Lecture Fourteen Postclassical Patterns of Imitation

advertisement

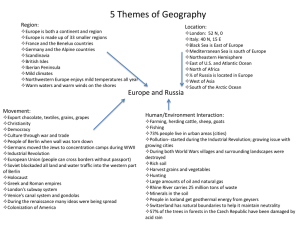

Lecture Fourteen Postclassical Patterns of Imitation Scope: Many societies in which the apparatus of civilization was fairly new used the opportunity provided by contacts with neighboring older societies to copy aspects of culture, technology, and social structure. This is a further illustration of the importance of the new interregional network, though the imitations were on a regional rather than a global level. Japan, Russia, and Western Europe provide examples of the process, which includes other cases, such as Vietnam and Korea in East Asia and the Southeast Asian importation of religious and artistic forms from India, China, and later the Middle East. Imitation helps provide some common themes and comparative opportunities for the otherwise diffuse process of civilization expansion. It also raises questions, however, about civilization definition: Was Japan part of a larger, Chinese-dominated East Asian civilization, or did it remain so different from China that it should be handled separately? How is Russia to be treated in relation to other parts of Christian Europe? Finally, the process of imitation did not extend well to politics, where attempts to copy larger government models largely failed in favor of more decentralized systems. Here, too, is a common dynamic among the imitative societies, though a somewhat negative one. Outline I. In this lecture, we will look at patterns of imitation in Japan, Russia, Southeast Asia, and briefly, Western Europe during the postclassical period. In the process, we will touch on a number of key themes. A. First, we will continue with the theme of interregional contacts, but in these cases, the distances are smaller than those we saw in the last lecture. B. We will also see the continuing spread of civilization. C. Finally, we will see that these regions were different in terms of cultural systems, religions, political systems, and trade patterns, but we will also note a common process of increasing convergence in which societies deliberately undertook activities that would bring them closer to adjacent, more prosperous societies without fully merging with them. II. Early in the postclassical period and continuing for at least a century, Japan organized expeditions to China in search of trade and knowledge. The Japanese came to imitate China in an impressive range of sectors. A. The Japanese learned new agricultural and manufacturing techniques from the Chinese that spurred development of the Japanese economy. B. Japan also took up much of the culture and cultural apparatus of China, including its writing system, basic verse styles, martial arts, the art of gardening, and Buddhism; with Buddhism came architectural forms such as the pagoda and temple. C. Chinese social ideas were adopted in Japan to a limited extent. 1. The prestige of merchants declined slightly in Japan. 2. The Japanese did not import the full range of Chinese thought about gender relations, but they did learn from the Chinese that women were less equal to men than the Japanese had previously believed. D. Japan adopted something of China’s superior attitude toward the wider world. E. One reason that the Japanese did not attempt a larger expansion effort in this period may be that their horizons were limited by the idea that they had nothing to learn from places other than China. III. Trade ran through western Russia and the Ukraine during the postclassical period, connecting Russia with the Byzantine Empire. A. Russians traveled to Constantinople for political missions and cultural exchange, and Byzantine emissaries were active in Russia. B. The Russians got their writing system and religion from the Byzantine Empire. C. Along with religion and writing came a larger cultural apparatus conditioned by the extent to which Russia was a less prosperous, less sophisticated society than Byzantium. Byzantine architectural styles were imitated, along with the Byzantine tradition of iconography. D. From the Byzantines, Russian leaders incorporated at least some sense of political horizons. A kind of historical chain was believed to link Rome to Byzantium to Russia. IV. Japan and Russia exhibited similarities in the basic process of adoption and adaptation. A. In each instance, people in the imitating society believed that there was a positive advantage in visiting and copying aspects of the adjacent, more prosperous society. B. This process raises a question that is crucial for the postclassical period: now that civilization is expanding and societies are deliberately imitating each other, how do we define a civilization? 1. In the Japanese case, Japan imitated China, but it did not become Chinese. 2. The efficiency of identifying an East Asian civilization zone probably outweighs the drawbacks, but the label is clearly an oversimplification. 