Examples of Teaching Higher-order Concepts

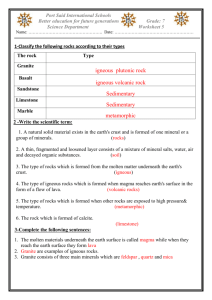

advertisement

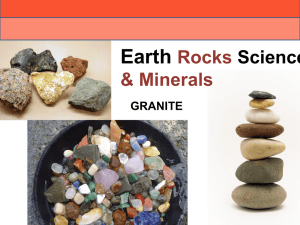

Procedure for Teaching Higher-order (abstract) Concepts: [Needs verbal definition and then examples and nonexamples] Systematic, Explicit, Focused, Direct Instruction First, you need to know about verbal definitions. Genus and difference. Here’s the VERBAL definition of the higher-order concept—constitutional republic. A constitutional republic is a state where the head of state and other officials are representatives of the people and must govern according to existing constitutional law that limits the government's power over citizens. The definition has two parts: genus and difference. Genus. A constitutional republic is a STATE (a political relationship between government and citizens). The genus is the larger category or concept in which constitutional republic in located. The genus tells you what KIND of thing something is and what KINDS of things it isn’t. A constitutional republic is not a society. Not a geographic thing, like mountains. And not anything that other species do. However, constitutional republics are not the only kind of (not the only member of the class of) states. Other kinds of states are monarchies, democracies, and aristocracies. So a full definition has to tell the difference between constitutional republic states and other kinds of states. This is the difference part of a verbal definition. Difference. …. where the head of state and other officials are representatives of the people and must govern according to existing constitutional law that limits the government's power over citizens. The difference part of the definition tells the difference between constitutional republics (as ONE example of state) and OTHER kids of states, such as monarchies, democracies, and aristocracies. A diagram of the verbal definition looks like this. Political states Constitutional republics Monarchies Aristocracies Democracies Note: There is no such thing as a true definition. Rather, some definitions are better than other definitions; they are better at directing attention to the right events. So, definitions are better when: 1. They state the genus and the difference. 2. The difference part of the definition contains enough descriptors (features of the thing defined) that it can easily be distinguished from other kinds of things in the class (genus). Here’s a poor definition. Dogs are canines (genus) with four legs (difference). The genus part is okay. Dogs ARE in the class of canines---along with wolves, foxes, and coyotes. But the difference part is so skimpy that you can’t USE this definition to distinguish dogs (as canines) and foxes, wolves, and coyotes (as canines) because all of them have four legs. Here’s another poor definition. Monarchy is a form of government (genus) in which one person rules (difference). Yes, monarchy IS a form of government (or state) in which one person rules, but the difference (one person rules) does not tell enough to distinguish monarchies and other forms of government in which one person rules. Dictatorships are also rule by one person. So, if a student reads about a dictatorship, the student might WRONGLY judge it to be a monarchy. So, the difference portion should include more features of monarchies (in contrast to dictatorships). Here’s a more descriptive definition. A monarchy is a form of government (genus) in which supreme power is absolutely or nominally lodged with an individual, who is the head virtue of hereditary ascension], often for life or until of state [by abdication…The person who heads a monarchy is called a monarch (difference). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monarchy Now look at a good definition of dictatorship. It is good because it is useful--it enables you to distinguish monarchy (rule by one person) from dictatorship (also rule by one person). A dictatorship is defined as an autocratic [one ruler. MK] form of government in which the government [means the same as “supreme power is absolutely or nominally lodged with an individual”] is ruled by an individual, the dictator, without hereditary ascension. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dictatorship 3. All of the terms have clear meaning; that is, the words in the definition clearly point to the events named. Poor definitions. A donut is a kind of pastry that is shaped like a donut. [Yes, but what is a donut shaped like?] Fear is an emotion that involves being afraid. [Fear and afraid same thing. So, the definition is just saying Fear is an emotion at involves fear.] Procedure for Teaching Concepts: Higher-order [Needs verbal definition and THEN examples/nonexamples] Systematic, Explicit, Focused, Direct Instruction Simile Set up 1. Objective mean the The teacher presents examples and nonexamples of simile and asks, “Is this a simile?” When students answer, the teacher asks, “How do you know?” Student correctly identify similes and nonsimiles, and use the definition to explain their answer. 