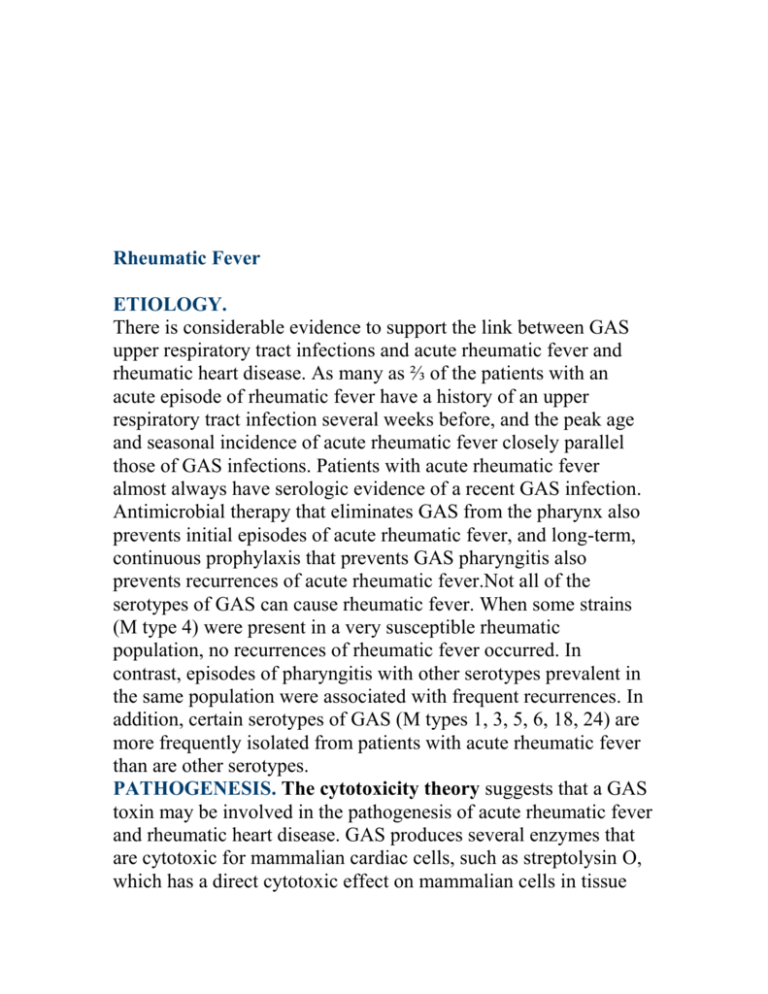

Chemoprophylaxis for Recurrences of Acute Rheumatic Fever

advertisement

Rheumatic Fever ETIOLOGY. There is considerable evidence to support the link between GAS upper respiratory tract infections and acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. As many as ⅔ of the patients with an acute episode of rheumatic fever have a history of an upper respiratory tract infection several weeks before, and the peak age and seasonal incidence of acute rheumatic fever closely parallel those of GAS infections. Patients with acute rheumatic fever almost always have serologic evidence of a recent GAS infection. Antimicrobial therapy that eliminates GAS from the pharynx also prevents initial episodes of acute rheumatic fever, and long-term, continuous prophylaxis that prevents GAS pharyngitis also prevents recurrences of acute rheumatic fever.Not all of the serotypes of GAS can cause rheumatic fever. When some strains (M type 4) were present in a very susceptible rheumatic population, no recurrences of rheumatic fever occurred. In contrast, episodes of pharyngitis with other serotypes prevalent in the same population were associated with frequent recurrences. In addition, certain serotypes of GAS (M types 1, 3, 5, 6, 18, 24) are more frequently isolated from patients with acute rheumatic fever than are other serotypes. PATHOGENESIS. The cytotoxicity theory suggests that a GAS toxin may be involved in the pathogenesis of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. GAS produces several enzymes that are cytotoxic for mammalian cardiac cells, such as streptolysin O, which has a direct cytotoxic effect on mammalian cells in tissue culture. An immune-mediated pathogenesis for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease has been suggested by the clinical similarity of acute rheumatic fever to other illnesses produced by immunopathogenic processes and by the latent period between the GAS infection and the acute rheumatic fever. The antigenicity of a large variety of GAS products and constituents, as well as the immunologic cross reactivity between GAS components and mammalian tissues, also lends support to this hypothesis. Common antigenic determinants are shared between certain components of GAS (M protein, protoplast membrane, cell wall group A carbohydrate, capsular hyaluronate) and specific mammalian tissues (e.g., heart, brain, joint). CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSIS. Because no clinical or laboratory finding is pathognomonic for acute rheumatic fever, T. Duckett Jones in 1944 proposed guidelines to aid in diagnosis and to limit overdiagnosis. The Jones criteria, as revised in 1992 by the American Heart Association are intended only for the diagnosis of the initial attack of acute rheumatic fever and not for recurrences. There are 5 major and 4 minor criteria and an absolute requirement for evidence (microbiologic or serologic) of recent GAS infection. The diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever can be established by the Jones criteria when a patient fulfills 2 major criteria or 1 major and 2 minor criteria and meets the absolute requirement. There are 3 circumstances in which the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever can be made without strict adherence to the Jones criteria. Chorea may occur as the only manifestation of acute rheumatic fever. Similarly, indolent carditis may be the only manifestation in patients who 1st come to medical attention months after the onset of acute rheumatic fever. Finally, although most patients with recurrences of acute rheumatic fever fulfill the Jones criteria, some may not. Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Initial Attack of Rheumatic Fever (Jones Criteria, Updated 1992) SUPPORTING EVIDENCE OF ANTECEDENT MAJOR MINOR GROUP A MANIFESTATIONS MANIFESTATION STREPTOCOCCA [*] S L INFECTION Carditis Positive throat Clinical features: culture or rapid streptococcal antigen test Polyarthritis Arthralgia Fever Elevated or increasing streptococcal antibody titer Erythema marginatum Laboratory features: Subcutaneous nodules Elevated acute phase reactants: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate C-reactive protein Prolonged PR interval Chorea MIGRATORY POLYARTHRITIS. Arthritis occurs in about 75% of patients with acute rheumatic fever and typically involves larger joints, particularly the knees, ankles, wrists, and elbows. Involvement of the spine, small joints of the hands and feet, or hips is uncommon. Rheumatic joints are generally hot, red, swollen, and exquisitely tender; even the