3. We can view Russia as a partial heir to a Byzantine/East European tradition that distinguishes it from Western Europe; thus, we have two major civilization zones in Europe: the West and the East- Central East. V. In the postclassical period, a number of regional kingdoms emerged in Southeast Asia. At the same time, this region received significant cultural and commercial influence from other sources, notably, India. A. Indian traders sometimes brought Hinduism into this region, and the spread of Buddhism from India was even more striking. From India also came inspiration for regional writing systems. B. Chinese influence is seen here, particularly in the form of increasing trade activity from the time of the Song dynasty onward. C. By the end of the postclassical period, Islam had gained the greatest religious success in many parts of this region. D. This pattern of varying outside influences combined with local traditions sets up a different model in Southeast Asia from that seen in Japan and Russia. VI. Western Europe did not have the same needs that Japan and Russia did from its influences, but West European leaders saw clear advantages in imitating certain aspects of the Byzantine Empire and the Arab world. A. Western Europe used these contacts to regain knowledge of classical learning that had been preserved by the Byzantines and Arabs. B. From the Muslims and the Byzantines, Western Europeans also copied a variety of technologies and benefited from Arab advances in medicine, mathematics, and other fields. C. The Arab philosophical debate over the boundaries between faith and reason was transmitted to Europe, where it was applied to Christian interests in rationalism. D. The Gothic arch—that quintessential artistic symbol of postclassical Western Europe— was, in part, adapted from the characteristic Islamic arch. E. Western Europe borrowed from Islamic innovations in commercial law, identifying principles that could transcend political boundaries and protect merchants regardless of specific location. F. Whether acknowledged or not, the Western European debt to Islamic and Byzantine examples was considerable. The fact that this period was one of extensive imitation is an important addition to our understanding of postclassical Western Europe. VII. The imitation process raises one final question for the period itself and carries some interesting implications for more contemporary situations. A. In all four cases, cultural forms and styles, along with technologies, seem to have been particularly eagerly sought. Why is this so? B. One fact that prompts this question is the lack of success with the imitation of political forms. 1. Japan, Russia, and Western Europe were aware that political models existed that were superior to their own decentralized situations. As Japan began to imitate China, for example, it exhibited a deliberate desire to import the Chinese imperial system. 2. For almost a century, the Chinese example was incorporated into Japanese political activity, but the effort failed because Japan could not sustain the same degree of centralization as China. 3. The Japanese solution, during the bulk of the postclassical period, would be a form of feudalism. C. Russian leaders were aware of Byzantine political examples, but they did not wield the same power and could not establish a tightly organized political system. D. The Western Europeans had a chance to establish a more centralized political structure under Charlemagne in the early-9th century. 1. Charlemagne’s realm extended to northern Italy, very northern Spain, France, the Low Countries, and parts of western Germany. 2. Charlemagne, however, lacked the resources and, possibly, the experience to set up an independent bureaucracy. 3. Charlemagne ended up reinforcing Western European feudalism. E. We see here societies that are capable of imitating models to speed up artistic, literary, and cultural development, but are the imitators inherently less able to use political examples? 1. Is a period of cultural gestation necessary before a society can imitate another society’s political achievements, and if so, does this characteristic still apply in the world today? 2. We have a number of instances today in which societies seek or are told to seek political inspiration from countries that have different political experience. Are such models particularly difficult to follow, or is the political delay we have noted confined to the postclassical period? VIII. The postclassical period saw a great deal of deliberate imitation and a substantial degree of success in this arena. A. Connections were forged between societies that were new to the civilization phenomenon and those in which civilization patterns were better established, but these connections never completely erased issues of definition between such civilizations as Russia and Byzantium or Japan and China. B. B. In three of the major cases—Japan, Russia, and Western Europe—the societies involved were on the peripheries of the most sophisticated patterns available during the postclassical period. These three societies would use this period of imitation as gestation for a later, stronger, emergence in world history.