2. Frame. Teacher. “New figure of speech. Simile. [writes on board or refers to guided notes.] Spell simile.” Class. “s i m i l e .” Teacher. “What word?” Class. “Simile.” Teacher. “Write it in your notebooks, or guided notes.” [Check to make sure they do this.] Focused Instruction 3. Model—lead—test/check. Teacher. “Listen. A simile is a figure of speech in which two unlike things are compared, using the words like or as.” [Model] Teacher. “Listen again. A simile is a figure of speech in which two unlike are compared, using the words like or as.” [Model] Teacher/ “Say it with me. A simile is a figure of speech in which two Students unlike things are compared, using the words like or as. [Lead] Teacher. “Your turn. Define simile.” [Test/check] Students. A simile is a figure of speech in which two unlike things are compared, using the words like or as. Teacher. “Yes, you said that perfectly!” [Verification] Teacher. [Students know the verbal definition. Now the teacher uses examples and nonexamples to display the defining features of the concept that are IN the examples and NOT in the nonexamples.] “Listen. The air was hot as a stove. The air was hot as a stove. Are two things compared?” [The teacher focuses on the details of the definition.] Students. “Yes.” Teacher. “What two things?” Students. “Air and stove.” Teacher. “Is like or as used to compare them?” [Another detail of the definition.] Students. “Yes.” Teacher. “So, is The air was hot as a stove a simile?” [Students use the definition to judge an possible example.] Students. “Yes.” Teacher. “Yes, The air was hot as a stove a simile?” [Verification] [Next, the teacher does exactly the same thing with a second example to firm up the features of the definition and students’ use of the definition to judge a possible example.] [Now the teacher presents a NONexample so that students (comparing the two previous examples with the nonexample) can see the comparison of unlike things, using like or as— difference---the between the examples and the nonexample.] Teacher. “Listen. The evening sun was red ruby. The evening sun was red ruby.” Teacher. “Are two things compared?” Students. “Yes.” Teacher. “What two things.” Students. “Evening sun and red ruby.” Teacher. “Is like or as used to compare them?” Students. “No.” “It said the evening sun WAS red ruby.” Teacher. “So, it compares unlike things, but it does NOT use like or as. So, is it a simile?” Students. “No.” Teacher. “Correct. It is NOT a simile. A simile compares unlike objects AND uses like or as.” [Restates the definition to firm it.] [The teacher then juxtaposes a few more examples and nonexamples the SAME WORDING as above.] 5. Error correction. The teacher corrects errors immediately. For example. Teacher. “Her eyes shined like diamonds. Simile?” Students. A few students say No. Teacher. “Her eyes shined like diamonds. Dos it compare two things?” [Uses the definition to help students make the judgment.] Students. “Yes.” Teacher. “What two things?” Students. “Her hair and diamonds.” Teacher. “Does it use LIKE or as?” [Uses the definition to help students make the judgment.] Students. “Yes.” Teacher. “So, is it a simile?” [Has students make the judgment.] Students. “Yup!” Teacher. “Yup, it IS a simile.” [Verification] [The teacher will return to this example later, to retest.] 6. Delayed acquisition test. The teacher tests all the examples and nonexamples used. Teacher. “The air was hot as a stove. Simile or not simile?” Students. “Simile.” Teacher. “How do you know?” [This requires students to use the definition to judge examples and nonexamples.] using Students. “Compares unlike things.” “Two unlike things.” Air and hot stove.” “Uses as.” Teacher. “Correct!! A class full of geniuses!!” Procedure for Teaching Concepts: Higher-order [Needs verbal definition and THEN examples/nonexamples] Systematic, Explicit, Focused, Direct Instruction Granite Here’s another example of teaching higher-order concepts. Notice that the instruction is highly scaffolded---the teacher does a LOT to make sure that students are firm on the preskills (things they have to know to learn the new stuff), that many examples are used, and that students are getting (figuring out, inducing) the concept. Do you have to teach everything this way—so thoroughly? Well, how do you think they do it in medical school? Do you think the professor makes sure that med students know exactly what different kinds of cancer cells look like? Why? Rule: If it’s important that students learn it, then teach it this way. Objective for acquisition. (1) The teacher presents examples and nonexamples of granite. Students correctly identify 9 out of 10, each within 10 seconds. (2) Students correctly answer the follow-up question (“How do you know?”) 9 out of 10 times, each within 10 seconds. 1. Firm pre-skills Teacher. “We’ve been studying igneous rocks. Here’s our definition. Igneous rocks form from the crystallization of minerals in magma.” “Everyone, say that definition of igneous rocks.” [Check] Class. “Igneous rocks form from the crystallization of minerals in magma.”.] Teacher. “Yes, igneous rocks form from the crystallization of minerals in magma.” [Verification] 2. Frame Instruction Teacher. “Today we’ll examine an igneous rock called granite. Everybody, if granite is an igneous rock, what else do you know about it? Think….” Class. “It forms from the crystallization of minerals in magma.” [Teacher asked students to make a deduction about granite from the definition of igneous rocks. This helps firm their knowledge of the definition, and prepares students to USE of the definition to examine rock samples. “Hmmmm. Is this igneous? No. Then it can’t be granite.”] Teacher. 