friction of bedclothes is uncomfortable. The pain can precede and can appear to be disproportionate to the other findings. The joint involvement is characteristically migratory in nature; a severely inflamed joint can become normal within 1–3 days without treatment, as 1 or more other large joints become involved. Severe arthritis can persist for several weeks in untreated patients. Monoarticular arthritis is unusual unless anti-inflammatory therapy is initiated prematurely, aborting the progression of the migratory polyarthritis. If a child with fever and arthritis is suspected of having acute rheumatic fever, it frequently is useful to withhold salicylates and observe for migratory progression. A dramatic response to even small doses of salicylates is another characteristic feature of the arthritis, and the absence of such a response should suggest an alternative diagnosis. Rheumatic arthritis is typically not deforming. Synovial fluid in acute rheumatic fever usually has 10,000–100,000 white blood cells/mm3 with a predominance of neutrophils, a protein of about 4 g/dL, a normal glucose, and forms a good mucin clot. Frequently, arthritis is the earliest manifestation of acute rheumatic fever and may correlate temporally with peak antistreptococcal antibody titers. There is an apparent inverse relationship between the severity of arthritis and the severity of cardiac involvement. CARDITIS. Carditis and resultant chronic rheumatic heart disease are the most serious manifestations of acute rheumatic fever and account for essentially all of the associated morbidity and mortality. Rheumatic carditis is characterized by pancarditis, with active inflammation of myocardium, pericardium, and endocardium. Cardiac involvement during acute rheumatic fever varies in severity from fulminant, potentially fatal exudative pancarditis to mild, transient cardiac involvement. Endocarditis (valvulitis), which manifests by 1 or more cardiac murmurs, is a universal finding in rheumatic carditis, whereas the presence of pericarditis or myocarditis is variable. Myocarditis and/or pericarditis without evidence of endocarditis is rarely due to rheumatic heart disease. Most cases consist of either isolated mitral valvular disease or combined aortic and mitral valvular disease. Isolated aortic or right-sided valvular involvement is uncommon. Serious and longterm illness is related entirely to valvular heart disease as a consequence of a single attack or recurrent attacks of acute rheumatic fever. Valvular insufficiency is characteristic of both acute and convalescent stages of acute rheumatic fever, whereas valvular stenosis usually appears several years or even decades after the acute illness. In developing countries, however, where acute rheumatic fever often occurs at a younger age, mitral stenosis and aortic stenosis may develop sooner after acute rheumatic fever than in developed countries, and can occur in young children. Acute rheumatic carditis usually presents as tachycardia and cardiac murmurs, with or without evidence of myocardial or pericardial involvement. Moderate to severe rheumatic carditis can result in cardiomegaly and congestive heart failure with hepatomegaly and peripheral and pulmonary edema. Echocardiographic findings include pericardial effusion, decreased ventricular contractility, and aortic and/or mitral regurgitation. Mitral regurgitation is characterized by a high-pitched apical holosystolic murmur radiating to the axilla. In patients with significant mitral regurgitation, this may be associated with an apical mid-diastolic murmur of relative mitral stenosis. Aortic insufficiency is characterized by a high-pitched decrescendo diastolic murmur at the upper left sternal border. Carditis occurs in about 50–60% of all cases of acute rheumatic fever. Recurrent attacks of acute rheumatic fever in patients who had carditis with the initial attack are associated with high rates of carditis. The major consequence of acute rheumatic carditis is chronic, progressive valvular disease, particularly valvular stenosis, which can require valve replacement and predispose to infective endocarditis. CHOREA. Sydenham chorea occurs in about 10–15% of patients with acute rheumatic fever and usually presents as an isolated, frequently subtle, neurologic behavior disorder. Emotional lability, incoordination, poor school performance, uncontrollable movements, and facial grimacing, exacerbated by stress and disappearing with sleep, are characteristic. Chorea occasionally is unilateral. The latent period from acute GAS infection to chorea is usually longer than for arthritis or carditis