2. PCR of the Tpi gene The Tpi gene is located on the Z chromosome of lepidopteran species. We amplified a highly variable intron using primers that were positioned in the conserved exon region of Tpi and previously used in [2]. The PCR cycling conditions were 3 min at 94 °C, then 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 1 min 20 s, and a final step at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were cleaned for direct sequencing by treatment with a combination of 0.5 U Exonuclease I (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and 0.25 U Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (Promega), with incubation at 37°C for 30min, then 95°C for 5min, prior to capillary sequencing by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea). ESM 1 Table 2. PCR conditions for Wolbachia detection and the Tpi gene wsp (wCI, wFem) Tpi 10 µL 20 µL 1x 1x Primer 1 0.4 µM 0.8 µM Primer 2 0.4 µM 0.8 µM 0.5 U 1U 1 µL 1 µL PCR protocol Total volume 5x MyTaq Red Reaction Buffer MyTaq™ Red DNA Polymerase (Bioline) DNA Template Sequence data analysis In total we direct sequenced Tpi from 57 specimens of 8 mothers and their offspring (11 males and 38 females, see ESM S3). No indels or SNPs were observed in sequence chromatograms of females; some males where heterozygous due to detected double peaks and shifts of sequence reads. For this reason we sequenced males form both sides and assigned the ambiguous positions using the IUPAC code. We used PHASE [3] algorithm as implement in DnaSP v5.10.01 [4] to infer putative Tpi alleles (coded as Allele 1 and Allele 2 in ESM S3). The sequences were then trimmed and edited in Geneious version 8.0.4 [5]. The 485 bp alignment consisted of 13 parsimony informative sites, representing 17 haplotypes. The overall haplotype diversity was 0.914. We conducted a network analysis using the median-joining method [6] implemented in PopART [7]. The network (ESM S4) shows the high haplotype diversity. Of the 17 haplotypes only 5 haplotypes were shared between families. There was also no clear divergence of alleles found in wCI and wFem coinfected individuals. We also confirmed the presence of the qPCR primer sequences within individual sequences and thus excluded the presence of any pseudogenes in our sequence alignment. qPCR primer design Tpi primers were designed in an exon region of previously published sequences of E. mandarina (GenBank accession numbers: AB231163-AB231194) [8]. Primers amplifying an exon region of the kettin gene were designed based on an RNAseq sequence of E. mandarina (D Kageyama, personal communication) and sequenced from two females each of E. mandarina, E. hecabe and E. smilax (GenBank accession numbers KM502545-KM502550). Primers for EF-1α were designed from previously published E. mandarina sequences (GenBank accession numbers: AB194749-AB194754). All primers are shown in ESM 1 Table 3 and were designed using the software PrimerQuest (http://www.idtdna.com/SCITOOLS/Applicati ons/PrimerQuest/). ESM 1 Table 3. qPCR primers used for the amplification of Tpi, kettin and Ef-1α Name Primer sequence (5’ 3’) TPI-F GGC CTC AAG GTC ATT GCC TGT TPI-R ACA CGA CCT CCT CGG TTT TAC C Ket-F TCA GTT AAG GCT ATT AAC GCT CTG Ket-R ATA CTA CCT TTT GCG GTT ACT GTC EF-1F AAA TCG GTG GTA TCG GTA CAG TGC EF-1R ACA ACA ATG GTA CCA GGC TTG AGG Tm, primer melting temperature Amplicon length (bp) Tm (℃) 60 73 60 60 73 60 60 73 60 qPCR conditions qPCR reactions were performed on a Rotor-Gene Q PCR system (Qiagen). Using 20 µL reactions, each qPCR reaction contained 1x SensiFAST™ SYBR No-ROX (Bioline), 0.8 µL of each primer and 1 µL of template DNA. Each DNA template was diluted 1:10 prior to reaction set up. Cycling conditions for all qPCR reactions were 2 min at 95 °C, then 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C, 10 s at 60 °C and 10 s at 72 °C. A melt curve for each primer pair was conducted to clarify that there was no primer dimer formation. Every run was performed analysing each specimen in three technical replicates with all three primer sets including a no-template control. One E. mandarina male was selected as a run calibrator in all runs in order to compare runs. Quantitative Analysis of Gene Dose Ratio PCR amplification efficiencies were measured for each individual reaction using LinRegPCR [9] and tested that they were approximately equal [9]. The relative copy number of the Z-linked genes was obtained as gene dose ratio (GDR) using the 2ΔΔCt method, ΔCt = Cttarget - Ctreference [10]. The target and the reference PCR efficiencies where approximately equal with less than 10 % difference and the ratios were calculated without efficiency correction [10]. References [1] Narita S, Kageyama D, Nomura M, Fukatsu T. 2007 Unexpected mechanism of symbiont-induced reversal of insect sex: feminizing Wolbachia continuously acts on the butterfly Eurema hecabe during larval development. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4332-4341. (doi:10.1128/aem.00145-07). [2] Jiggins CD, Linares M, Naisbit RE, Salazar C, Yang ZH, Mallet J. 2001 Sex-linked hybrid sterility in a butterfly. Evolution 55, 1631-1638. (doi:10.1111/j.00143820.2001.tb00682.x). [3] Stephens M, Donnelly P. 2003 A comparison of bayesian methods for haplotype reconstruction from population genotype data. The American Journal of Human Genetics 73, 1162-1169. (doi:10.1086/379378). [4] Librado P, Rozas J. 2009 DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451-1452. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187). [5] Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, et al. 2012 Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647-1649. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199). [6] Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Röhl A. 1999 Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 16, 37-48. [7] http://popart.otago.ac.nz PopArt: Population Analysis with Reticulate Trees. [8] Narita S, Nomura M, Kato Y, Fukatsu T. 2006 Genetic structure of sibling butterfly species affected by Wolbachia infection sweep: evolutionary and biogeographical implications. Molecular Ecology 15, 1095-1108. (doi:10.1111/j.1365294X.2006.02857.x). [9] Ramakers C, Ruijter JM, Deprez RHL, Moorman AFM. 2003 Assumption-free analysis of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) data. Neuroscience Letters 339, 62-66. (doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(02)01423-4). [10] Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001 Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−DDCT method. Methods 25, 402-408. (doi:10.1006/meth.2001.1262).