3. “Excellent deduction!!” Focused Instruction: Model—lead—test/check---verification First the teacher teaches the verbal definition of granite. Teacher. “Here’s the definition of granite. Get ready to write the definition on your note cards.” [Check to see if they are ready.] “Granite is an igneous rock consisting primarily of the minerals quartz, feldspar, and mica. Again, granite is an igneous rock consisting primarily of the minerals quartz, feldspar, and mica.” [Model] “Say it with me.” [Lead] Teacher/ “Granite is an igneous rock consisting of the Class. minerals quartz, feldspar, and mica. [The teacher probably could have left out the lead.] Teacher. “All by yourselves.” [Immediate acquisition test/check] Class. “Granite is an igneous rock consisting of the minerals quartz, feldspar, and mica.” Teacher. “Excellent saying that definition with so much enthusiasm.” Now the teacher firms up background knowledge of minerals that are the DEFINING features of granite, before she presents examples that contain the minerals and nonexamples that do not. Teacher. “We have already studied the minerals quartz, mica, and feldspar. Let’s review them before we go on….” [Now the teacher shows examples of each mineral and asks students to identify them. Structure (flakes, crystalline, what defines each mineral. When students are firm on this—that define and identify examples and nonexamples of each flat planes) is is, when they correctly mineral---the teacher moves to the next step.] Teaching the new concept, building on background knowledge First the teacher shows examples of granite that differ in NONessential ways (e.g., color and shape) but are the same in the defining features. Logic: Comparison to identify sameness. Teacher. “Now, I’ll show you how to use the definition of granite, and your knowledge of what mica, quartz, and feldspar look like, to identify rock samples.” [The teacher holds up or shows slides of granite, and names each one as granite. The examples differ in size, shape, and color of minerals; e.g., pink and quartz. But they share the essential and defining features—the structure grey of quartz, mica, and feldspar.] Teacher: “This is granite…Notice the mica (black flakes), feldspar (white with flat planes), and quartz (pink and crystalline).” Quartz [Crystalline] Mica [Black] Teacher. Feldspar [Flat planes] “And this is granite… Quartz is orange and crystalline, feldspar is whitish with flat planes, and mica is black flakes. There are different colors than in the first example, but they all have the structure of mica, feldspar, and quartz.” Mica Feldspar Quartz Teacher. “And this is granite… Quartz is green and crystalline, feldspar is yellow with flat planes, and mica is black flakes. There are different colors than in the last example, but they all have the structure of mica, feldspar, and quartz.” Mica Feldspar Teacher. Quartz “And this is granite… Quartz is pink and crystalline, feldspar is grey with flat planes, and mica is black flakes. There are different colors than in the last example, but they all have the structure of mica, feldspar, and quartz.” Quartz Mica Feldspar Notice that the WORDING is the same each time! Next the teacher juxtaposes (puts next to each other) examples of granite and not granite, and labels them. Examples and nonexamples are similar in NONessential features (e.g., color and shape) but are different in that examples have the defining features and nonexamples do not. Logic: Contrast to identify the differences that make the difference. Teacher. “This is granite. Notice the mica, feldspar, and quartz….” Granite Teacher. “This is not granite. Notice that it has no quartz. So it can’t be granite.” Not granite Teacher. “This is granite… Again, see the mica, quartz, and feldspar.” Teacher. “But this is NOT granite. It is chunky, like the last example of granite, but there is no quartz or feldspar. So it can’t be granite.” 4. Closing Reread the objective above. The teacher has completed the focused instruction portion. Now the teacher gives an acquisition test/check to see if instruction was effective; that is, to see if students achieved the objective. So---just as the objectives states---the teacher presents examples of granite and nongranite; asks students to identify them; and asks students to justify their answer, using the definition of granite. Teacher. “Everyone. Is this granite?” Class. “ Yes.” Teacher. “How do you know?” Class. “There is mica, feldspar, and quartz.” Teacher. “Yes, it is granite. Good use of the definition to explain your answer.” Teacher. “And is this granite?” Class. “No.” Teacher. “How do you know?” Class. “There is no quartz.” Teacher. “Correct! No quartz. So, it cannot be granite. .” The teacher repeats the test with several more examples and nonexamples. The teacher corrects any errors. For example, if a student says “Granite,” but the sample is NOT granite, the teacher uses the model, lead, test (or just model and test) correction procedure. Teacher. “This is NOT granite. Granite consists of three minerals: mica, quartz, and feldspar. [Model] Does this sample have mica, quartz, and feldspar?” Student. “It has mica and feldspar, but no quartz.” Teacher. “So can it be granite?” Student. “No.” Teacher. “How do you know?” Student. “It has to have quartz, too.” Teacher. “Correct. It does not have quartz. So it can’t be granite.”