and can be months. Onset can be insidious, with symptoms being present for several months before recognition. Clinical maneuvers to elicit features of chorea include (1) demonstration of milkmaid's grip (irregular contractions of the muscles of the hands while squeezing the examiner's fingers), (2) spooning and pronation of the hands when the patient's arms are extended, (3) wormian darting movements of the tongue upon protrusion, and (4) examination of handwriting to evaluate fine motor movements. Diagnosis is based on clinical findings with supportive evidence of GAS antibodies. However, in patients with a long latent period from the inciting streptococcal infection, antibody levels may have declined to normal. Although the acute illness is distressing, chorea rarely, if ever, leads to permanent neurologic sequelae. ERYTHEMA MARGINATUM. Erythema marginatum is a rare (<3% of patients with acute rheumatic fever) but characteristic rash of acute rheumatic fever. It consists of erythematous, serpiginous, macular lesions with pale centers that are not pruritic. It occurs primarily on the trunk and extremities, but not on the face, and it can be accentuated by warming the skin. SUBCUTANEOUS NODULES. Subcutaneous nodules are a rare (≤1% of patients with acute rheumatic fever) and consist of firm nodules approximately 1 cm in diameter along the extensor surfaces of tendons near bony prominences. There is a correlation between the presence of these nodules and significant rheumatic heart disease. Minor Manifestations. The 2 clinical minor manifestations are arthralgia (in the absence of polyarthritis as a major criterion) and fever (typically temperature ≥102°F and occurring early in the course of illness). The 2 laboratory minor manifestations are elevated acute-phase reactants (e.g., C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and prolonged PR interval on electrocardiogram (1st degree heart block). However, a prolonged PR interval alone does not constitute evidence of carditis or predict long-term cardiac sequelae. Recent Group A Streptococcus Infection. An absolute requirement for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever is supporting evidence of a recent GAS infection. Acute rheumatic fever typically develops 2–4 wk after an acute episode of GAS pharyngitis at a time when clinical findings of pharyngitis are no longer present and when only 10–20% of the throat culture or rapid streptococcal antigen test results are positive. One third of patients have no history of an antecedent pharyngitis. Therefore, evidence of an antecedent GAS infection is usually based on elevated or increasing serum antistreptococcal antibody titers. A slide agglutination test (Streptozyme) has been introduced, and it is purported to detect antibodies against 5 different GAS antigens. Although this test is rapid, relatively simple to perform, and widely available, it is less standardized and less reproducible than other tests and should not be used as a diagnostic test for evidence of an antecedent GAS infection. If only a single antibody is measured (usually antistreptolysin O), only 80–85% of patients with acute rheumatic fever have an elevated titer; however, 95–100% have an elevation if 3 different antibodies (antistreptolysin O, anti-DNase B, antihyaluronidase) are measured. Therefore, when acute rheumatic fever is suspected clinically, multiple antibody tests are performed. Except for patients with chorea, clinical findings of acute rheumatic fever generally coincide with peak antistreptococcal antibody responses. Most patients with chorea have elevation of antibodies to 1 or more GAS antigens, although these antibodies may be waning. The diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever should not be made in patients with elevated or increasing streptococcal antibody titers who do not fulfill the Jones criteria because such titer changes may be coincidental. This is most often true in younger, school-aged children, many of whom have GAS pyoderma in the summer or unrelated GAS pharyngitis during the winter and spring months. Differential Diagnosis. . Differential Diagnosis of Acute Rheumatic Fever ARTHRITIS CARDITIS CHOREA Rheumatoid arthritis Viral Huntington chorea myocarditis Reactive arthritis (e.g., Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia) Viral pericarditis Wilson disease Serum sickness Infective endocarditis Systemic lupus erythematosus Sickle cell disease Kawasaki disease Cerebral palsy Malignancy Congenital heart disease Tics Systemic lupus erythematosus Mitral valve prolapse Hyperactivity ARTHRITIS Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) CARDITIS Innocent murmurs CHOREA Gonococcal infection (Neisseria gonorrhoeae) TREATMENT. All patients with acute rheumatic fever should be placed on bed rest and monitored closely for evidence of carditis. They can be allowed to ambulate as soon as the signs of acute inflammation have subsided. However, patients with carditis require longer periods of bed rest. Antibiotic Therapy. Once the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever has been established and regardless of the throat culture results, the patient should receive 10 days of orally administered penicillin or erythromycin, or a single intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin to eradicate GAS from the upper respiratory tract. After this initial course of antibiotic therapy, the patient should be started on longterm antibiotic prophylaxis. Anti-Inflammatory Therapy. Anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., salicylates, corticosteroids) should be withheld if arthralgia or atypical arthritis is the only clinical manifestation of presumed acute rheumatic fever. Premature treatment with 1 of these agents may interfere with the development of the characteristic migratory polyarthritis and thus obscure the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever. Agents such as acetaminophen can be used to control pain and fever while the patient is being observed for more definite signs of acute rheumatic fever or for evidence of another disease. Patients with typical migratory polyarthritis and those with carditis without cardiomegaly or congestive heart failure should be treated with oral salicylates. The usual dose of aspirin is 100 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses PO for 3–5 days, followed by 75 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses PO for 4 wk. Determination of the serum salicylate level is not necessary unless the arthritis does not respond or signs of salicylate toxicity (tinnitus, hyperventilation) develop. There is no evidence that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are any more effective than salicylates. Patients with carditis and cardiomegaly or congestive heart failure should receive corticosteroids. The usual dose of prednisone is 2 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses for 2–3 wk followed by a tapering of the dose that reduces the dose by 5 mg/24 hr every 2–3 days. At the beginning of the tapering of the prednisone dose, aspirin should be started at 75 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses for 6 wk. Supportive therapies for patients with moderate to severe carditis include digoxin, fluid and salt restriction, diuretics, and oxygen. The cardiac toxicity of digoxin is enhanced with myocarditis. Sydenham Chorea. Because chorea often occurs as an isolated manifestation after the resolution of the acute phase of the disease, anti-inflammatory agents are usually not indicated. Sedatives may be helpful early in the course of chorea; phenobarbital (16–32 mg every 6–8 hr PO) is the drug of choice. If phenobarbital is ineffective, then haloperidol (0.01–0.03 mg/kg/24 hr divided bid PO) or chlorpromazine (0.5 mg/kg every 4–6 hr PO) should be initiated. COMPLICATIONS. The arthritis and chorea of acute rheumatic fever resolve completely without sequelae. Therefore, the long-term sequelae of rheumatic fever are usually limited to the heart Patients with cardiac valvular disease secondary to acute rheumatic fever are at increased risk for developing infective endocarditis during episodes of transient bacteremia. The antibiotic regimens used to prevent recurrences of acute rheumatic fever are inadequate for protection against infective endocarditis. The current recommendations of the American Heart Association regarding infective endocarditis prophylaxis should be followed). Patients with residual rheumatic valvular disease do not always require endocarditis prophylaxis. The importance of good dental hygiene in the prevention of infective endocarditis should also be stressed. Patients who have had rheumatic fever but have no evidence of residual valvular disease do not require endocarditis prophylaxis. PROGNOSIS. The prognosis for patients with acute rheumatic fever depends on the clinical manifestations present at the time of the initial episode, the severity of the initial episode, and the presence of recurrences. Approximately 70% of the patients with carditis during the initial episode of acute rheumatic fever recover with no residual heart disease; the more severe the initial cardiac involvement, the greater the risk for residual heart disease. Patients without carditis during the initial episode are unlikely to have carditis with recurrences. In contrast, patients with carditis during the initial episode are likely to have carditis with recurrences, and the risk for permanent heart damage increases with each recurrence. Patients who have had acute rheumatic fever are susceptible to recurrent attacks following reinfection of the upper respiratory tract with GAS. Therefore, these patients require long-term continuous chemoprophylaxis. Before antibiotic prophylaxis was available, 75% of patients who had an initial episode of acute rheumatic fever had 1 or more recurrences during their lifetime. These recurrences were a major source of morbidity and mortality. The risk of recurrence is highest immediately after the initial episode and decreases with time. Approximately 20% of patients who present with “pure” chorea who are not given secondary prophylaxis develop rheumatic heart disease within 20 yr. Therefore, patients with chorea, even in the absence of other manifestations of rheumatic fever, require longterm antibiotic prophylaxis. PREVENTION. Prevention of both initial and recurrent episodes of acute rheumatic fever depends on controlling GAS infections of the upper respiratory tract. Prevention of initial attacks (primary prevention) depends on identification and eradication of the GAS that produces episodes of acute pharyngitis. Individuals who have already suffered an attack of acute rheumatic fever are particularly susceptible to recurrences of rheumatic fever with any subsequent GAS upper respiratory tract infection, whether or not they are symptomatic. Therefore, these patients should receive continuous antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent recurrences (secondary prevention). Primary Prevention. Appropriate antibiotic therapy instituted before the 9th day of symptoms of acute GAS pharyngitis is highly effective in preventing 1st attacks of acute rheumatic fever from that episode. However, about ⅓ of patients with acute rheumatic fever do not recall a preceding episode of pharyngitis. Secondary Prevention. Secondary prevention is directed at preventing acute GAS pharyngitis in patients at substantial risk of recurrent acute rheumatic fever. Secondary prevention requires continuous antibiotic prophylaxis, which should begin as soon as the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever has been made and immediately after a full course of antibiotic therapy has been completed. Because patients who have had carditis with their initial episode of acute rheumatic fever are at a relatively high risk for having carditis with recurrences and for sustaining additional cardiac damage, they should receive antibiotic prophylaxis well into adulthood and perhaps for life.Patients who did not have carditis with their initial episode of acute rheumatic fever have a relatively low risk for carditis with recurrences. Antibiotic prophylaxis may be discontinued in these patients when they reach their early 20s and after at least 5 yr have elapsed since their last episode of acute rheumatic fever. The regimen of choice for secondary prevention is a single intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin G (1.2 million IU) every 4 wk. In compliant patients, continuous oral antimicrobial prophylaxis can be used. Penicillin V given twice daily and sulfadiazine given once daily are equally effective when used in such patients. For the exceptional patient who is allergic to both penicillin and sulfonamides, erythromycin given twice daily may be used. The duration of secondary prophylaxis is noted in Table. -- Chemoprophylaxis for Recurrences of Acute Rheumatic Fever DRUG DOSE ROUTE Penicillin G 1.2 million U, every 4 wk[*] Intramuscular benzathine OR Penicillin V 250 mg, twice a day Oral 0.5 g, once a day for patients ≤27 kg (≤60 lb) Oral OR Sulfadiazine or sulfisoxazole DRUG DOSE 1.0 g, once a day for patients >27 kg (>60 lb) ROUTE FOR PEOPLE WHO ARE ALLERGIC TO PENICILLIN AND SULFONAMIDE DRUGS Erythromycin 250 mg, twice a day Oral Duration of Prophylaxis for People Who Have Had Acute Rheumatic Fever: Recommendations of the American Heart Association CATEGORY DURATION Rheumatic fever without 5 yr or until 21 yr of age, carditis whichever is longer Rheumatic fever with carditis but without residual heart disease (no valvular disease[*]) 10 yr or well into adulthood, whichever is longer Rheumatic fever with carditis and residual heart disease (persistent valvular disease[*]) At least 10 yr since last episode and at least until 40 yr of age; sometimes lifelong prophylaxis